Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

Given the intensity of the unfolding ethical crisis in the Western world today, the church must redouble its efforts to learn doctrine. We, of course, must continue to encourage Christians to live out the Christian life and to speak out in favor of God’s gift of marriage and God’s creation of men and women in His image. We must thoughtfully address the sad fact that public knowledge of the chief end of man is systematically suppressed in a world where people are assaulted, aborted, and consumed with fine food, junk food, more sex, better screens, free drugs, and worldly dreams. But we especially need doctrine.

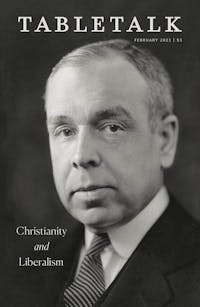

J. Gresham Machen wrote his classic book a century ago when the church was facing, among other things, enormous ethical challenges, some of them greater than he himself could conceive. In his day, ministers posing as prophets insisted that the real task of the church was to address the urgent need for improved democracy, civility, and moral reform. He himself insisted that a faithful church, especially a church in crisis, must believe and teach doctrine.

But why doctrine? Before and since Machen’s day, the church, especially in the face of social turmoil and ethical ambiguity, has often been tempted with tastier-looking options than Christian doctrine. Some teachers insist that the church has no creed but the Bible. People in the pew have no need for doctrinal excess and the subtlety of seventeenth-century confessions or catechisms. This has a certain plausibility. And as Machen says, speaking of the common man in the pew, “Since it has never occurred to him to attend to the subtleties of the theologians, he has that comfortable feeling which always comes to the churchgoer when someone else’s sins are being attacked.” But as Machen explains, after one hears about the dead orthodoxy of the creeds or the Puritans, and then turns to read the Westminster Confession of Faith or John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, “one has turned from shallow modern phrases to a ‘dead orthodoxy’ that is pulsating with life in every word.” What is more, Machen points out, under the guise of critiquing crusty old confessions, those opposed to doctrine are often opposing the Bible and its most basic teachings. And, we might add, those teachers most opposed to doctrine often set themselves up as the standard to follow.

Machen was principally dealing with people who had devious motives for opposing doctrine. They claimed to oppose doctrine in general because it was easier to sell than the honest admission that they had problems with some doctrines in particular: the virgin birth of Christ, His bodily resurrection, and more. But others have opposed doctrine because they are trying to follow Jesus, and Jesus Himself “just told stories.” Some scholars have added that this is the main approach of the whole Bible: it presents narrative and poetry, not systematic theology. Certainly narrative—or better, history—is important for Christians. We have a historical religion: Jesus taught this in the way that He spoke about the Old Testament; early Christians valued this, as we can see in Luke’s explanation of his own research; and the Apostle Paul announced this when he reminded the Corinthians of the historicity of Christ’s life, death, and resurrection (1 Cor. 15:1–8).

Nonetheless, as Machen notes, the Bible is not content to simply offer us narrative, for added to the historical narrative is an explanation of that narrative—an explanation that adds its meaning, that turns facts into doctrines. “Christ died,” Machen would say—“that is history.” But “ ‘Christ died for our sins’—that is doctrine” (see 1 Cor. 15:3). This commitment to doctrine is seen in the writings of Paul, in the values of the first Christians, and in the teachings of Jesus.

There are those, many of them theological liberals, who believe that the Bible is merely a narrative. There are also those who think that Christianity is merely a life; it is about doing, not about believing. Here again Machen is helpful. He reminds us that statements beginning with the words “Christianity is” are statements that can be verified. We need only to look at the teaching of the Bible, early Christians, or even the longer history of Christianity to see if this is the case. There might even be some truth in saying that Christianity ought to be a life, not just a doctrine. But “the assertion that Christianity is a life is subject to historical investigation exactly as is the assertion that the Roman Empire under Nero was a free democracy.” And when we investigate this claim, we find, as stated above, that doctrine is an essential part of the Christian faith from the beginning.

Machen makes a strong case in his book that Christianity is at its heart a doctrinal faith. But why do we need doctrine, especially when confronted with the urgent problem of the Western world’s ethical collapse? At the dawn of this collapse, Machen offered a key insight that is still relevant today: Liberalism is in the imperative mood, telling us what we must do, “while Christianity begins with a triumphant indicative,” telling us who God is and what He has done. In our historical moment, we are finding both “Christian” liberalism and aggressive secularism heavily prescriptive and preachy. There are now endless rules for public engagement, and even for ordinary conversation, stating what one must do, say, or not say. Liberal social and political life is now more than ever in the imperative.

Of course, we must challenge worldly imperatives with godly imperatives. But even more importantly, we must ground our imperatives in the Christian faith’s “triumphant indicatives.” In a recent conversation with a dear friend who surprised them with a “coming out” announcement, a Christian family was asked what they believe about human sexuality, and in time they shared some Christian imperatives: If we believe that God has made and now rules this world, we don’t get to make things up as we go along. There are ways to live life that honor God, and they are invariably designed for our good. They spoke about God’s gift of marriage and explained that God created us male and female, and in His image.

This was important to do. But arguably the most powerful moment in the evening came when a seventeen-year-old believer began to cry, explaining to her non-Christian friend that the Christian faith is beautiful, and she was weeping because her dear friend could not see this. This friend had reduced the Christian faith to a collection of imperatives—abhorrent imperatives in that friend’s mind. This young woman, on the other hand, knew the Christian faith to be a life that flowed from a doctrine, doctrine that offers life, peace, hope, and glory. And so she shared with her friend some doctrine, in the form of triumphant indicatives.

We must train Christians and even ourselves to know—and to defend—the law of God in all its fullness. But we must also understand how the indicatives of God’s Word ground and inform those imperatives, lest the message that we bring to a dying world not be as compelling or beautiful as it ought to be.