Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

There is no escaping that we serve a God of covenants. It is His habit to work through means. High on that list of means is faithful men with a vision that extends beyond their nose, men who purpose in terms of millennia, rather than forty days. Because we are in the throes of covenantal cursing, we do not know our fathers.

We are historical orphans. Somewhere along the line, someone forgot to explain the ebeneazors, and now we are adrift. We don’t know who we are, nor where we came from. Even our recovery is an anemic one, as we broadly study the broadest outlines of our history. The average layman knows nothing of church history. The studious layman knows of Luther, Calvin, and the glory days of the Puritans. Beyond that we are left to our own devices.

I believe we have this weakness, because I know I have this weakness. I know precious little but a few of my favorite stories, and a few of our precious creeds. When I first sought ordination in the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church, I was asked on the floor of presbytery what was meant by the name of the denomination. “Church,” “Presbyterian,” and “Reformed” were not a problem for me. But I had no idea what “Associate” meant. I was embarrassed, and rightly so.

There is a middle ground of church history that I have a passing knowledge of, something slightly less obscure than the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church, but slightly more obscure than Luther, Calvin, or Owen. I know that for several bright and shining, not moments but generations, God not only gave us teachers as He promised in 1 Corinthians 12:28, but He went so far as to give us teachers of titanic intellect and character all in one place. For the history of the Reformed faith in America, it seems that all roads lead to Princeton. You cannot know our story without knowing this story. The dean of Reformed theologians, Jonathan Edwards, served as the first president of what was then The College of New Jersey. His tenure wasn’t long, though the shadow he cast was.

A few generations later, God gifted the school, and the church, with a string of great men. Archibald Alexander served as professor of systematic theology. Charles Hodge, whose text is still widely used, served as professor of systematic theology. In honor of his greatest teacher, Charles Hodge named his son Archibald Alexander Hodge. A.A. Hodge honored his greatest teacher, his father Charles, by taking over as professor of systematic theology.

While God’s faithfulness is perfect, men are by nature adulterers. Even with these great gifts, Princeton eventually fell. Only a fool would go there looking to be taught the depths of the riches of God. And all he would get would be folly. On the watch when it happened was another titan, the last of the great Princeton men, J. Gresham Machen. When Princeton finally and fully embraced theological liberalism, Machen went elsewhere to champion something entirely different, Christianity. For him the choice was easy, and out of Princeton’s shame came Westminster Seminary.

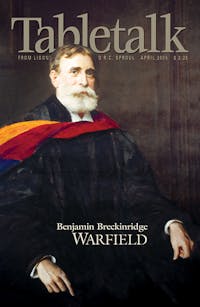

Between these two epochs, between the golden age and the great fall, however, there stood another great man, Benjamin Breckinridge Warfield. Machen had the honor of the split. He fulfilled the prophet’s role. He shook the dust off his feet and moved on. It was Warfield who fulfilled a different role. Machen dared to be a Daniel. Warfield wept like a Jeremiah. Machen, like Elijah, took the Joshua strategy, telling the watching world to choose ye this day, to choose between Christianity and liberalism. Warfield, before him, sought to stop the drift, defending the inspiration and authority of the Bible.

It is a judgment against our culture that we look for the flashy. Machen deserves our honor, for playing the role of the hero. Some times call for heroes. Like some postmodern loner, he stood his ground and was driven into the ground. Warfield’s place in our collective memory is less secure, because his faithfulness was less flashy. Heroes get carried away by flood tides. Ordinary boys try putting their fingers in dykes.

It is because we are worldly that we too want to be the lone hero. We are inspired by stories of rebels, no matter what their cause. We would rather die a dramatic death than to live in peace and quietness before all men. What drives all this is ego, and the hunger to live on forever. What kills this is Christ, and the hunger to live with Him. We must indeed fight the good fight in the culture wars. But we are losing, and not winning, if we seek to win for the sake of our fame. We are still feeding the same monster. More effective than spearheading a write-in campaign to save the one clean show on television is the more ordinary work of reading a story to your children. Better than having the liberals hate you, is having your children love you. Of course, no one comes and interviews on television when you do something like that. Which is a sign we’re on the right path. The path to winning the culture war, the war out there, is to win the sanctification war, the war in here. We will change the world only as we, by the power of His Spirit, change ourselves.

God once blessed Princeton. And He may yet do it again. But He will not do it because some theological cowboy came in with guns blazing. He will do it because some humble servant came to teach faithfully. He will do it by sending another prophet with the spirit of Warfield.