Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

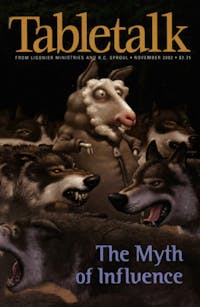

I recently returned from teaching in a Third World country. It is, in many ways, typical. There is growing starvation, a massive epidemic of AIDS, an equally massive epidemic of governmental corruption, ethnic conflicts, and great political uncertainty. Bibles are few, the church is poor, and it has few trained pastors. Yet I ministered to people who were hungry for the Word of God. Whenever I spoke, I was followed by eager and earnest attention.

By contrast, here in America, where I work, we have more Bibles than we know what to do with, churches in abundance, religious institutions, religious presses, political stability, more food than we can eat, and the world’s best medical care. And yet, our appetite for the Word of God, for His truth, is tepid. The Africans among whom I worked are poor in the things of this world, but, I suspect, they are rich toward God. We are rich in the things of this world, but am I wrong in thinking that we are poor in the things that really matter?

What has gone wrong? Let me try to put my finger on one aspect of this problem.

In two national surveys this year, George Barna explored the question of whether people believe that moral truth is unchanging or whether circumstances should be taken into consideration in deciding what is right. In the nation as a whole, only 22 percent thought there are moral absolutes that should remain unchanged by circumstances, while 64 percent opted for relativism. The findings were even more dramatic among teenagers, among whom 83 percent opted for relativism and only 6 percent opposed it. And among those who claimed spiritual rebirth, only 32 percent of adults expressed belief in moral absolutes, and the figure for teenagers was only 9 percent. Barna’s conclusion is that with such overwhelming capitulation to relativism, the church is in deep trouble.

It would be quite reasonable to suppose that grasping this fact might lead to some rethinking. Where have we gone wrong? How can we recover what we have lost? If Christianity is not about truth, both by way of belief and moral behavior, what does it have to offer? Can it survive?

These, however, are not the questions that Barna and those like him are asking. “Continuing to preach more sermons,” he reasons, “teach more Sunday school classes, and enroll more people in Bible study groups won’t solve the problem since most of these people don’t accept the basis of the principles being taught in those venues.” This may be true as long as the worldview of those in the church is left unchallenged. But can the church be the church if it is not summoned by the Word of God, addressed by the Word of God, and rebuked and nourished by the Word of God? The disappearance of truth from the church, driven out by a loss of appetite for it and an unwillingness to take it seriously, really does put the church in jeopardy.

This loss of truth has not happened overnight. It is the result, I believe, of three main developments: the intrusion of the postmodern ethos; the unraveling of the post-war evangelical coalition; and the attempt to redefine the church in terms of consumption.

THE POSTMODERN WORLD

Since the 1960s, America has undergone a stunning transformation in cultural mood. Prior to this time, at both ends of the cultural scale—high and popular—the dogmas of the Enlightenment were deeply ensconced. It was simply assumed that God was irrelevant to life, that we could find for ourselves what His revelation had once provided, and that all morality and meaning was found within. Initially this was discovered in the mind, but then, as psychology took hold, people searched in the self. The place God once occupied in life was now taken by the human being in the Enlightenment cultures of the West.

It is difficult to say exactly why this view of life suddenly lost credibility and then collapsed like a house of cards after the 1960s—in the academy, in movies, even in the workplace. But it did. It was replaced by a mood that is skeptical of all meaning that is universal and of anyone’s ability to find truth, since none of us can escape our own subjectivity and the lenses through which we see things.

Among Europeans, this has produced a deep, brooding nihilism, the belief that there is nothing “out there” that can be known, that we are alone in a universe empty of meaning, that words and texts mean what the reader, not the author, says they mean. In America, it has produced a similar emptiness, but this is often concealed behind the typical American can-do spirit and its obsessive consumption. This mood was brilliantly captured in the 1990s television series Seinfeld, which by its own reckoning was a show about nothing, but which explored the comic consequences of living in a world that is empty of truth or meaning.

When this mood enters the church, inadvertent and unnoticed as it might be, it brings with it a thoroughly this-worldly preoccupation that is often focused therapeutically, and a skepticism about the importance of God’s revealed truth. Pastor Alan Nelson, who passed up seminary training for a degree in psychology and now leads a seeker-sensitive megachurch in Arizona, betrays his real worldview when he says that the “typically educated person will walk into church and say: ‘Who listens to pipe organs? And who does chants and listens to messages that have to do with some doctrinal issue when I am living 24/7 with marriage and stress?’ ” Apparently, he has concluded that biblical truth is neither of interest nor of use to harried postmoderns.

THE COLLAPSE OF EVANGELICALISM

The emergence of the evangelical coalition in America after World War II was one of the three most important religious events of the twentieth century, Martin Marty judges, the other two being the growth of the Pentecostal movement from humble beginnings at the century’s beginning into a worldwide, burgeoning movement by the century’s end, and the consequences of the changed immigration laws of 1965, which turned America into the most religiously diverse nation in the world. Of these three, it is the first that appears to be in the late evening of dissolution as this new century begins.

