Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

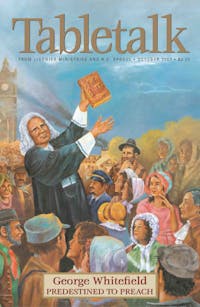

He was America’s first celebrity. Though just 25 years old when he began touring the sparsely settled Colonies in 1738, George Whitefield was an immediate sensation. And he remained so forthe rest of his life. Over the next 30 years, during some seven visits from his native England, he would leave his mark on the lives of virtually every English-speaking soul living on this side of the Atlantic.

“When he arrived in the Colonies,” says historian Mark Noll, “he was simply an event.” Wherever he went, vast crowds gathered to hear him. Commerce would cease. Shops would close. Farmers would leave their plows mid-furrow. And affairs of the greatest import would be postponed. One of his sermons in the Boston Common actually drew more listeners than the city’s entire population. Another in Philadelphia spilled overonto more than a dozen city blocks. Still another in Savannah drew the largest single crowd ever to gather anywhere in the Colonies, despite the sparse local population.

Some said he blazed across the public firmament like a “heavenly comet.” Some said he was a “magnificent fascination of the like heretofore unknown.” Others said he “startled the world awake like a bolt from the blue.” There can be little doubt that he lived up to his reputation as the “marvel of the age.” As historian Harry Stout has written, “He was a preacher capable of commanding mass audiences—and offerings—across two continents, without any institutional support, through the sheer power of his personality.”

By almost all accounts, he was the “father of modern evangelism.” He sparked a revival of portentous proportions—the Great Awakening. He helped to pioneer one of the most enduring church-reform movements—Methodism. And he laid the foundations for perhaps the greatest experiment in liberty the world has yet known—the American Republic.

All the greatest men of the day were in unabashed awe of his oratorical prowess. Shakespearean actor David Garrick said, “I would give a hundred guineas if I could say ‘Oh’ like Mr. Whitefield.” Benjamin Franklin once quipped, “He can bring men to tears merely by pronouncing the word Mesopotamia.” And Sarah Edwards—the astute and unaffected wife of the dean of American theologians, Jonathan Edwards—remarked, “He is a born orator.”

But he was equally beloved for his righteous character. George Washington said, “Upon his lips the Gospel appears even to the coarsest of men as sweet and as true as, in fact, it is.” Patrick Henry mused, “Would that every bearer of God’s glad tidings be as fit a vessel of grace as Mr. Whitefield.”

But not everyone welcomed his message. Whitefield emphasized that a comprehension of grace would naturally prompt whole-hearted righteousness—thus, there was actually no contradiction between the requisites of Christian holiness and the prerogatives of Christian liberty. This was equally an offense to the man who desired no accountability to a moral standard whatsoever and the man who desired to reduce the faith to a series of mere moral demands. To both the lawless and the legalist, Whitefield’s message of life in Christ was intolerable.

Thus, despite his wide acclaim and popularity, Whitefield was often ridiculed, scorned, and persecuted for his faith. Hecklers blew trumpets and shouted obscenities at him as he preached. Enraged mobs often attacked his meetings, robbing, beating, and humiliating his followers. Whitefield himself was subjected to unimaginable brutality—he was clubbed twice, stoned once, whipped at least a half-dozen times, and beaten a half-dozen more. And he lived constantly under the pall of death threats. Once, he recorded in his journal: “I was honored with having a few stones, dirt, rotten eggs, and pieces of dead cats thrown at me. Nevertheless, the Lord was gracious, and a great number were awakened unto life.”

Amazingly, it was not just the profane who condemned Whitefield’s work. He was also violently opposed by the religious establishment. Accused of being a “fanatic,” of being “intolerant,” and of “fanning the flames” of “vile bigotry,” he was often in “more danger of attack from the clergy than he was from the worldly.”

It took great tenacity and courage to sally forth as he did, when he did, and how he did. Whitefield biographer Arnold Dallimore says, “Whitefield’s entire evangelistic life was an evidence of his physical courage.” He fearlessly faced his opposition and continued his work. Though often stung by the vehemence of the opposition he faced, he refused to take it personally, attributing it rather to the “offense of the Gospel.” Instead, according to Dallimore, “He sallied forth with great determination and evident valor.”

May God be pleased to give us the courage of Whitefield as we sally forth into our own culture and our own day.