Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

Bravery softens. In an essay discussing the means of softening hearts, Montaigne cites Edward the Black Prince’s infamous slaughter of French rebels at Limoges in 1370:

The lamentations of the townsfolk, the women and children left behind to be butchered, crying for mercy and throwing themselves at his feet, did not stop him until eventually, passing ever deeper into the town, he noticed three French noblemen who, alone, with unbelievable bravery, were resisting the thrust of his victorious army. Deference and respect for such remarkable valor first blunted the edge of his anger; then starting with those three he showed mercy on all the other inhabitants of the town.

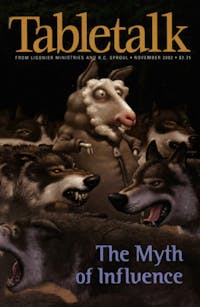

This episode pictures a wonderful aspect of the church’s interaction with an opposing, dominant culture. Because opponents can respect bravery, they can be seduced with bravery; they can be seduced by disrespect. The three French noblemen desperately fighting off Edward’s troops were not trying to gain a place at the table, earn academic respectability, or even be liked. At that moment, they wanted to decapitate and disembowel every Englishman in the arc of their swords, including Edward himself if he would just come close enough. And yet, contrary to all common sense, their bravery, their disrespect, seduced their attacker.

Christ Himself had a reputation like that of these nobles. The Pharisees openly recognized and feared that “You are true, and care about no one; for You do not regard the person of men, but teach the way of God in truth” (Mark 12:14b). Jesus did not care about their opinions. He had a reputation of refusing to kiss up to the cultural elites. In fact, He regularly mocked them. And this brave faithfulness was perceived as “authority,” not bravado—“the people were astonished at His teaching, for He taught them as one having authority, and not as the scribes” (Matt 7:28b–29). Jesus’ disrespect of the surrounding idolatries produced fear and conflict, and ultimately seduced the whole Mediterranean.

And it is no surprise that Christ walked in paths already laid by Elijah (Luke 1:17), for Elijah was one of the premier proponents of conquering via disrespect. He was slandered as the “troubler of Israel” (1 Kings 18:17) even before he publicly humiliated the priests and idols of his day. And what a scene that was: Elijah mocking the most prestigious cultural elites, full of idolatrous seriousness, respectability, and middle-class decency—“Elijah mocked them and said, ‘Cry aloud, for he is a god; either he is meditating, or he is busy, or he is on a journey, or perhaps he is sleeping and must be awakened’ ” (1 Kings 18:27). Elijah proved that the act of mocking arrogance grows out of the fruit of the Spirit, out of true humility.

In our own day, we haven’t even waded into the shallows in mocking modernist arrogance. The biggest opponents to this sort of tactic are most often Christians with deep sentimental streaks who view any ugliness as contrary to the fruit of the Spirit. How many of us would be embarrassed if “weirdos” like Elijah or John the Baptist showed up in our communities saying the sorts of things they said? Evangelicals would be the first ones to pronounce them “troublers of American decency.”

But mocking arrogance—violating the tyrannical decencies of a prevailing idolatry—has to be only part of the battle. We can’t do without it, but it can’t sustain itself either. It’s a glorious, sometimes hilarious, negativity, but it has to ride on a deeper, constructive seduction of truth, beauty, and goodness. We can’t just tear down modernity with bravado and then offer cheap immaturity in its place. Imagine if modernity were to fall, and we were right there to hand people a copy of The Prayer of Jabez or even a theological tome. Those things aren’t life, they’re just pages of words. We have magazines, books, and schools—words, words, words—but no mature communities. No wonder God won’t bless our evangelism. We don’t know how to live any better than modernists.

In the future, when we do learn better, when we do learn that life on earth is not just to growl around longing to escape earth, that the gospel is primarily concerned with living well now (Eccl. 9:7–9), not resenting life, then we’ll truly see the church seduce the world. God promises it: “For this is your wisdom and your understanding in the sight of the peoples who will hear all these statutes, and say, ‘Surely this great nation is a wise and understanding people’ ” (Deut. 4:6). Pagans are supposed to be wowed by our communities, like Sheba was by Solomon: “When the queen of Sheba had seen all the wisdom of Solomon, the house that he had built, the food on his table, the seating of his servants, the service of his waiters and their apparel, his cupbearers, and his entryway by which he went up to the house of the Lord, there was no more spirit in her” (1 Kings 10:4–5). No more spirit in her! What a grand description. That’s what awaits modernity. And she confessed: “Blessed be the Lord, your God, who delighted in you, setting you on the throne of Israel! Because the Lord has loved Israel forever, therefore He made you king, to do justice and righteousness” (1 Kings 10:9).

The church is called to be a holy seductress. We tend to get tripped up in the negative connotations of seduction and leave the notion to the nasty side. But God Himself is the premier seducer: “Do you despise the riches of His goodness, forbearance, and longsuffering, not knowing that the goodness of God leads you to repentance?” (Rom. 2:4). When drawing Israel to Himself, He gave her embroidered cloth, sandals, fine linen, silk, bracelets, necklaces, earrings, and beautiful crowns, and her “fame went out among the nations” because of her beauty, “for it was perfect through My splendor which I had bestowed” upon her (Ezek. 16:10–14).

In our latent gnosticism, we tend to despise the centrality of beauty and goodness in our countercultural battles. We’re so busy boycotting or teaching against pagan worldviews that we have little time actually to create anything ourselves—“always learning and never able to come to the knowledge of the truth” (2 Tim. 3:7)—always teaching, never actually living.

What we really need is a vision that combines the best of Solomon with the best of Elijah—a seductive disrespect that is both negative and positive. The latter is, of course, much more difficult and will take generations. But its glory is that everyone is involved in creating beautiful communities, from the least to the greatest. Different parts of the body create different things, some swinging at the idols, more showing hospitality, creativity, and robust laughter. Then, as the Black Prince of modernity continues to lash out in all his unimaginative pettiness, we’re there fighting nobly, seducing beautifully. And he will marvel at Christ’s church in all her splendor—“And the nations of those who are saved shall walk in its light, and the kings of the earth bring their glory and honor into it” (Rev. 21:24).