Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

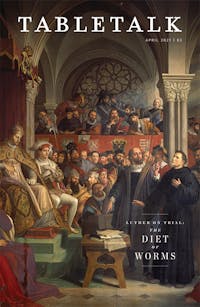

In the spring of 1521, Martin Luther and a few colleagues and a few students boarded a wagon and set out for Worms, a three-hundred-plus-mile journey from Wittenberg. Along the way, they stopped at Erfurt. As Luther’s carriage approached, a greeting party of forty horsemen trotted out to give the Reformer a hero’s welcome. City residents lined the streets, straddled walls, and perched on window ledges to catch a glimpse of Martin Luther. On April 7, 1521, he ascended the pulpit to preach to an overflow crowd that had spilled out onto the streets.

John 20:19–20 served as the text:

On the evening of that day, the first day of the week, the doors being locked where the disciples were for fear of the Jews, Jesus came and stood among them and said to them, “Peace be with you.” When he had said this, he showed them his hands and his side. Then the disciples were glad when they saw the Lord.

This text prompted Luther to ask perhaps the most significant question one could ask: How do we have peace with God? Luther personally felt the gravity of this question. Throughout his life, he felt no such peace with God. Instead, he felt terror, sheer fear. Oh, how this question troubled Luther. Peace with God means forgiveness. It means salvation. It means eternal life. Luther longed to hear these words from God directly to him: “Peace be with you.”

For the first thirty-five years of his life, Luther heard no such words from God. He heard only silence. He felt only judgment. He knew only darkness.

This gave Luther a deep sympathy for people and a righteous indignation for the medieval Roman Catholic Church. He looked to the church for salvation, for the way that would lead to peace with God. Instead, he found darkness obscuring darkness. Luther drew attention to this in the sermon preached that April Sunday in Erfurt. Luther observed that philosophers and great writers have explored this ultimate question of having peace with God and attaining salvation, but he focused on how the church—the church he was ordained in and excommunicated from—explored and answered this question. He reached a simple conclusion. The church taught that our works lead to salvation. This basic view undergirds all the faulty teaching that evolved over the centuries of the development of Roman Catholic teaching and practice. The idea that our works lead to salvation is a serious flaw, a seismic crack in the foundation. Luther was not the first to recognize this crack.

Forerunners of Reform

One of the earlier attempts at reform came in the fourteenth century in the Netherlands. Gerard Groote (1340–84) founded the Brethren of the Common Life, a monastic-style order that would be devoted to the ideals of early monasticism. Groote and his followers emphasized the renunciation of worldly goods and wealth, and they devoted themselves to prayer and the pursuit of piety free from worldly distractions. They lived communally. They established scribal centers and spent long hours laboriously, but artfully, copying pages of holy writ, especially the four Gospels.

The most well-known member of the Brethren of the Common Life was Thomas à Kempis (1380–1471). It is believed that he hand-copied the entire Bible at least seven times and copied many other books. He wrote books of his own, including biographies of Groote and of key members of the Brethren of the Common Life. He also wrote the classic text The Imitation of Christ.

À Kempis represents the attempts at reform that focused on piety. Many of the monasteries and medieval churches had lost their bearings. Rather than forsaking worldly things, they pursued them full throttle. Rather than devoting themselves to prayer, they neglected the spiritual disciplines and the practice of piety. But what Thomas à Kempis and his fellow brothers failed to see was that deep crack that ran all the way through the foundation. They failed to see that the church needed reformation at its very foundation. The church needed theological reformation, not just a reform of practice.

John Wycliffe (1330–84) was an early reformer who did see the crack in the foundation. An Oxford scholar who began his career in philosophy, he soon devoted his energies to biblical studies and theology. Wycliffe rejected transubstantiation and the papacy’s claim to be the head of the church. He also detested the church’s canon law that forbade the translation of the Bible into vernacular languages. He and his fellow Oxford scholars set about translating the Latin Bible, the Vulgate, into English. For all this, the pope condemned Wycliffe.

