Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

In the book of Leviticus, we read God’s mandate to His people:

For I am the Lord your God. You shall therefore consecrate yourselves, and you shall be holy; for I am holy. Neither shall you defile yourselves with any creeping thing that creeps on the earth. For I am the Lord who brings you up out of the land of Egypt, to be your God. You shall therefore be holy, for I am holy. (Lev. 11:44–45)

In Creation, man was made in the image of God. Part of the significance of this truth is that, being stamped with the divine image, human beings are called to reflect the character of God.

When God formed Israel as a nation unto Himself, He called the people to holiness, a kind of moral “otherness” or “apartheid.” God’s people were to be different, to be consecrated or “set apart.” They were to be unlike other nations and peoples. And the difference was to be seen in their loyalty and obedience to God.

In one sense, the Old Testament record is the history of Israel’s failure to obey this mandate. The people’s covenant infidelity was marked by a desire to be like other nations, to abandon the uniqueness to which they were called. Instead of being a light to the gentiles, they were enticed to embrace the darkness of the world around them. This was seen in the people’s clamoring to Samuel for a king. Despite both the warning of Samuel and of God Himself, the people persisted:

“Nevertheless the people refused to obey the voice of Samuel; and they said, ‘No, but we will have a king over us, that we also may be like all the nations, and that our king may judge us and go out before us and fight our battles’ ” (1 Sam. 8:19–20).

Several years ago, I read an analysis of the development of children written from a psychological perspective. The author argued that from birth to age 5, the most important influence in the life of a child is the mother. From 6 to 12, the most powerful influence is the father. Then, from 13 to 20, the most significant influence is the person’s peer group. Adolescence is seen as the period of highest pressure to conform to one’s immediate culture.

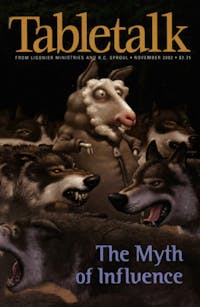

I don’t know how accurate this analysis is, but it certainly seems to be borne out in the behavioral patterns of adolescents. For the teenager, it is often a fate worse than death to be considered “out of it.” To be “with it” is a powerful seductive force that, sadly, does not end at age 20. The desire to be accepted by the mainstream of the culture has been a fierce and destructive force to the people of God in every generation. The tendency to accommodate the faith to the culture did not end with the Old Testament.

We have seen countless examples of universities, colleges, and seminaries chartered with a strong commitment to orthodox Christianity, only to erode first into liberalism and ultimately into secularism. Why does this happen? There are multiple, complex reasons for the apostasy of such institutions, but one key factor is the desire of professors to be intellectually recognized in the academic world. A slavish genuflection to the latest trends in academia seduces our leaders into conformity. One apologist once described this pattern as the “treason of the intellectuals.” If the secular establishment ridicules such tenets as the inspiration of the Bible, then insecure Christian professors, desperate to be accepted by their peers, quickly flee from orthodoxy, dragging the colleges, seminaries, and ultimately the churches with them. It is a weighty price to pay for academic recognition.

In the second half of the twentieth century, the church witnessed the steady decline of historic evangelicalism to such a degree that the term is now hardly recognizable. The church lost what Francis A. Schaeffer called the “antithesis” between a Christian worldview and secularism. The result is that it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between left-wing evangelicalism and liberalism with respect to methodology, theology, and ethics.

The justification for this erosion among evangelicals is the goal of influencing the world. Martin Luther called for a “profane” Christianity in the literal sense, meaning that the church is called “out of the temple” and into the world. Indeed the world is our mission field, our theater of operations. The difficulty, as always, is to influence the world without surrendering to it. The line is crossed when, in our zeal to reach the world, we accommodate the truth of God to that world.

For a current example of such accommodation, we need look no further than the controversy that is raging with respect to Bible translating. In 1997, it was discovered that a British edition of the New International Version was being produced that included a translators’ explanation that one of the goals of the version was to “correct the patriarchalism” of the Bible. Masculine words such as man, brother, and son, as well as pronouns such as he and him, would be eliminated in favor of “gender-neutral” terms such as people and children. This disclosure evoked a hue and cry resulting in a public pledge by the presidents of the International Bible Society and Zondervan Publishing Co. not to proceed with such a translation. In a cordial atmosphere, these men signed guidelines for translation at a meeting in Colorado Springs, Colo., that year.

But in early 2002, the International Bible Society and Zondervan announced the preparation of Today’s New International Version (TNIV). The day before the announcement was made in the national media, representatives of Zondervan and the International Bible Society notified the signatories of the Colorado Springs accord that they were withdrawing their names from the agreement.

The defenders of the TNIV translation argue that it is driven not by a feminist agenda or by a desire to be “politically correct.” The repeated claims of its authors and publishers is that it is an endeavor to improve the “accuracy” of the English Bible. But if the TNIV is more accurate than the NIV, why does Zondervan intend to continue to publish the NIV? If Zondervan is really committed to accuracy, it would seem that it would have the TNIV replace the NIV altogether.

Actually, the TNIV appears to be a move not toward greater accuracy but away from it. One example: In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus says, “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God” (Matt. 5:9). The TNIV changes sons to children. But the Greek word huios in its plural form means “sons,” not “children.” My Latin Bible translates it “sons” (filii). My German Bible, my Dutch Bible, and my French Bible translate it “sons.” Likewise, every English Bible I own translates it “sons.” Indeed, from the first century until today, the whole world has understood what the Greek says.

It was not until the advent of gender-inclusive language (the legacy of radical feminism and political correctness) that any translation dared to change the original text. This is accommodation to the culture. It cannot be explained by pointing to the fluidity and dynamism of human language. Even today, we still distinguish between male and female offspring by referring to them as sons or daughters. In the scope of Scripture, there is a theological import to the word son that is lost when it is rendered by the term child. The translators may not embrace feminism or political correctness, yet they fall into the trap of accommodating such cultural perspectives.

When a translation moves from the specific to the general (as sons to children), it is not taking a step toward accuracy, but away from it. There is a patriarchal framework to Biblical revelation that is clearly present in the original text. To “change” or “correct” that framework is to take liberties with Scripture that cannot be justified by “dynamic equivalency” or any other methodology.

The task of translation is not to provide a commentary on the original text. The work of interpreting and applying the text to the present culture belongs to pastors, teachers, and students of the Word. When translators undertake this in the name of improved accuracy, they step over a boundary the church has been jealous to guard carefully for two thousand years. Not since Marcion in the second century have we seen attempts to actually change the language of the original text.