Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

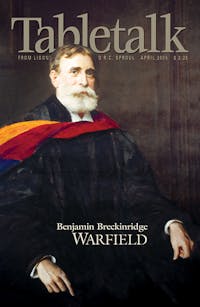

Truth is one of the most contested issues of our times. We now live in what Ralph Keyes has memorably named “the post-truth era.” Many intellectuals simply dismiss the idea of truth as a play on words and a claim to power. In the postmodern academy, truth is assumed to be unknowable or nonexistent — with nothing left but perspectives, prejudices, and opinions. For B.B. Warfield, truth was always the central issue. Even as the worlds of theology, biblical studies, and other academic disciplines were rejecting the very idea of revealed truth, Warfield represented a stalwart defense of truth as an absolute necessity for theology, worship, and the Christian life. Elected to the faculty of Princeton Theological Seminary in 1887, Warfield entered a world of theological engagement and for the entirety of his long and illustrious career, Warfield served as an apologist and a defender of the faith against challenges from without and within.

Warfield, along with his colleagues on the faculty of “old Princeton,” recognized the threat presented by modernism, theological liberalism, and the rationalism that would soon become dominant in American intellectual life.

Nevertheless, Warfield recognized that the most insidious threats faced by the church in his day came from within rather than from without the institution. Writing in 1894, Warfield would observe “that it is not a matter of small importance whether we preserve the purity of the gospel.” As he went on to explain, “The chief dangers to Christianity do not come from the anti-Christian systems. … It is corrupt forms of Christianity itself which menace from time to time the life of Christianity.”

Trained as a New Testament scholar, Professor Warfield would make his mark as a defender of the faith, a theologian, and a bold proponent of biblical inspiration. Even as the skeptics rejected the very idea of supernatural revelation, Warfield would defend the truth of God’s Word, arguing for the verbal inspiration of Scripture, the perfection of the Bible, and the eternal truthfulness of all that Scripture teaches.

Christianity, he argued, is established upon a foundation of truth, and that truth is found in a revealed book. Warfield would produce dozens of articles, book reviews, and essays — most addressed to issues of current concern and theological compromise.

Warfield’s concern for truth led him to argue that theology, as an explicitly Christian discipline, is impossible without confidence in the truth of the Bible. Without a firm grounding in biblical authority, theology becomes false prey to either pietism or rationalism. As Warfield would warn, “Pietists and rationalists have ever hunted in couples and dragged down their quarry together.”

Along with his Princeton colleagues, Warfield affirmed the necessity of true Christian piety. Though the Princetonians have been accused of reducing the Christian faith to “mere” assent to propositional truth, this charge is both inaccurate and misleading. As a seminary professor, Warfield was vitally concerned for the spiritual development and experience of his students — warning them that the study of theology is no substitute for true piety.

Nevertheless, Warfield keenly observed that, without confidence in biblical truth and a firm commitment to the authority of the Bible, the Christian experience is reduced to experience without substance or, in the case of rationalism, to an absolute rejection of supernaturally revealed truths.

In Warfield’s view, both of these roads lead to disaster. For this reason, Professor Warfield was a brave and consistent defender of confessionalism, creedal subscription, and the doctrinal standards of the church.

This did not always make Warfield popular. Even as the Northern Presbyterian Church was embroiled in controversy prompted by theological liberals such as Charles Augustus Briggs, Warfield entered the fray as apologist, defender of the faith, and contender for theological orthodoxy.

Even then, Warfield and his colleagues were charged with being narrow, small-minded, and defensive in light of the current intellectual climate. Warfield was undeterred, trusting that God would vindicate His truth and praying that God would preserve His church.

As Warfield observed, the church was endangered more by subversion from within than from outside attacks. He refused to allow theological liberals and revisionists to redefine Christianity itself.

With keenness of mind, boldness of spirit, clarity of thought, and an impassioned heart, Warfield took on many challenges. He never wrote a systematic theology, and his theological legacy is found in the hundreds of relatively short articles that speak with freshness and vitality even today.

B.B. Warfield should serve as an example for our day, reminding this generation that we too face challenges that are directed to the very heart of the faith. Like Warfield, we must be willing to name names, engage the world of scholarship, and defend the faith with vigor, honesty, and candor. Can we do less?