Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

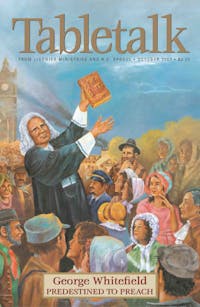

The figure of George Whitefield casts a large, rich shadow over the history of the church, and general history as well. It’s a shame that secularists have, to some degree, ignored this magnificent man, for he’s a major figure of the eighteenth century and important to understanding the time period. The profound influence of the work God did through him was great then, and remains great today. Perhaps his life has been largely ignored or distorted—a common response to major Christian figures—due to the fact that the intensity of such a godly life forces a response, either that of repentance before the God he serves, or a more fierce antagonism against that God.

Whitefield also has been, to some extent, forgotten by the Christian populace, possibly due to the destructive phenomenon of the contemporary church’s willful neglect of church history. This cavalier and, at times, even hostile posture has produced generally tragic results. Besides increasing our propensity to forget or distort doctrinal formulations of the past, and the particular reasons why they were set down (primarily in defense against the philosophies of enemies to the Christian faith), this attitude renders the writings and voices of many saints and martyrs mute. I would include Whitefield among these saints, for I have rarely, if ever, read of—apart from Biblical personages—a more superb example of a Christian working out his own salvation with fear and trembling.

As an antidote to this neglect of so great a man of God and of some of the lesser-known, yet important, figures surrounding him, such as John Cennick and Howell Harris, I would strongly encourage you to read George Whitefield: God’s Anointed Servant in the Great Revival of the Eighteenth Century. This work is a condensed version (219 pages) of Arnold A. Dallimore’s definitive, well-received two-volume set titled George Whitefield: The Life and Times of the Great Evangelist of the Eighteenth-Century Revival.

This very well-written, researched, and documented book traces Whitefield’s life, highlighting the most important and exciting events. Some of the main elements emphasized are the style and effects of his preaching, his doctrinal convictions, the course of his friendship with Charles and John Wesley, the phenomenon of the Great Awakening, the persecutions he suffered, his perseverance, his travels to different countries, and the progression of his ministry through its various stages.

One powerful aspect of this work is the emphasis Dallimore places on quoting from Whitefield’s journals and letters, and from those who heard him. These quotes appropriately serve as the primary source for Dallimore’s effort to faithfully convey the events in Whitefield’s life as they actually happened. Of course, many other supplementary sources are quoted to offer a fuller representation of Whitefield’s life and ministry. These quotes often come from the writings of those who knew him or were alive during the time period, such as the Wesley brothers, Benjamin Franklin, Jonathan Edwards, and the countess of Huntingdon. But the quotes attributed to the eloquent tongue and pen of Whitefield far exceed those of anyone else.

Whitefield’s words alone are a wealth of spiritual treasure. For example, Dallimore recounts how, on Sept. 29,1770—the day before his amazing life came to an end—the very ill Whitefield showed that his passion remained unabated. Before giving his final sermon, he was heard to say: “Lord Jesus, I am weary in Thy work, but not weary of it. If I have not yet finished my course, let me go and speak for Thee once more in the fields, seal Thy truth, and come home and die.”

Another unique facet of Dallimore’s work is his talent for attending to the necessary details in Whitefield’s life and in the lives of other figures surrounding him. This skill involves making careful choices concerning what details to include and what to winnow away. Dallimore’s ability is evident in his concern to correct abuses and distortions, which other writers have fostered due to bias or less-than-careful research. In keeping with the author’s integrity, not only does he deal with such disputed issues as Whitefield’s ability as an organizer and the question of who really founded Methodism, but he also reveals the one major blot on Whitefield’s career (you’ll have to read the book to find out what it is). In short, Dallimore is a master biographer (and a prolific one by the way, for he has written many books, including one about Charles Wesley and one on Charles Spurgeon).

Perhaps a quote from Dr. Cornelius Van Til’s introduction might serve best to encourage you to read this work. He states: “Read this book. You may forget to talk to your wife (or husband); you may forget to go to work; but it’s worth a few sacrifices.”

God’s Anointed Servant is published by Crossway Books.