Wycliffe did enjoy some political protection. The mother of England’s monarch, King Richard II, favored Wycliffe, as did others highly placed in the king’s court and in Parliament. The pressure exerted by the church, however, prevailed. Wycliffe lost his post at Oxford and retired to a village where he served out his final days in a parish pulpit.

Wycliffe’s followers carried on the work after his death. They made hundreds of copies of the Wycliffe Bible—all by hand—and went from village to village armed with copies of God’s Word. Wycliffe’s books would also have an influence. They clearly influenced Luther’s early criticism of the church, and they influenced yet another forerunner of the Reformation, Jan Hus. All these reforming efforts have led us to call John Wycliffe the Morningstar of the Reformation. The dawn was approaching.

Jan Hus (1372–1415) studied in Prague, was ordained, and began teaching at St. Charles University and preaching from Bethlehem Chapel. Hus also took aim at the false teaching of the church. He advocated the singing of hymns in the Czech language, as opposed to the Latin antiphonals and liturgy. He advocated preaching in the Czech language. He also attacked a papal indulgence sale and regularly spoke out against the papacy. He translated and promoted Wycliffe’s books, which were on the banned book list. And he preached the true gospel of faith over and against the false gospel of works. He was summoned to the Council of Constance, arriving there on November 3, 1414. He was hoping for a debate; instead, the list of accusations was read out against him and he was commanded to recant. After a few weeks of refusing to recant, he was imprisoned on November 28.

Many long months of suffering followed, all as an attempt to induce Hus to recant. Church authorities gave up and on July 6, 1415, led him out of his prison cell through the city gate and about a kilometer or so to a prepared pyre. There Hus was martyred. He died with an unwavering faith in the gospel of Jesus Christ.

At one point, Hus had said that you can kill the goose, but a hundred years from now will come the swan, and you will not be able to kill the swan. Hus’ name means “goose” in the Czech language. He was saying that while the forces of darkness had the upper hand in 1415, these forces of reform in places such as England and Bohemia would continue to grow and, eventually, the gospel in all its splendor, beauty, and truth would prevail. The swan was coming.

Pre Lux Tenebras

What these pre-Reformation attempts at reform show us is the true state of the church and of life in the time leading up to October 31, 1517. We sometimes speak of the Reformation’s slogan at Calvin’s Geneva, Post Tenebras Lux: “After Darkness, Light.” The reverse is also true: “Before the Light, Darkness.” The darkness was felt theologically, religiously, and spiritually. There was also a darkness that was palpable socially, economically, politically, and educationally. Here’s one example. The first time that a law made wife-beating a crime in Geneva was not until the time of Calvin in that city—and that law was due to his influence. Here’s another example. John Knox used all the great wealth that had been accumulated by the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland to bring about educational reform in the entire nation. Through his efforts, Scotland achieved nearly universal literacy, a truly phenomenal feat in the sixteenth century.

But all this reform of society and politics and education came as a result of the Reformation’s reform not just of the church’s practice and liturgy but of the church’s theology. The true darkness that dominated the time leading up to the Reformation was the darkness of the obscuring and eclipsing of the gospel. The church taught that peace with God could be obtained through man’s works. That is the ultimate darkness. Eternal darkness.

The Reformers saw the seismic crack in the foundation. They boldly proclaimed the uncompromised gospel, and without flinching they called out medieval Roman Catholicism for preaching a false gospel, which is no gospel at all. When we see how the church and the popes responded to men such as Wycliffe and Hus, we see the grip of darkness. We see how darkness is threatened by the light. We see the lengths the darkness will go to to keep out the light. This sparked the righteous indignation Luther had for the church to which he belonged. This also explains the great sympathy Luther had for the German peasants covered in a blanket of darkness. Luther was one of the peasants himself.

