Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

Latent optimism is deeply embedded in the psyches of most American evangelicals, reflecting the apparently indelible optimism of the American character. Whatever formal eschatology American evangelicals hold, most are still optimistic about the future of their nation and of the church within it. They see a nearly messianic role for America in contemporary world history.

Given their character and historical interests, American evangelicals tend to expect to be influential in the world in which they live. They believe they should—and can—make a difference. Therefore, they continue to organize and contribute to many causes that they hope will improve their nation, supporting a great variety of missionary, educational, political, and philanthropic activities. They may well be the most active and generous people in the history of the church.

The desire to be a good influence is certainly praiseworthy. Historically, Christians have been a positive influence in many ways and in many fields. They certainly should continue in every responsible way to exercise an influence for good in the world.

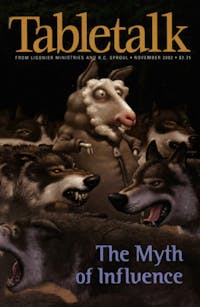

Are there, however, dangers that may accompany the desire to be an influence? Are there pitfalls that Christians need to avoid on the road to influence? The greatest danger for Christians in our time is to seek influence through improper compromise.

For some Christians, the very word compromise is a bad one. But that should not be the case. Compromise is often a very proper and useful solution to a difficult situation. In politics, for example, we frequently see that compromise is a path to action and progress.

Sometimes a refusal to compromise is just stubbornness or small-mindedness. When we consider the conflicts in the Middle East, the Balkans, or Northern Ireland, we often ask, “Why can’t everyone just give a little?” And yet, Christians themselves are often unwilling to compromise in the culture wars.

Of course, compromise can be an absolute betrayal of Christ. Many advised Athanasius that he ought to compromise on Nicea’s confession that the Son was of the same substance with the Father. They argued that unity and peace would be served if he just would compromise and confess that the Son was of a similar substance with the Father. Likewise, Martin Luther was advised at Worms to compromise on his insistence that we are justified by grace alone through faith alone. Both men refused to compromise. Later, Luther would say, “Let us have peace if possible, but truth in any case.”

The pressure to compromise for the sake of cooperation and greater influence sometimes rests on the relativism so prevalent in our time. We hear the call: “Don’t be so dogmatic. What makes you so sure? That may be right for you, but you can’t believe it’s right for everyone.” The claim to know objective truth that is true for everyone strikes many today as intolerant and bigoted.

Christians must reject any call to compromise that relativizes the absolute claims of Jesus: “I am the way, the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through Me” (John 14:6). No opportunity for influence can be won by equivocating at this point. Indeed, where such equivocating takes place, the Christian is not influencing the world—he has been influenced by the world.

I am not calling for Christians to be obnoxious, unfriendly, or sectarian. Neither am I arguing that all theological points are of equal importance. I am suggesting that sound theology must be the foundation of all Christian action. The great Christians in history who made a real impact on their world stood unwaveringly and without compromise on the essentials of the gospel.

Consider the example of Abraham Kuyper, who was featured in last month’s Tabletalk. Kuyper grew up in the home of a Reformed pastor in the middle of the nineteenth century. The influence of strong, orthodox Calvinism in the Netherlands had declined greatly. The orthodoxy of the churches had softened or disappeared, and the believers who remained orthodox had little influence. But after his own conversion, Kuyper came to appreciate the intellectual integrity and spiritual power of true Calvinism. He went on to become the most influential reformer that Calvinism has seen in modern times.

As a pastor, Kuyper reformed the church, returning it to confessional theology and Reformed polity. As an editor, he produced journals that supplied both devotional and in-depth studies to encourage and lead Reformed people. As an educator, he established and supported schools to advance the cause of Calvinism. As a politician, he reorganized his political party and led it to a victory that made him prime minister. As a thinker, he retooled Reformed Christianity through his distinctive Calvinistic worldview.

In his worldview, Kuyper did not long to re-establish medieval Christendom, in which church and state cooperated to enforce a version of Christian civilization. But neither did he accept the modern notion that religion should be only a private, personal matter. He believed that Christians should have a vision and a witness of how to serve God in every sphere of life, and he taught that Christians need to understand and articulate that vision for themselves out of the Scriptures. Here they must not compromise. Kuyper saw the wisdom of the motto of his political party, “In our isolation is our strength.” Christians take their vision of the true and the good not from the world but from Christ.

Kuyper also recognized, however, that once we have our vision and goals clearly set, then a measure of cooperation with others is possible. For instance, he joined with the Roman Catholic political party to pursue the political goal of using tax money to fund religious schools. He believed that Reformed parents ought to build Calvinistic schools for their children and that the state ought to return tax money to them for that purpose. But he also believed that the state ought not to oppress other parents in the exercise of their religion, so he asserted that Roman Catholic and Jewish parents also ought to have state help in building schools for their children. Because Kuyper’s vision was so clear and strong, founded on his orthodox Calvinist convictions, he could cooperate without compromise with other parties and other faiths for specific goals.

We need modern Kuypers today, Christians who are both thinkers and activists for the cause of Christ. They must not be beguiled by the relativism or temptations to ungodly compromise of our time. They must not be deceived by a mirage of influence that really changes them. They must beware of a naïve optimism that promises constant success in this world. Rather, Christians should try to be godly influences wherever they can. Let us seek to sow the seed of God’s truth, knowing that the increase ultimately rests only with Him.