Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

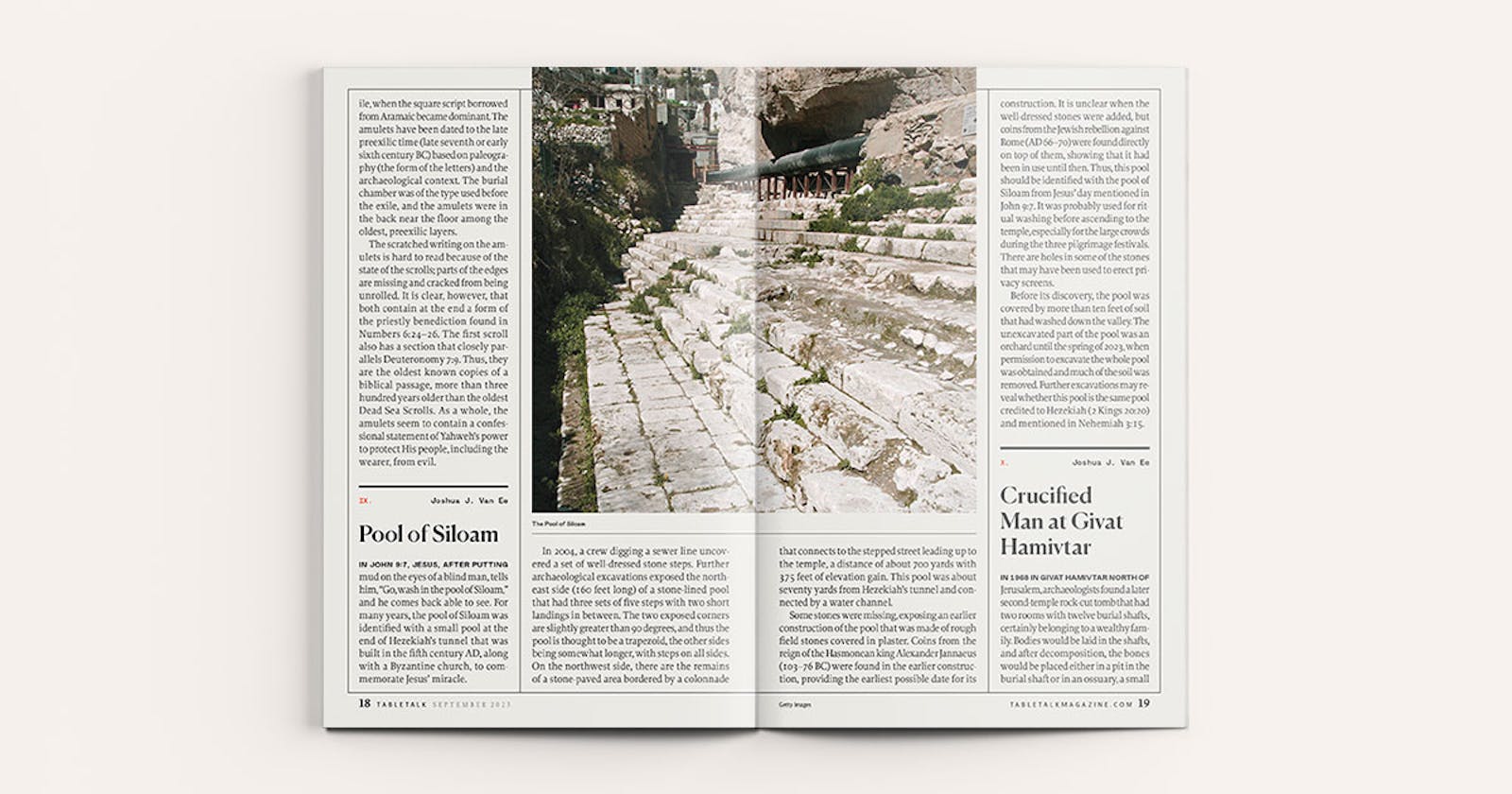

In 1968 in Givat Hamivtar north of Jerusalem, archaeologists found a later second-temple rock-cut tomb that had two rooms with twelve burial shafts, certainly belonging to a wealthy family. Bodies would be laid in the shafts, and after decomposition, the bones would be placed either in a pit in the burial shaft or in an ossuary, a small carved stone box usually made to fit the bones of an individual. Ossuaries were used mainly in the late first century BC and the first century AD, usually by the wealthy, and could be elaborately decorated and have a name etched on the side. There were eight ossuaries in this tomb, and one, about two feet long and one foot wide and tall, was undecorated with the name “Jehohanan son of Ezekiel” (the latter name is debated) on the side. Inside were the bones of an adult male in his mid-twenties, a young child, and at least one bone from another adult. In the right heel bone (calcaneum) of the adult male was a four-and-a-half-inch nail driven from the exterior (lateral) side through the bone. A fragment of an olivewood board was located between the head of the nail and the bone, and the tip of the nail was bent into a curve.

Most scholars identify this nail and bone as the first archaeological evidence of a crucified person (an almost identical find dating to Roman times was discovered in Fenstanton, England, in 2017). Some written sources state that ropes were used to attach a person’s hands and feet for crucifixion, while others, including the New Testament (John 20:25; see Luke 24:39; Col. 2:14), mention nails. This find provides evidence that nails were used and seems to indicate that the man’s feet were nailed to the sides of the upright beam of the cross with a small board on the outside of each foot to keep it from slipping off the nail. Nails were usually removed and reused, but since this one was bent it was left intact. The original analysis argued that the man’s legs had been broken during his crucifixion and that marks indicated that nails had been used on his forearms. A later study has shown this analysis to be unlikely, however. This find provides evidence that someone crucified could be given a proper, even wealthy, burial, as described of Jesus (Matt. 27:57–60; Mark 15:42–46; Luke 23:50–53; John 19:38–42).