Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

“From childhood you have known the Holy Scriptures, which are able to make you wise for salvation” (2 Tim. 3:15).

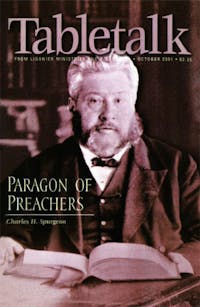

Charles H. Spurgeon is unique in the history of the church. He had no university or seminary degree. He was known for his preaching not his scholarship. And yet, he left a body of published work that represents the most prolific individual output of any well-known Christian in history.

A Precocious Child

Spurgeon was born in a little cottage in Kelvedon, Essex, on June 19, 1834. Both his father and grandfather were pastors. Eighteen months later, when his mother was about to deliver a second child, Charles was sent to visit his grandparents in nearby Stambourne. Apparently, mother or newborn suffered some long-term illness or complication, so the boy’s stay in his grandparents’ home was extended, then extended again. He did not return to live with his parents until he was 6.

The arrangement worked well for all. James Spurgeon loved having his eldest grandson by his side and often took the toddler with him on pastoral visits. In the providence of God, young Charles’ years of bonding with his grandfather set the course for his life.

Charles was a gifted child who began reading early. He loved his grandfather’s Puritan library. At first, it was the leather covers that interested him the most, but he soon found the books themselves to be a rich source of wisdom and interest. It was from his grandfather’s library that he obtained his first copy of Pilgrim’s Progress, and that book became his lifelong favorite. Before the age of 10, he was reading (and apparently comprehending) some of the richest theological works ever written.

Spurgeon was precocious in other ways, too. By the time he returned to his parents’ home, he already had three younger siblings, and the 6-year-old was deeply conscious of his responsibility to influence them for good. This maturity was surely the legacy of his grandfather’s example. Before he reached his teens, his hobbies were writing poetry and editing a magazine. He was honing the literary skills that would make him legendary. Shortly before his conversion at age 15, he wrote a 295-page book titled Antichrist and Her Brood, or Popery Unmasked.

Look at Spurgeon in any stage of his development and you will see someone wise beyond his years, with an exceptionally mature outlook on life.

A Burdened Sinner

Spurgeon is sometimes erroneously portrayed as a careless unbeliever who was suddenly, almost by accident, converted to Christ when he walked into a warm church on a cold night. Nothing could be further from the truth.

When Spurgeon was 10, he began to be deeply convicted by the realization that he had no saving knowledge of Christ. He set out on a quest for salvation that was to last five years. It was an agonizing time of life for him. The knowledge that he was not a true Christian was a heavy burden that was perpetually at the forefront of his consciousness. Here’s what Spurgeon wrote about those dark years of conviction:

When I was in the hand of the Holy Spirit, under conviction of sin, I had a clear and sharp sense of the justice of God. Sin, whatever it might be to other people, became to me an intolerable burden. It was not so much that I feared hell, as that I feared sin; and all the while, I had upon my mind a deep concern for the honour of God’s name, and the integrity of His moral government.

Conversion came through unlikely circumstances. One Sunday morning while Spurgeon was desperately seeking salvation, a terrible snowstorm virtually shut down the little town of Colchester. It was January 6, 1850, and the snowstorm grew worse just as Spurgeon began to make his way to church. He turned down a side street and ducked into a different church, a tiny Primitive Methodist chapel, where a service was just under way with no more than 15 people in attendance.

Apparently the regular pastor could not get through the blizzard that morning, so a reluctant and inarticulate layman finally got up to deliver the morning sermon. The man was obviously inexperienced and unprepared. He chose for his text Isaiah 45:22: “ ‘Look to Me, and be saved, all you ends of the earth! For I am God, and there is no other.’ ”

After reading the text, the man began his exposition: “Now lookin’ don’t take a deal of pains. It ain’t liftin’ your foot or your finger; it is just, ‘Look.’ Well, a man needn’t go to college to learn to look. You may be the biggest fool, and yet you can look.”

Spurgeon said the man couldn’t even pronounce some of his words correctly, and he ran out of material within a few minutes. But then, fixing his eyes on the one conspicuous visitor in the place, he said directly to Spurgeon, “Young man, you look very miserable.” Then he added at the top of his lungs: “Young man, look to Jesus Christ. Look! Look! Look! You have nothin’ to do but to look and live.”

Spurgeon said, “I saw at once the way of salvation.… I had been waiting to do fifty things, but when I heard that word, ‘Look!’ what a charming word it seemed to me!”

The burden was immediately lifted, and Spurgeon was filled with a joy he had never known. “I thought I could dance all the way home. I could understand what John Bunyan meant when he declared he wanted to tell the crows on the plowed land all about his conversion. He was too full to hold. He must tell somebody.”

The Prince Of Preachers

The following year, Spurgeon transferred to a school in Cambridge, joined a Baptist church there, and preached his first sermon in a house meeting. His preaching gift was immediately evident, and he soon was asked to fill the pulpit of a small church in Waterbeach, six miles from Cambridge. He promised to preach only a few Sundays, but he ended up remaining there for more than two years. Those circumstances made it impossible for him to pursue any more formal education.

But his fame as a preacher quickly grew, and in December 1853 he was asked to candidate at the New Park Street Baptist Church, the largest and best-known Baptist congregation in London. Its historic pulpit had been occupied in previous generations by John Gill, Benjamin Keach, and John Rippon—all Baptist legends. Although the country boy felt awkward in the large city, the congregation warmed quickly to his preaching and soon called him to be their pastor.

And so, exactly five years and one day after his conversion, Spurgeon preached his first sermon as pastor of the congregation he would shepherd for almost 40 years until the day he died. He was soon preaching weekly to crowds numbering ten thousand and more. (He once preached without amplification to a crowd of nearly twenty-four thousand.) Under his ministry, the New Park Street Church outgrew its facility and built Metropolitan Tabernacle in the heart of south London. Membership under Spurgeon’s leadership exploded from 232 to fifty-three hundred.

More than twenty-five thousand copies of Spurgeon’s printed sermons were sold weekly. The sermons were compiled in 63 thick volumes that are still being published today. They comprise some 25 million words.

Spurgeon never attended an hour of seminary; he seems to have sprung full-grown into maturity as a preacher and theologian. But the truth is that there were many circumstances arranged by Providence that made Spurgeon what he was.

There was his father’s and grandfather’s influence, of course. And there were all those Puritan works he began reading as a child. Spurgeon had an incredible, near photographic memory, and he could read a book once and remember years later exactly where to find a section he wanted to quote. Into his life as a Christian he drew with him an encyclopedic knowledge gleaned from a childhood of intense interest in spiritual things.

One other profound influence on Spurgeon should be mentioned. In the autumn before his conversion, he attended a private school in Cambridgeshire. The cook and housekeeper there was a woman named Mary King. Spurgeon often said afterward that he was indebted to her for much of his theology. She enjoyed discussing theology, and in Spurgeon she found a kindred spirit. She was a strong Calvinist who loved the doctrines of grace. Spurgeon said he “learned more from her than … from any six doctors of divinity of the sort we have nowadays.”

Obviously a number of factors combined to make Spurgeon the great preacher we remember. But what stands out most remarkably is that the foundation of his ministry was established in his childhood years. He stated near the end of his life that, after 40 years of ministry, he hadn’t moved an inch from the convictions he held when he began his ministry. To a large degree that was because such a solid character and such strong convictions were shaped by so many wonderful childhood influences.