Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

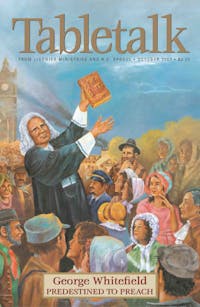

Great crowds, international fame, best-selling books, intense media attention, sniping critics, and simmering concerns among orthodox pastors all swirling around the arrival and work of a great and famous traveling preacher—these phenomena are well-known to us today, but they also marked the ministry of the Anglican missionary evangelist George Whitefield (1714–1770).

Whitefield was the greatest, most remarkable, and most active preacher of his day, preaching often to as many as twenty thousand souls at a time and to millions through his career, without the aid of modern technology. But reaction to his ministry was mixed. Some resented his fame and message. Others who believed the Bible, loved the Lord, and confessed the historic Reformed confessions and practice supported much of Whitefield’s theology, but yet were concerned about his methods, his itinerant preaching, and his use of colorful, emotive language and even a sort of drama in the pulpit.

Preparation for His Mission

He was born to a family in decline. His father died when George was young, and his step-father abandoned the family. Young George was not a great student, but he loved drama and grand stories.

His turn toward evangelical religion began after his admission to Pembroke College, Oxford. Whitefield worked his way through university by waiting on his fellow students. He was lonely, but he found comfort and fellowship with Charles Wesley in a small Bible study group. Whitefield made a determined effort to earn favor with God through fasting, private devotions, attendance at worship, and small-group meetings, but his studies suffered and he worked himself nearly to the point of collapse. Taking a leave of absence from Oxford, he returned to Gloucester and Bristol, where he worked with the poor and prisoners. It was there that he began to understand the nature of grace, that he could not earn God’s favor, but that it is received through resting in the finished work of Christ.

Returning to Pembroke, he finished his undergraduate studies in the spring of 1736 and began a vigorous and remarkable preaching ministry in London as a deacon in the Church of England. In a very short time, at a very young age, Whitefield became the most popular and most widely heard and published preacher in London, but he would not take a permanent pulpit. He and others had letters telling of adventures in the American Colony of Georgia, so Whitefield spent much of his energy preparing for a trip to the New World and collecting funds for the support of an orphanage to be built there.

His Mission to the New World

In Georgia, he adapted his ministry by going house to house catechizing, praying with, and exhorting families. Where the Wesleys had met mostly with failure, Whitefield encouraged the formation of churches and schools, and laid the foundation for the orphanage, Bethesda, which he would begin building on his second trip in 1740 and which would become his base for future operations.

In 1737, upon returning to England, Whitefield was ordained to the office of “priest” in the Anglican communion. His parish was to be much of Britain and the American Colonies. But unlike during his first stint in London, this time he encountered resistance, even closed pulpits, sometimes because of his Reformed theology, sometimes because of his methods. Therefore, according to Charles Hodge, Whitefield took the opportunity to become an open-air preacher, a controversial move that was regarded by many critics as a sign of his radicalism. However, despite his lack of a settled congregation and the support of the established ministers in London, Whitefield’s open-air preaching drew large crowds. One Hyde Park sermon drew as many as eighty thousand hearers. Over one summer of relentless preaching, nearly a million souls heard him proclaim Christ.

He returned to the Colonies in the autumn of 1739 as a famous preacher. By November, he was preaching open-air Gospel sermons in Philadelphia to great crowds and success, setting a pattern in North America of transdenominational mass evangelism that has been adopted and adapted by evangelicals ever since.

However, the reactions that had greeted Whitefield in London were repeated in the New World. Some supported him, while others opposed him as a “sheep stealer.” Local pastors complained of having to compete with a professionally produced, traveling production. More than once, Whitefield’s outdoor sermon was followed by a parish pastor denouncing him, either because of his methods, his Calvinism, or both. Whitefield, however, did not preach open-air sermons on Sunday mornings, and he always attended services. He did not view himself as a competitor to local preachers.

By this time, the preaching of Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758) had ignited the First Great Awakening in Connecticut, and with it controversy over theology and practice. But the supporters of the awakening were as vociferous as the critics. For instance, the Presbyterian Gilbert Tennent (1703–1765), in his notorious 1740 sermon, “The Danger of an Unconverted Ministry,” attacked critics of the awakening as unconverted “Pharisees.” Whitefield himself warned about unregenerate ministers in the Anglican church and alleged that the late archbishop of Canterbury, John Tillotson (1630–1694), had not experienced “the new birth.” (Some of the anti-revival critics were indeed rationalists, such as the Congregationalist minister Charles Chauncy [1705–1787], but others, such as the Presbyterian “Old Side” minister John Thomson [c. 1690–1753], were sincere, devout, and orthodox men who wanted to see ministry and evangelism centered in the church.)

Whitefield also encountered opposition within the revival movement over the nature of divine grace. In 1739, John Wesley attacked Whitefield’s doctrine of predestination. In 1740, Whitefield responded by defending the Reformed view. Their friendship was strained, but not destroyed. The “methodist” movement, however, was divided between predestinarians and Arminians.

Through the 1740s, Whitefield’s preaching faced increasing opposition in London, not only from angry Anglicans, but from local businessmen who lost money because of him. Violence—he was beaten with a cane in 1744 and attacked by a Dublin mob throwing rocks in 1751—and threats of violence increased, and his exhausting scheduled taxed his health. When he returned to America, he found a backlash there, too.

Tennent eventually repented of his claim that his opponents were Pharisees, and Whitefield published several apologies, including one to Harvard College in January 1745, for his sometimes intemperate language against his critics. In turn, newspapers published public endorsements of Whitefield’s character, including one by Benjamin Franklin.

Despite failing health, Whitefield traveled widely through the Colonies, preaching frequently to enthusiastic crowds. Fittingly, his last sermon was in the fields, in Massachusetts, with the preacher having worn himself to absolute exhaustion. His topic was justification and the insufficiency of works for righteousness before God. Warming to his theme, he began to roar: “Works, works! a man gets to heaven by works! I would as soon think of climbing to the moon on a rope of sand.” By 5 a.m. on Sunday, Sept. 30, 1770, he was struggling to breathe, worried that he would not be able to preach that morning. He did not make it to the pulpit again. An hour later he was dead. The following Tuesday, six thousand mourners gathered for his funeral, after which he was buried in the Presbyterian Church at Newburyport, Mass.

Implications of His Mission

Whitefield was a pioneer in the modern methods of mass evangelism. Though his preaching was largely extemporaneous, the same was not true of his meetings. They were carefully planned, advertised, and even timed to coincide with popular events. He was not above using tension with local clergy to create interest in the meetings. He often brought his own core of “methodist” supporters, and they learned how to build a crowd, as well as suspense and excitement. Whitefield learned the power of a well-timed, plainly spoken extemporaneous prayer and a sermon with clear, colorful, popular, even homely illustrations and pointed language. In themselves, of course, such practices are not necessarily harmful, but neither were they without consequences.

There can be little doubt that God was with Whitefield’s preaching ministry and that, in many ways, he offered a refreshing message of the undeserved sovereign, electing, and justifying grace of God to sinners in Christ Jesus. For those committed to the solas of the Reformation, Whitefield’s theology should be seen as an eighteenth-century heir of Luther and Calvin.