Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

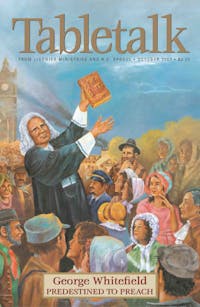

George Whitefield was so focused on preaching the Gospel in a dramatically new way that he did not directly address the immense social problems of the mid-eighteenth century: the slave trade, the massive abuse of alcoholic beverages, the crime, the dueling, the inhumane treatment of the mentally ill, the horrible prisons. Like Jesus, he saw the crowds who pressed in to hear his preaching, had compassion on them, and gave them the best gift, the Gospel of Christ.

His preaching was not at the expense of physical and social needs. He worked diligently to help one of those groups singled out in Scripture for compassion—orphans. He gave much time and effort to an orphanage project in Georgia, and he took personal care of orphans he met and guided them to orphanages. He also followed the Matthew 25 exhortation to visit those in prison. And he rebuked Southern slave owners for cruel mistreatment of slaves.

But he never called for the abolition of slavery, for a “war on poverty,” or for prison reform. John Wesley encouraged some of these initiatives in his later years, but Whitefield concentrated on the life-changing message of salvation in Christ for the next generation of men and women—and they, in turn, went on to apply the Scriptures to all areas of life.

William Wilberforce was one shining example of that next generation. At age 10, he went to live with his uncle and aunt, Robert and Hannah Wilberforce, because of his father’s death and mother’s sickness. His aunt and uncle were Whitefield supporters who would invite the evangelist to preach in their home. Wilberforce made some commitment to Christ in that home. He probably never heard Whitefield preach, because the evangelist was oft on his last trip to America, where he died in 1770. But his uncle and aunt also invited the ex-slave trader John Newton to their house to preach and would take William to hear him at church. Those childhood seeds of Gospel influence were not wasted. Wilberforce heard a defense of the Gospel in his early 20s, after his election to Parliament, and recommitted his life to Christ.

He soon wondered whether he should leave the political scene, with its gambling, drinking, and gluttonous habits, and find a more spiritual calling, such as the pastorate. For counsel, he called on Newton, who had become a pastor in London. Newton had benefited in his Christian growth from reading Whitefield’s sermons, later hearing him preach, and receiving his personal counsel and friendship. Newton’s counsel to Wilberforce about politics was a surprise. He told him to remain in the calling to which he seemed destined by natural skills and the circumstances of his birth. Wilberforce had been born to wealth, loved people, and had natural oratorical abilities that could be devoted to Christ’s kingdom. Newton knew that the slave trade could be halted only by someone like Wilberforce, well-connected socially and politically.

Thereafter, God put two objectives on Wilberforce’s heart—the abolition of slavery and the reformation of manners, or what we would call cultural reformation. Christ used Wilberforce to accomplish both objectives.

The social problems in the mid-1700s were far greater than anything known in the history of the United States. A. Skevington Wood, writing in The Inextinguishable Blaze, lists many problems, including widespread drunkenness and gambling, along with brutal entertainments such as cock-fighting and bull-baiting. Also, tenants were being thrown off common lands for farming, sparking a new problem of poverty in the cities and towns.

Whitefield’s evangelism laid the foundation for a major change for the better. Wilberforce and his friends, sometimes called the Clapham Sect because of where they lived in London, saw great progress in crime reduction; a sharp reduction in drunkenness; and the rise of the Sunday school movement, which laid the seeds for literacy and mass education of children in the next century.

Whitefield also influenced other key figures besides Wilberforce. For instance, in Gloucester, William King had come to salvation through Whitefield’s preaching and started visiting a prison to tell the inmates about Christ. King told his friend, Gloucester newspaper publisher Robert Raikes, about the need for sabbath schools to help the poor to learn to read the Bible. Raikes, a friend of Whitefield and John Wesley, caught that vision, started several sabbath schools, and then started writing about them in his newspaper. Reprinted in other publications, the stories fueled the growth of the Sunday school movement and evangelism among children.

J.R. Green, in his Short History of the English People, sums up the social impact of the Great Awakening, the great revival that was fueled by Whitefield’s preaching: “The revival changed in a few years the whole temper of English society. The church was restored to life and activity. Religion carried to the hearts of the people a fresh spirit of moral zeal, while it purified our literature and our manners. A new philanthropy reformed our prisons, infused clemency and wisdom into our penal laws, and abolished the slave trade.”

Whitefield, along with the Wesley brothers, also helped plant seeds of the world-missions movement of the late eighteenth century. He offered a boost to missions to the Indians in North America. And he indirectly contributed to American independence by preaching a Gospel of spiritual liberty, creating a foundation for the political liberty the Colonists sought in the next generation.

“His frequent traversing of the land from one end to another served notably toward creating a sense of unity between the previously disunited Colonies,” writes Arnold Dallimore, the great two-volume biographer of Whitefield. “When the Revolution was accomplished the principles of justice and equality written into the Constitution were principles that had been implanted in the public mind by the Awakening, more than by any other influence.”

In light of these great accomplishments, by such a great man of God, why couldn’t Whitefield see what Wilberforce and John Wesley saw so clearly—that slavery, as it was practiced in the British Empire, was a sin? John Wesley Bready, in his excellent book on the Great Awakening (England: Before and After Wesley) writes: “Whitefield, in brief, had held the popular delusion that the savage natives of Africa would profit finally by being brought within the influence of Christian lands, wherein ultimately they would purchase their freedom by special faithfulness. He did not reckon with the central fact of history, that slavery, by its very nature, tends spiritually to enslave the enslavers.”

But Whitefield actually saw more than we might realize. Few people of his day questioned the morality of chattel slavery. Unlike many, however, Whitefield believed the slaves were human beings in need of salvation, and preached to them and called for kind treatment of them.

An interesting question is whether Whitefield, who died at age 56 in 1770, might have changed his mind had he lived as long as Wesley. Certainly friends like Wesley would have tried to persuade the foremost evangelist to join them on this issue. What if he had changed his mind and joined Wesley in opposition?

Whitefield clearly never thought deeply about slavery. But his weakness illustrates the sovereignty of God and the way He takes our prayers and the Gospel message well beyond our limited vision. He certainly would shun any credit for the great advances that flowed from his preaching and would be surprised that believers hundreds of years later would be devoting an issue of a magazine to his life. He would just say, give God the glory and let the name of Whitefield die. “He who glories, let him glory in the Lord” (2 Cor. 10:17). From his life, we can learn once again to keep Jesus Christ at the center of all we do and to trust Him to use the Gospel to accomplish much more than we can ever imagine.