Perhaps this evangelical coalition was an improbable undertaking in the first place, and yet, at the time, it seemed wise and strategically prudent. This coalition, made up of the whole, broad swath of evangelical traditions and denominations, initially worked remarkably well for one simple reason:

There was consensus about its core doctrinal commitments as well as many issues of practice. And part of this consensus concerned the centrality, authority, indispensability, and, in many ways, the practice of biblical truth in the contemporary world.

What allowed for the remarkable success that followed this accord and the coalition around it also became its Achilles heel. This was an informally-agreed-upon doctrinal core, initially assented to by everyone. But like all voluntary accords, there was no mechanism to keep it in place or to protect it. Unfortunately, under cultural and academic pressures, it has begun to fall apart.

For example, Clark Pinnock’s The Openness of God: A Biblical Challenge to the Traditional Understanding of God, argues that God neither sees the future nor can control it. The appeal of this modification in orthodox belief is that if God does not know what decisions we are going to make, then we are truly free to do what we want. If He knew in advance what we would decide, we would not be free to change our minds at the last moment because His knowledge cannot be invalidated. More recently, Joel Green and Mark Baker, in Recovering the Scandal of the Cross, have contended vigorously against the idea of penal substitution in Christ’s death, and with that they have attempted to dislodge the doctrine of justification from the apostolic gospel, at the same time mutilating the doctrine of propitiation. These books are coming out of the heart of the evangelical world, where, quite clearly, the center is not holding and things are falling apart.

What has been happening in academia is being duplicated in church life all over the evangelical world. The consensus that was once there about the centrality of the truth of Scripture to the church’s understanding of God and the world, its place in nourishing, correcting, and building up the people of God, is gone. Lip service is paid to its inspiration, but, in practice, what is served up in too many churches is not serious biblical exposition but inspirational stories, amusement, and psychological pablum.

SELLING THE FAITH

If the mood in our culture has been drastically transformed since the 1960s, so has our understanding of how the church should be relating to that culture. Driven by a deepened sense of cultural change, as well as by the fact that since 1976 the evangelical world has stopped growing, multiple experiments in how to “do church” differently and more successfully have been undertaken. What most of them have in common is the assumption that the church needs to think of itself as a business. It needs to pitch itself to the marketplace. It needs to think of Christianity as a “product” and sinners as “consumers.” The analogy is entirely fallacious, of course, because Christianity is not a product that we can own; the God of the gospel is the One who owns us. We cannot negotiate its price; its price is our complete surrender. Nevertheless, this understanding is driving many churches to see themselves as service organizations, laying out a rich choice of products from which consumers can pick and choose: multiple forms of worship for all tastes and different kinds of “sermons,” from casual talks to amusing skits.

In the next stage in this development, some churches are now offering an even wider variety of benefits in order to attract potential consumers. Many, of course, serve the obligatory Starbucks coffee; some have fast-food outlets on their premises, and others food courts. In some churches, there are legal offices, travel agencies, beauty parlors, schools, and day-care centers. Some offer lessons in karate, while many have fully equipped gymnasiums and saunas. Many provide a smorgasbord of self-improvement programs, courses in career advancement, and opportunities for counseling of all kinds. The larger these churches become, the more they are able to duplicate the outside world. In so doing, they can become an alternative to that world. Wade Clark Roof has spoken of them as safe, secure “gated communities” for the spiritual. And this brings us to a striking irony: These churches may have set out to win the world, but they are ending up disengaging from it.

There certainly is nothing wrong with Christians seeking financial counsel, taking voice lessons, making travel arrangements, or wanting to go to the theater. However, in using these devices to sell the church—devices that in themselves have nothing to do with worship, biblical knowledge, and growing in the understanding of God—we are placing a premium on attracting a crowd and forgetting that the point of it all should be an encounter with the truth of God’s Word and with the God of that truth. These churches are tremendous success stories, but what their success tells us is that it is quite possible to do well with very little truth. In the next generation, the consequences of this are going to be painful.

We would do well to ponder the fate of the churches to whom John wrote in the book of Revelation. These were actual churches, though they also serve the purpose of representing the church universal. Christ commends them for what needs to be commended (Rev. 2:2–3, 6, 9–10, 13, 19; 3:4, 8). He exposes their unfaithfulness (Rev. 2:4, 14–15, 20; 3:1–2, 15–18). He warns them to repent where repentance is needed (Rev. 2:5, 16, 21–23; 3:3, 15–18). And to each He gives a special promise (2:7, 11, 17, 26–29; 3:5–6, 12–13, 21–22). Within the space of a very short period of time, however, all of these churches simply disappeared. The lampstand was removed from its place (Rev. 2:5). That should not be forgotten.