Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

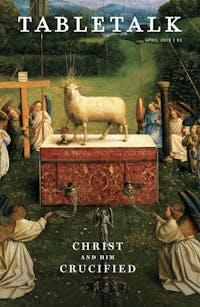

In the world of the first century, Roman crucifixion was not only a horrific form of torture, reserved for the lowest dregs of the criminal class, but it was also associated with severe shame. Not only were Roman citizens exempt from this humiliating death, but even the word crucifixion was avoided in social gatherings. In the Jewish mind-set, crucifixion was seen through the lens of Deuteronomy 21:23, which declares that anyone who hangs on a tree is cursed of God (see also Gal. 3:13). Given such a reality, how is it that the Apostle Paul, along with the rest of the New Testament authors, determined to know nothing but “Jesus Christ and him crucified” (1 Cor. 2:2), even to placard publicly Jesus as crucified in preaching (Gal. 3:1) and, indeed, to boast in nothing else except “the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ” (6:14)?

The answer lies, in part, in the sacrificial system of the old covenant temple. God, to the praise of His unsearchable wisdom, gave ancient Israel sacrifices to serve as theological tools, instructing His people about the remedy for sin and the need for reconciliation with God. After the resurrection of Jesus and the outpouring of His Holy Spirit, the Apostles were enabled to discern in the pages of the Old Testament Scriptures how the system of sacrificial worship had been divinely ordained for the sake of unfolding the wonders of Christ and His accomplished work on the cross (e.g., Rom. 3:21–26; Heb. 9:16–10:18). The categories of sacrifice enabled the paradigm shift to seeing the cross of Christ not as a source of deep embarrassment but rather—and wondrously—as God’s greatest gift to humanity and His highest demonstration of love for sinners (Rom. 5:8).

Two theological concepts of sacrifice are especially noteworthy for understanding the death of Jesus on the cross as the only sacrifice able to secure pardon from our sins and definitive reconciliation with God: expiation and propitiation. The first, expiation, means that Jesus’ sacrifice cleanses us from sin’s pollution and removes the guilt of sin from us. Propitiation refers to the assuaging of God’s wrath by Jesus’ sacrifice, which both satisfies the justice of God and results in His favorable disposition toward us. We turn now to consider these concepts more deeply by looking at their roots in the sacrifices of the Old Testament.

Expiation

Expiation refers to the cleansing of sin and removal of sin’s guilt. In the sacrificial system of Israel, blood was collected from an animal’s severed arteries and then manipulated in a variety of ways. Blood was smeared, sprinkled, tossed, and poured out. In Leviticus 17:11, the Lord declared that since “the life of the flesh is in the blood,” He gave Israel blood on the altar “to make atonement for your souls, for it is the blood that makes atonement by the life,” underlining the idea of substitution: the shed blood of a blameless substitute represented life for life, soul for soul. Blood’s importance was underscored most prominently by the sin offering. Through the shedding and manipulation of the sin offering’s blood, God taught Israel of their need for cleansing from sin and for the removal of sin’s defilement and guilt, making divine forgiveness possible (see Lev. 4:20, 26, 31, 35). On the one hand, the blood signified death: displaying the blood before God demonstrated that a life, albeit the life of an unblemished animal substitute, had endured death, the wages of sin. On the other hand, blood represented the life of flesh: by the principle that life conquers death, blood was used ritually to wipe away, as it were, the defilement of sin and death.

The Day of Atonement was essentially an elaborate sin offering (Lev. 16). On this autumn day, the high priest brought the blood of sacrifice into the Most Holy Place, sprinkling it before the atonement-lid of the ark, the earthly footstool of God. Blood was also sprinkled in the Holy Place and applied to the outer altar as well, cleansing both the Israelites and the house of God, the tabernacle, that He might continue to dwell among His people.