A Law Degree, a Thunderstorm, and a Bible

The first son born to Hans and Margarethe Luther was baptized on November 11, 1483, one day after his birth. It was the Feast Day of St. Martin of Tours, and so he was named Martin. Luther’s parents had high hopes for their son and, when Luther showed academic promise early as a student, they made all the sacrifices they could for him. Luther’s early schooling took him to Magdeburg and then to Eisenach, and then he was ready for Erfurt, a town full of churches, monasteries, industry, and a university of increasing reputation. Luther earned his bachelor’s and master’s and set to earning his law degree. In the summer of 1505, Luther traveled home for an extended visit and some rest. On his way back to Erfurt, he found himself caught in a violent thunderstorm. Luther felt as if God had opened the torrents of heaven to take his very life. In fear, he clutched a rock and cried out, “Help me, St. Anne, and I will become a monk.” St. Anne, according to legend the mother of Mary, was the patron saint of miners, the guild of Luther’s father. His family would have had a small shrine to her in the home. Luther would have likely said prayers to her as he left. She was the only mediator he knew. When he felt what he thought to be God’s hand of judgment upon him, he turned to her for rescue.

As Roland Bainton says partly tongue in cheek, St. Anne kept her promise and Luther kept his. He turned his back on his law career and entered the monastery, joining the Augustinian order and beginning yet another trek through academic degrees in Bible and theology. It was here at Erfurt, as a student of theology, that Martin Luther would hold a complete Bible in his hands for the first time. Books were expensive, and a Bible was very expensive. But that’s not the only reason Luther never held a Bible. The church at the time was not interested in putting Bibles in the hands of people. For one reason, most were illiterate. But for another reason, the church did not want people reading the Bible for themselves. A family shrine, yes. A Bible in the home, no.

From 1510 through 1517, three significant things happened to Luther. First, he was sent on a pilgrimage to Rome. It was hoped that a visit to the Holy City would once and for all quell the demons that plagued Luther and the terror that gnawed at his soul. But when Luther found the Holy City to be nothing more than a den of debauchery and a sham, he felt utterly disillusioned by his church. The second significant thing was that Luther read Augustine. Through Augustine, he learned that no righteousness or merit he could ever earn would get him peace with God because Luther learned that he was unrighteous to his very core. Third, he read Paul, and for the first time in his life he learned that the righteousness God requires of us is not from or by us. It is an alien righteousness. It is God’s righteousness. Luther believed that salvation is by works. Of course, he vehemently denied that salvation is by our works. Instead, he gladly declared that salvation is by God’s work and that we are justified not by any merit or by any doing of our own but by grace alone through faith alone.

he has arrived at last

This was the uncompromised gospel that Luther preached from the lectern at the University of Wittenberg and from the pulpit of Wittenberg’s Saint-Marienkirche. This led Luther to pick up his mallet and nail the Ninety-Five Theses to the Castle Church door. This led Luther to the Heidelberg Disputation in 1518, where he thundered, “The cross alone is our theology.” It led him to Leipzig in 1519, where he debated Rome’s leading theologian, Johann Eck, and where Luther declared sola Scriptura—that Scripture alone is the infallible authority for the church. It was Luther’s preaching of the gospel that led Pope Leo X to issue the papal bull in the fall months of 1520, declaring Luther a wild boar in the vineyard and trampling underfoot the gospel. It was Luther’s preaching of the gospel that led him to be summoned to Worms in April 1521. If it was his preaching that caused him to be sent there, then he would preach along the way.

In that sermon in Erfurt, the city where he had held a Bible for the first time, on April 7, 1521, Luther said the church has given us all kinds of works to do. Pilgrimages, fasts, indulgences. It is all fable and fiction, darkness and lies. Luther counters, “Therefore, I say again, Alien works!” Christ is our justification, our redemption. If we believe in Him and His work of redemption in our behalf, we will have peace with God.

Martin Luther and his small band left Erfurt on April 14, 1521. They traveled to Eisenach and, in the shadow of the Wartburg towering over the city, Luther spent the night. They traveled all the next day. On the morning of April 16, they arrived on the bank of the Rhine River. A ferry carried them across, and around mid-morning Luther entered Worms to cheering crowds of thousands. It is recorded that a herald and a court jester greeted Luther. As Luther passed through the gate, the jester chimed, “The one we sought so long has arrived at last; we expected you even when days were at their darkest.”