Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

In 1978, Michael H. Hart published a book titled The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History. Any book like this will cause enormous debate by its very nature, and I myself strongly disagree with some of the author’s conclusions. For example, he places Jesus in third place—after Muhammad and Isaac Newton—and I cannot help but wonder if the author has ever considered why the publication date of his book is 1978 and not 1408 or 335. Our dates themselves are oriented by the years of Christ’s life. Muhammad and Newton were influential figures in history; Jesus is the Lord of history. But I digress.

The author ranks Martin Luther at number twenty-five on his list. I’m not going to quibble with the specific ranking because, aside from the ranking of Jesus on this list, I’m not sure it is possible to quantify influence with anything close to precision. I mention this book, however, because it does include Luther among the twenty-five most influential persons in all of history, and to be included in the top twenty-five out of several billion is quite an accomplishment. It means that Luther’s influence in history is obvious to all observers. Luther’s life and work significantly affected European history, the German language, the church, and theology, among other things. This article will look specifically at Luther’s theological legacy with a focus on the doctrines of justification sola fide and sola Scriptura.

To understand Luther’s theological legacy, we have to understand something of his theological heritage. There is a common popular-level misconception that in the Middle Ages, the Roman Catholic Church taught a simplistic doctrine of justification by works apart from grace and faith and that Martin Luther started the Reformation in 1517 by rejecting this doctrine and teaching justification by faith alone. The story is actually a bit more complicated.

It is important to understand, first, that at the time Luther was born in 1483, the church had yet to dogmatically define its doctrine of salvation as it had done with the doctrine of the Trinity and the person of Christ. Certain soteriological teachings, such as Pelagianism, had of course been declared heresy, but there was nothing comparable to the Nicene Creed or the Definition of Chalcedon on the doctrine of salvation. Second, what we find in the early and medieval church are a number of conceptual strands of thought regarding salvation. The strands of thought that were emphasized by a particular theologian depended to a large degree on other elements of his theology.

A theologian’s particular understanding of salvation will, for example, be dramatically affected by his doctrine of man, sin, and the fall. A theologian who believes Adam’s sin affected only Adam and a theologian who believes Adam’s sin affected all humanity will have different doctrines of salvation. A theologian who believes Adam’s posterity are born damaged by sin and a theologian who believes Adam’s posterity are born dead in sin will also have different doctrines of salvation. Similarly, a theologian who believes God has unconditionally elected a people for Himself and a theologian who believes God has elected those whom He foresaw would do their best will have radically different doctrines of salvation.

By the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the various conceptual strands of thought had produced more than one competing doctrine of salvation. There were those who adhered to a more or less Augustinian view. They tended to emphasize predestination, original sin, and God’s grace in salvation. They argued that because of the fall, man cannot come to God unless God gives the grace to do so. There were others, however, who taught that God gives grace to those who “do what is in them” (facere quod in se est). Their view of the effects of the fall tended to be very different from that of Augustine. In their view, man has the ability to turn to God.

It is also important to note that by the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the doctrine of salvation had become completely integrated with a complicated doctrine of the church and its sacraments, especially baptism and penance. Baptism was understood to be the instrumental cause of justification. Through baptism, one was brought into the state of grace where one remained until and unless one committed a mortal sin. Those who committed a mortal sin had to make use of the sacrament of penance to return to the state of grace. Compounding problems in Luther’s day was the widespread sale of indulgences, which were in effect an alternative to penitential works of satisfaction for those who could afford them.

In spite of the diversity of views, all medieval theologians emphasized salvation as a process of sanctification. The primary differences among them concerned the ability of man at the beginning of the process and during the process. The focus on salvation as a process was complicated by the fact that justification was not clearly distinguished from sanctification. In part, this is due to the fact that the Latin Vulgate, the Bible in use in the West during the Middle Ages, had translated the Greek word for “justification” with a Latin word that meant “to make righteous.” Augustine understood the word in this way, and theologians following him assumed that definition as well. This means that although early theologians could conceive of the difference between a forensic declaration of righteousness and an ontological making righteous, they couldn’t use the terms justification and sanctification to make this distinction. As the Middle Ages progressed, it became increasingly difficult to even state a conceptual difference between the two.

