Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

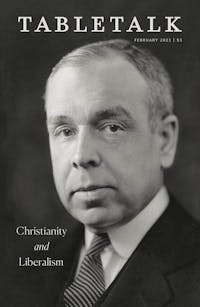

J. Gresham Machen lamented the loss of the conception of God and the consciousness of sin on the modern mind. According to Machen, modern liberalism had, in the first instance, challenged the need even to have a conception or knowledge of God. To inquire after a knowledge of God is the death of religion, it was argued. We ought not to know God but to feel Him; and if we are to conceive of Him, we must do so in vague and general terms. God is Father, but this means nothing more than His universal fatherhood for all creatures, which in turn encourages a universal brotherhood among all peoples.

Machen was, of course, willing to acknowledge that the Scriptures speak in one sense of God’s universal fatherhood (see Acts 17:28; Heb. 12:9). But only a few isolated texts provide support; the predominant understanding of God as Father in the Scriptures is in relation to His redeemed people. For Machen, however, the fatherhood of God was not the center or core of the Christian doctrine of God. Rather, a single attribute “render[s] intelligible all the rest”: the “awful transcendence of God.” Machen was speaking about the awesome holiness of God—His distinctness, His otherness. This, for Machen, was the truth of which modern liberalism had lost sight. As a result, liberalism had erased the Creator-creature distinction that is so fundamental to true Christianity. It had instead produced a pantheistic God who is simply part of the “world process.” God was no longer a distinct being; His life was in our life and our life was in His life. In Machen’s own words:

Modern liberalism, even when it is not consistently pantheistic, is at any rate pantheizing. It tends everywhere to break down the separateness between God and the world, and the sharp distinction between God and man.

A corollary of this (mis)conception of God was a (mis)understanding of man and, in particular, “the loss of the consciousness of sin.” Since God is no longer conceived of as holy and transcendent, He rests lightly on the modern mind, and thus does sin as well. Machen sought to discern the precipitators for this shift in modern thinking. Writing shortly after World War I (1914–18), he believed that war produced an overfocus on the sins of others to the neglect of one’s own sins. In war, where one side is viewed as the embodiment of evil, it is easy not to see the evil in one’s own heart. There was also the problem of the collectivism of the modern state, in which everyone is a victim of circumstances, obscuring “the individual, personal character of guilt.” Behind the shift in the modern doctrine of sin, however, Machen saw a more sinister and significant cause: paganism. By paganism, Machen did not mean barbarianism. During the height of the Greek Empire, paganism was not grotesque but glorious. It was a world-and-life view that found “the highest goal of human existence in the healthy and harmonious and joyous development of existing human faculties.” That is to say, humanity is essentially good and can attain the good, through the proper engagement and discipline of its mind and body. For Machen, such a perspective had become dominant in his day, replacing the Christian view of sin and personal guilt before a holy God.

The result was diametrically opposed views on humanity. “Paganism is optimistic with regard to unaided human nature, whereas Christianity is the religion of the broken heart.” According to Machen, paganism’s problem is that it covers up sin in the heart, and so it looks for a solution from inside the self. Christianity is different: it uncovers sin in the heart, and so looks for a solution outside the self. Paganism divests Christianity of good news and replaces it with good advice or good encouragement. We don’t need forgiveness; we just need fortitude. We don’t need a godly repentance; we just need a good response. Machen articulated the gospel of the modern liberal preacher in this way: “You people are very good; you respond to every appeal that looks toward the welfare of the community. Now we have in the Bible—especially in the life of Jesus—something so good that we believe it is good enough even for you good people.” In Machen’s day, a do-goodism of the self had usurped the good news of a Savior.

Machen’s astute and perceptive critique of modern liberalism still holds true in our day. And the church’s response ought to be the same as in Machen’s day: an unembarrassed, unashamed reaffirmation of the distinction between God and man. The church must understand God and man on His terms, not our terms. In this respect, the Scriptures provide two key aspects of the gulf that exists between God and man.

First, there is the Creator-creature distinction. Genesis begins with an affirmation of God’s transcendence: “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth” (1:1). By good and necessary consequence, several truths about God may be deduced from this opening sentence of Scripture: God is one, not many; He is simple, not composite; He is eternal, not temporary; He is spirit, not matter; He is infinite, not finite; He is unchangeable, not changeable; He is self-existent, not dependent; He has life in Himself, not from another self; He is immortal, not mortal. In short, God is the transcendent Creator, set apart. And since man is created, not Creator, he is called to glorify God the Creator and enjoy Him forever. It is what the angelic creatures in heaven have been doing since the beginning of creation: “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of hosts; the whole earth is full of his glory!” (Isa. 6:3).

Second, there is the holy-sinful distinction between God and man, which came about because of the fall. Before the fall, man was distinct from God in the creature-Creator relation, but he possessed an original righteousness that enabled him to enjoy fellowship with God. It was righteousness under probation, however, and so the fellowship could be lost. When man fell into the state of sin through Adam’s transgression, the fellowship was broken and a gulf was fixed between God and man that was as infinitely great as the Creator-creature divide, only now infinitely more serious. In his temple vision, the prophet Isaiah vividly captures the significance of this holy-sinful divide. His “wow” response at seeing and hearing God’s thrice-holy nature is soon followed by his “woe” response at understanding his own sinful nature in the exposing light of God’s holiness (Isa. 6:1–5).

If the Creator-creature distinction between God and man reflects the original created reality, the holy-sinful distinction reflects the present existential reality. As such, it reveals the great predicament for mankind: How can fellowship between a holy Creator and a sinful creature be restored? The message of Christianity is that God has provided such a solution in His Son, Jesus Christ—the holy God-man. Jesus was all that God was and at the same time all that we are, and thus through His redeeming work, He is able to reconcile God and man. This is the simple yet profound good news of Christianity: God and man may be reconciled through the God-man, Jesus Christ. This is orthodox Christianity, the Christianity that Machen worked so fearlessly to defend and that modern liberalism still works so fiercely to oppose.