Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

When error comes into the church we face a set of obligations. First, we must confront the error. The world has embraced a live-and-let-live relativism that will accept any foolishness, but will not accept the wisdom of calling foolishness by its name. Too often the church follows suit. We want to get along, and so pet the wolves in our midst rather than drive them away. Our calling, as faithful soldiers of the kingdom, is to combat error in whatever form it takes. Second, we must not err when confronting the error. If we would have sound and accurate thinking in the church, we must be sound and accurate in what we denounce. We are not serving well the kingdom of God when we fight carnally, using gossip, innuendo, and aiming our fire at our allies. Consider the almost civil war during the time of Joshua. Those tribes on the eastern side of the Jordan, you’ll remember, built an altar. Their brothers prepared to make war against those who would establish false worship within the land. These brothers came to understand, thankfully, that the altar wasn’t built for false worship, but as a reminder of the covenantal union those on the east had with the rest of Israel. Far from an occasion for division, the altar was a monument to unity. Zeal without knowledge, in this instance, could have led to unnecessary division and senseless slaughter. (See Joshua 22 for the full story.)

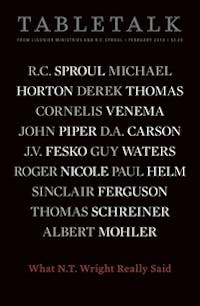

We are given these stories, told of these events that we might learn from them. Consider, in our own day, the battles in some of our institutions and on the internet over the doctrines taught by N.T. Wright, as well as those doctrines that collectively go by the moniker “Federal Vision.” It is certainly fair to say that the teaching of N.T. Wright has had an impact on what has come to be known as Federal Vision. Often those who celebrate the one celebrate the other, and those who condemn the one condemn the other. Such doesn’t mean, however, that the two should be conflated. We ought not, sloppily, accuse all who appreciate Wright of embracing Federal Vision, nor accuse all who appreciate Federal Vision of embracing Wright. Far less, however, should we be accusing those who embrace neither of embracing both, which has somehow happened to me. I have been charged in the past with Wright’s errors, and though I do not now, nor have I ever embraced Federal Vision theology, I have been charged with its errors too.

This difficult-to-define way of thinking hit most of our radars due to a conference held in 2002 at Auburn Avenue Presbyterian Church in Louisiana. The hosts there, noting the concern they had raised the year before, invited four critics to come speak to those concerns. As one of those four, I took the opportunity to argue that Federal Vision’s view of apostasy was, as far as I could tell, a denial, however unintentional, of the biblical doctrine of perseverance of the saints. That is a rather serious problem. One cannot deny perseverance, or affirm a system of thought that leaves little room for perseverance, and still claim to be Reformed or confessional. Neither can one claim to believe in perseverance if one affirms God predestined that some would come to saving faith and then lose that saving faith. The doctrine of perseverance has never merely affirmed that those whom God foreknew would persevere but rather affirmed that all those who trust in the finished work of Christ will persevere, will so trust until their death. In sundry venues, over the years, I have highlighted this same problem and in turn noted a long series of other problem areas within the movement. These include its sanguine approach toward Rome and Orthodoxy and the efficacy of their sacraments; Federal Vision’s often muddled language on the relationship between our works, perseverance, and future justification; and, of course, their often rancorous rhetoric. (To be fair, that particular charge is rightly leveled all around. This peculiar debate has not exactly been marked by gentlemanly behavior.)

Reformed orthodoxy affirms both that people do change, and that people do stay the same. That is, we become soldiers of the King only after God changes our hearts, blessing us with the gift of faith. Before we are drafted into the army of the Lord we are soldiers in the army of the serpent. We are by nature children of wrath. His Spirit changes us. This supernatural work of the Spirit is, of course, irresistible. Once we have been drafted into God’s army, once we have been given a heart of flesh, we can never go back. Our Captain, our King, our L ord, has promised that we shall never again serve the lord of darkness. Jesus has promised that nothing can take us from His hand. We are reminded that those who appear to leave us were ultimately never with us (1 John 2:19). One can no more defect from the L ord’s army than one can be disowned after being adopted into the family of God.

When Jesus commands that we seek first the kingdom of God and His righteousness, He leaves no room for not seeking the kingdom. Those who seek first the kingdom, by His grace and in His power, will seek always His kingdom. And praise God, He rewards all those who seek Him.