Martin Luther was educated by those late-medieval theologians who taught that God would not refuse to give grace to those who “did what was in them.” Luther taught this view in his earliest lectures. Gradually, however, he began to understand how seriously flawed that view was and began to reject the Pelagian tendencies in his thinking and move toward a more Augustinian view. Sometime between 1517 and 1520, Luther moved even further when he finally came to understand the distinction between justification and sanctification. He was helped along in this by Philip Melanchthon, whose expertise in the Greek language helped Luther come to a more biblically faithful definition not only of justification but of grace and faith as well.

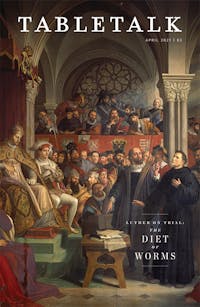

In these years between 1517 and 1520, as Luther began to raise objections to the practices of the church, his Roman Catholic opponents focused first and foremost on the question of authority. Luther was forced to dig deeper on this subject, and as he realized that various popes had contradicted themselves many times, he began to emphasize the idea that Scripture alone is our one infallible and divinely authoritative source for doctrine. Rome pushed back. Ultimately, Luther’s views led to his excommunication by the church and the call for him to appear before the emperor at the Diet of Worms.

Luther’s doctrine of Scripture and his doctrine of justification are arguably his two most important theological legacies. In both cases, he stepped into long-standing theological disputes and took a stand. In both cases, his stand forced Rome to respond, and in both cases, Rome chose views that had the least support in both Scripture and the historical church.

Luther’s legacy as regards his doctrine of justification finds its initial ecclesiastical expression in the Augsburg Confession of 1530 and the documents that resulted from it. The Augsburg Confession was written by Philip Melanchthon, but Luther heartily approved of it. The article on justification reads:

Also they [the Lutherans] teach that men cannot be justified before God by their own strength, merits, or works, but are freely justified for Christ’s sake, through faith, when they believe that they are received into favor, and that their sins are forgiven for Christ’s sake, who, by His death, has made satisfaction for our sins. This faith God imputes for righteousness in His sight. Rom. 3 and 4.

Regarding sanctification, the confession reads:

Also they teach that this faith is bound to bring forth good fruits, and that it is necessary to do good works commanded by God, because of God’s will, but that we should not rely on those works to merit justification before God. For remission of sins and justification is apprehended by faith, as also the voice of Christ attests: When ye shall have done all these things, say: We are unprofitable servants. Luke 17:10. The same is also taught by the Fathers. For Ambrose says: It is ordained of God that he who believes in Christ is saved, freely receiving remission of sins, without works, by faith alone.

The Augsburg Confession eventually became one of the confessional standards of the Lutheran church when it was included in the Book of Concord in 1580.

Luther’s legacy as regards his doctrine of sola Scriptura also finds its expression in the Book of Concord, in the Solid Declaration, where we read “that the Word of God alone should remain the only standard and rule of doctrine, to which the writings of no man should be regarded as equal, but to which everything should be subjected.” This is a concise summary of what Luther expressed at the Diet of Worms and elsewhere. It is a confessional way of saying, “Here I stand!”

Luther’s theological legacy is also found in the Reformed churches, whose confessions also teach sola Scriptura and the doctrine of justification sola fide. The Westminster Confession of Faith, for example, teaches the following concerning Scripture:

The whole counsel of God concerning all things necessary for His own glory, man’s salvation, faith, and life, is either expressly set down in Scripture, or by good and necessary consequence may be deduced from Scripture: unto which nothing at any time is to be added, whether by new revelations of the Spirit, or traditions of men. (1.6)

The doctrine of sola Scriptura as taught by Luther, the Lutheran confessions, and the Reformed confessions has been seriously misunderstood for centuries. Throughout most of the church’s history, Scripture was understood to be the sole source of divine revelation. It was understood to be the very Word of God and thus uniquely authoritative. Beginning around the twelfth century, a two-source view began to arise. According to this view, Scripture and tradition are two separate sources of revelation. Luther attempted to push the Roman church toward the older one-source view. Rome responded by moving to the two-source view.

