Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

When Sennacherib of Assyria (704–681 BC) inherited the throne of his father, Sargon II, the ancient world thought they were in for a season of relief from Assyrian heavy-handedness. Numerous surrounding territories began making plans for revolt. As it turns out, this was a significant mistake. Sennacherib stormed south into Babylonia, capturing the kingdom and its allies, before turning to the west to tamp down revolts in Philistia and Phoenicia. King Hezekiah of Judah, warned by the prophet Isaiah against joining in this rebellion, had a decision to make.

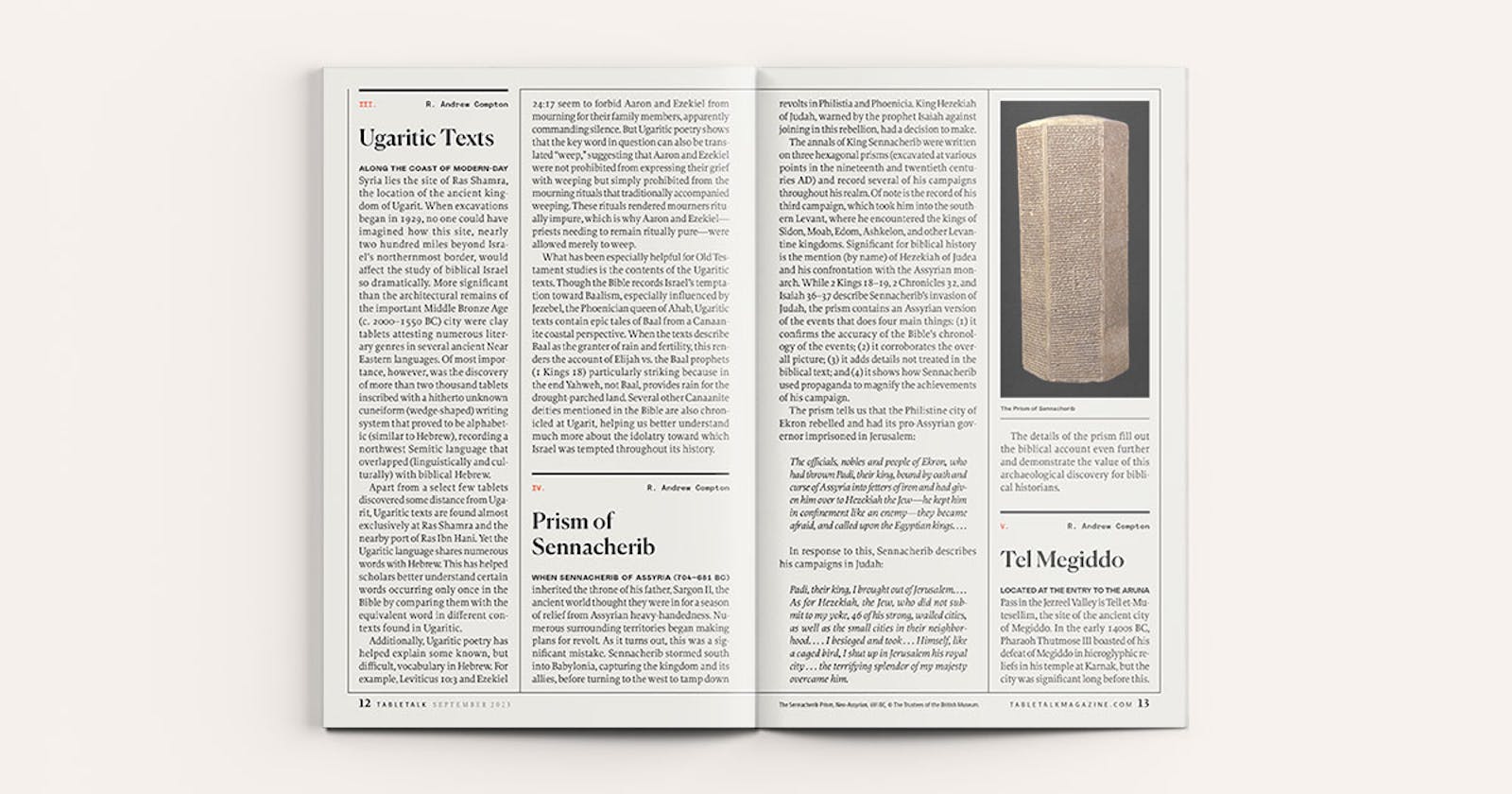

The annals of King Sennacherib were written on three hexagonal prisms (excavated at various points in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries AD) and record several of his campaigns throughout his realm. Of note is the record of his third campaign, which took him into the southern Levant, where he encountered the kings of Sidon, Moab, Edom, Ashkelon, and other Levantine kingdoms. Significant for biblical history is the mention (by name) of Hezekiah of Judea and his confrontation with the Assyrian monarch. While 2 Kings 18–19, 2 Chronicles 32, and Isaiah 36–37 describe Sennacherib’s invasion of Judah, the prism contains an Assyrian version of the events that does four main things: (1) it confirms the accuracy of the Bible’s chronology of the events; (2) it corroborates the overall picture; (3) it adds details not treated in the biblical text; and (4) it shows how Sennacherib used propaganda to magnify the achievements of his campaign.

The prism tells us that the Philistine city of Ekron rebelled and had its pro-Assyrian governor imprisoned in Jerusalem:

The officials, nobles and people of Ekron, who had thrown Padi, their king, bound by oath and curse of Assyria into fetters of iron and had given him over to Hezekiah the Jew—he kept him in confinement like an enemy—they became afraid, and called upon the Egyptian kings. . . .

In response to this, Sennacherib describes his campaigns in Judah:

Padi, their king, I brought out of Jerusalem. . . . As for Hezekiah, the Jew, who did not submit to my yoke, 46 of his strong, walled cities, as well as the small cities in their neighborhood. . . . I besieged and took . . . Himself, like a caged bird, I shut up in Jerusalem his royal city . . . the terrifying splendor of my majesty overcame him.

The details of the prism fill out the biblical account even further and demonstrate the value of this archaeological discovery for biblical historians.