The one sin offering of the Day of Atonement involved two goats. After the first had been sacrificed for the sake of its blood, the other goat was symbolically loaded with the guilt of Israel’s sins as the high priest pressed both hands onto the head of the goat and confessed those sins over the animal. Weighed down with the judgment-worthy guilt of Israel on its head, the goat was then driven eastward, far from the face of God into the wilderness—a demonstration that “as far as the east is from the west, so far does he remove our transgressions from us” (Ps. 103:12). The sin offering, then, offered the Apostles a profound understanding of the death of Christ. While the blood of bulls and goats could never take away sins (Heb. 10:4), the blood of Jesus the God-man, shed on the cross and applied by the Spirit to those who trust in Him, cleanses sinners from their sins. The thorns pressed onto His brow, an image of humanity’s cursed estate (Gen. 3:18), were but a token of His bearing the weight of His people’s guilt on His head, further demonstrating that He endured our fiery judgment to provide us with true expiation.

Propitiation

Propitiation refers to the assuaging of God’s wrath and gaining of His favor. Turning to the doctrine of propitiation, we find a vivid portrayal of the assuaging of God’s wrath as we reflect now on the whole burnt offering. Israel’s worship was founded on the whole burnt offering, so much so that the altar, the central focus of worship, was even dubbed “the altar of burnt offering” (Ex. 30:28).

The first episode in Scripture where the whole burnt offering appears is in the story of the flood in Genesis 6–9. Early on, we are told that the Lord God, who is the main character in the narrative, was grieved “to his heart” over humanity’s corruption (6:6), and that He determined to punish the wicked while saving Noah and his household. The crisis of the story, then, is the aggrieved heart of God. Even after the waters of divine judgment had abated, however, the situation was not changed. God had not been appeased. His just wrath was not assuaged, until Noah, at the dawn of a new creation, built an altar and offered up whole burnt offerings. Using instructive language that attributes human traits to God, the narrative describes the Lord as smelling “the pleasing aroma” of the whole burnt offerings so that His heart was comforted (8:21). As a result of the pleasing aroma, God spoke to His own heart, vowing never to destroy all humanity in such a manner again, and He blessed Noah. Like fragrant incense, the smoke of the whole burnt offering ascended into heaven, the abode of God, and He, smelling its soothing aroma, was appeased. God’s heart was comforted—that is, His righteous wrath was satisfied. Later on through Moses, God ordained for the priesthood to offer up lambs daily as whole burnt offerings (Ex. 29:38–46). These morning and evening offerings served to open and close each day so that every other sacrifice—along with the daily life of Israel—was enclosed in the ascending smoke of their pleasing aroma.

The whole burnt offering’s divinely ordained impact on God leads one to wonder over its theological significance. The one feature that is unique to this offering is that the whole animal, apart from its skin, was offered up to God on the altar; nothing was held back. The whole burnt offering thus signified a life of utter consecration to God, which means a life of self-denying obedience to His law. In the words of Deuteronomy, this offering represented and solicited one’s loving the Lord God with all of one’s heart, soul, and might (6:5). Such a life—lived by Jesus alone—offered up to God ascends to heaven as a pleasing aroma and propitiates God.

Jesus fulfilled the Levitical system of sacrifice only because He offered Himself up to God on the cross as One who had fulfilled the law. In His tormented night of prayer in Gethsemane He had prayed, “My Father . . . not as I will, but as you will” (Matt. 26:39), and then He drank the cup of divine judgment as our blameless substitute. Jesus’ life of complete and loving devotion to God, offered up to the Father by the Spirit and through the cross—this is the assuaging of God’s wrath.

Because Jesus’ suffering was as a vicarious penal substitute, sinners can find rest for their souls. The impending thunderstorm of divine judgment that ever threatens us, overshadowing our vain attempts at happiness, cannot be dispelled by wishful thinking or misguided assertions. A Christian basks securely in the warm rays of the Father’s favor only because that storm of judgment has already broken in the full measure of its fury on the crucified Son of God. His shed blood cleanses us from our sins, removing our guilt from the sight of God. His wholehearted, law-keeping life offered up to God through the cross, even as He bore our penalty, rises to heaven as a pleasing aroma. Here, at last, the chief of sinners finds cause to boast in nothing at all except in the One who “loved us and gave himself up for us, a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God” (Eph. 5:2).