Some of the more radical Reformers rejected both views and adopted a position that rejected any secondary authorities. For them, Scripture was the sole authority altogether. Pastors, confessions, and creeds were rejected. This was not the view of Martin Luther, John Calvin, or any of the other magisterial Reformers. This distorted version of sola Scriptura, however, has become endemic in the post-Enlightenment West. It is grounded in a serious misunderstanding of what the Reformers taught regarding the authority of Scripture. It is also completely at odds with what the early Reformers actually did in practice by writing dozens of confessions of faith.

The confessional Lutheran and Reformed churches understood the difference between Scripture and creeds. Scripture is the Word of God. Creeds are the words of men. Scripture is God speaking: “Thus saith the Lord.” The creeds are the church responding: “We believe.” The authority of the church’s creedal and confessional response is derivative and dependent on the inherently authoritative divine Word that it echoes in a communal response of faith.

The Westminster Confession also carries on Luther’s doctrine of justification:

Those whom God effectually calleth, He also freely justifieth; not by infusing righteousness into them, but by pardoning their sins, and by accounting and accepting their persons as righteous, not for anything wrought in them, or done by them, but for Christ’s sake alone; nor by imputing faith itself, the act of believing, or any other evangelical obedience to them, as their righteousness, but by imputing the obedience and satisfaction of Christ unto them, they receiving and resting on Him and His righteousness by faith; which faith they have not of themselves, it is the gift of God. Faith, thus receiving and resting on Christ and His righteousness, is the alone instrument of justification; yet is it not alone in the person justified, but is ever accompanied with all other saving graces, and is no dead faith, but worketh by love. (11.1–2)

One of the most important elements of the biblical doctrine of justification, as expounded by Luther and taught here by the Westminster Confession, is the idea that the righteousness of Christ is imputed to believers—placed on our record before God—and that Christ’s righteousness is the sole ground of our justification. In other words, we are not declared righteous because we have first been made righteous. We are declared righteous because Christ’s righteousness has been imputed to us. This is part of the great exchange. Our sins are imputed to Christ. His obedience is imputed to us.

The Westminster Confession goes on to address one of the most common misunderstandings of the doctrine of justification by faith alone when it states that this faith, although it is the sole instrument of justification, “is not alone in the person justified.” In other words, although justification must be distinguished from sanctification, the two can never be and are never separated in a person who is justified. Salvation involves both. There is a forensic element (justification) and a transformative element (sanctification).

Martin Luther’s theological legacy is one that we let disappear at great peril. By the authority of Scripture alone we learn that we are justified by faith alone in Christ alone. This is not only the article by which the church stands or falls; it is the article by which we stand or fall. It was this article that so radically transformed Luther. As Roland Bainton explains in the concluding paragraph of his great biography, Luther discovered that the almighty and holy God was also merciful:

But how shall we know this? In Christ, only in Christ. In the Lord of life, born in the squalor of a cow stall and dying as a malefactor under the desertion and the derision of men, crying unto God and receiving for answer only the trembling of the earth and the blinding of the sun, even by God forsaken, and in that hour taking to himself and annihilating our iniquity, trampling down the hosts of hell and disclosing within the wrath of the All Terrible the love that will not let us go. No longer did Luther tremble at the rustling of a wind-blown leaf, and instead of calling upon St. Anne he declared himself able to laugh at thunder and jagged bolts from out of the storm. This was what enabled him to utter such words as these: “Here I stand. I cannot do otherwise. God help me. Amen.”