Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

The major rap against Calvinism is contained in the ceaseless mantra that it undermines the church’s mission of evangelism. After all, if John Calvin’s understanding of predestination is true, then there is no urgency to the evangelistic task. Why bother with vigorous outreach if the number of the elect was settled in eternity and nothing we do or don’t do can change the immutable decrees of God?

The response to this criticism is threefold. In the first instance, the reply is Biblical exegesis. The second is the response of historic theology. The third is the testimony of history.

With respect to the first reply, we note that the doctrine of election is not the invention of Calvin—or of Martin Luther, or even of Augustine. It is the teaching of Scripture, to which the aforementioned greats of the church were simply being faithful.

Election is taught throughout Scripture, but most clearly in the teaching of the church’s premier theologian, the apostle Paul. Nowhere is Paul clearer in his proclamation of election than in the ninth chapter of Romans. But Paul also penned the 10th chapter of Romans. There he writes:

“For there is no distinction between Jew and Greek, for the same Lord over all is rich to all who call upon Him. For ‘whoever calls on the name of the Lord shall be saved.’ How then shall they call on Him in whom they have not believed? And how shall they believe in Him of whom they have not heard? And how shall they hear without a preacher? And how shall they preach unless they are sent? As it is written: ‘How beautiful are the feet of those who preach the gospel of peace, who bring glad tidings of good things!'” (Rom. 10:12–15).

Here Paul gives a list of sequential rhetorical questions, questions that can be answered only in the negative. The tacit answer to each question is obvious: “They can’t.” So it goes: How can they call upon Him in whom they have not believed? They can’t. How can they believe in Him of whom they have not heard? They can’t. How can they hear without a preacher? They can’t. How can they preach if they are not sent? They can’t.

These questions, with their clearly implied answers, consistently express the apostle’s understanding of the way of salvation, the way in which the eternal purposes of God are carried out in time and space. Paul elsewhere makes it clear that God not only chooses whom He will save but also by what means they shall come to salvation. God not only chooses people, He chooses a method to reach those people. He has chosen the foolishness of preaching as that means. He has purposed that it should be by the power of the Gospel, which is the power of God unto salvation (Rom. 1:16).

Election is not an abstract notion that is not worked out in the reality of history. The elect are saved by faith, by believing in the Gospel preached unto them and heard by them. They respond not in the flesh but in the power of the Holy Spirit working on them and within them.

In theological terms, we make a distinction between ends and means to those ends. With respect to God’s sovereignty in election, we understand that He sovereignly decrees not only the ends but also the means to those ends. It is God’s sovereign command of evangelism that is His appointed means to the ends He has decreed.

At the heart of the doctrines of grace stands the doctrine of God’s sovereignty. What gross folly it would be for a Calvinist to declare that he believes that God is sovereign in His decree of election (the end) but not sovereign in His decree of evangelism (the means). If we had no other reason to evangelize than that a sovereign God commands that we be engaged in evangelism, that reason would be sufficient to bind our consciences absolutely and to impose a holy obligation upon the entire church. Any person who claimed to be a Calvinist while eschewing evangelism would reveal that he is not only not a Calvinist but is guilty of slandering the very Calvinism he claims to embrace.

Thus, in the first instance, we evangelize because we are commanded to do so. But obedience to the divine command is not our only motive for evangelism. Far beyond being a duty and responsibility, evangelism is also an unspeakable privilege and opportunity.

In Romans 10:15, Paul cites this statement of the prophet Isaiah: “How beautiful are the feet of those who preach the gospel of peace, who bring glad tidings of good things!” Here, the feet of those who carry the treasure of the Gospel are called “beautiful.” The human agents to whom God entrusts the power of the Gospel are honored by their participation in God’s saving plan of redemption.

No preacher, no evangelist, no human being has the power to bring forth the fruit of the Gospel. The power is not in the preacher but in God, who empowers the Gospel for fruit. I can plant or I can water, but only God can bring the increase. Yet planting and watering are great privileges delegated to us by God. He could carry out these activities without us. But He has chosen to include us in the holy drama of redemption.

Finally, the testimony of history to Calvinism does not reveal evangelistic inertia but rather evangelistic boldness and aggression. We recall the Reformation as the greatest awakening in the history of Christendom. This awakening was driven by the human agency of men sold out to the doctrine of election, including Luther, Calvin, and John Knox.

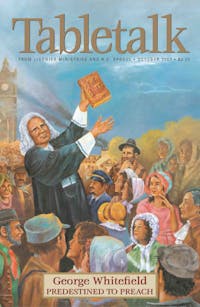

Likewise, the greatest revival in American history, the Great Awakening, was led chiefly by three preachers. The three men God used most powerfully in this evangelistic endeavor were John Wesley, Jonathan Edwards, and George Whitefield. Two of these men were fully committed to Calvinistic theology (Edwards and Whitefield), while the third (Wesley), while not embracing the doctrines of grace, came out of a church communion whose confession of faith was Calvinistic. Whitefield’s passion for souls was matched by his passion for the doctrines of grace.

In our own time, we see an ongoing accent on evangelism among Reformed churches and ministries. For instance, the only ministry that I know of that is currently operating in every single nation on planet earth is Evangelism Explosion, a ministry founded by a convinced Calvinist. In the seminary where I teach (Knox Theological Seminary), every member of the faculty is required to be engaged in evangelism on a regular basis. In this respect, we are not only heirs of Knox and the Reformation, but of George Whitefield, as well.