Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

We Calvinists have what the professionals call an “image problem.” Our ratings are dropping fast. Sure, Calvinists are known for being smart; no one doubts that. But these are not good days for being smart. What is wanted in our day is sensitivity, and Calvinists do not get high marks for that. We are known as the “frozen chosen.” We are said to have calculating minds and, worse, cold hearts. We are seen as being as miserly in our emotions as we are careful in formulating our theology. We are caricatured as unconcerned about those who are suffering (it is, after all, God’s will) and about the lost (God will save those He has elected, and it’s pointless to worry about the non-elect).

Our heroes are not much help either. Calvin, most people imagine, never smiled, except perhaps while Servetus was burning. Cotton Mather is remembered not for his celebration of the providence of God but for presiding over witch trials. Jonathan Edwards always looked like someone had spiked his lip balm with persimmon juice. This image is so much a part of the popular understanding of what it means to be a Calvinist that a person who heartily affirms the five points of Calvinism and yet has a warmth, compassion for the suffering and lost, and a sense of humor can slip under the radar screen and pass as something else entirely.

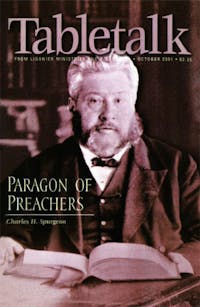

This explains why so many can maintain at the same time a deep distrust of Calvinists and a deep love for Charles Haddon Spurgeon. This explains why we test the credulity of some folks when we make the claim that Spurgeon was a Calvinist. But it’s not a difficult claim to defend. To prove the point, we do not need to find an obscure footnote in an obscure work in which Spurgeon says something like “Calvin wasn’t the Antichrist.” The great Baptist preacher himself said, “Calvinism is just a nickname for Biblical Christianity.” Spurgeon not only was not an Arminian, he was not the bane of too many Reformed pulpits, a whispering Calvinist. He was no more ashamed of his Calvinism than he was ashamed of the God who elected him to life. Spurgeon never whispered anything, including his commitment to the doctrines of grace.

Some would respond to the news of Spurgeon’s commitment to Calvinism with that gracious covering: “Many men are better than their theology.” They would affirm that there is a necessary connection between the coldness and the Calvinism, and that if Spurgeon had the one but not the other, well then, he couldn’t really have had the one. He may have said he was a Calvinist and thought he was a Calvinist, but he couldn’t have been one. I suggest not that he overcame his theology, but that he lived his theology like few men before or since.

Spurgeon’s concern and compassion for the lost, for instance, flowed out of, rather than against, his commitment to Calvinism. The Calvinist preaches to and prays for the lost, not because he has forgotten his Calvinism but because he has remembered it. We affirm that God is mighty to save. It is the other guys who worship a gentleman god who waits for an invitation. We worship the God who breaks down doors, not one who timidly knocks.

We worship, however, a God who saves by faith, not by election. And we know that the Scriptures tell us that faith comes by hearing. We do not not preach because we know that whatever God has ordained will come to pass, but we go out preaching the Gospel with confidence because we know that whatever God has ordained will come to pass.

Because Spurgeon was a Calvinist, he understood that the heart of the natural man is deceitful and wicked. He knew no man would come to Christ outside the sovereign intervention of the Holy Spirit. He knew also that we always seek out ways to take credit for the work of God in us, and so as he preached redemption, he preached redemption through the sovereign work of God. He did not pray like a Calvinist and preach like an Arminian. Neither did he pray like an Arminian and preach like a Calvinist. Rather, he prayed and preached as he was, as a Calvinist. Because he was a Calvinist, he understood that “he who wins souls is wise” (Prov. 11:30).

Spurgeon the Calvinist was not, however, exclusively concerned with the hereafter, the sweet by and by. His compassion led him to establish powerful mercy ministries in London and across Great Britain. This, too, was not in spite of his Calvinism, but because of it. Understanding the depravity of man, Spurgeon saw the need for these missions of mercy. He understood that God ordains not only ends but means, that orphanages and hospitals were not man’s attempt to undo the ravages of sin but God’s means of showering grace upon His world. And so, confident in God’s sovereign provision, he acted.

Spurgeon the Calvinist not only could weep for the lost and the broken, he could rejoice in the presence of God. He was not given to gnostic distaste for the physical realm, but rather had a taste for God’s good gifts. Indeed, Spurgeon rejoiced coram Deo, before the face of God. He knew it was the sovereign God who had put food on his table, and so he partook in joy. He knew it was the sovereign Christ who had turned water into wine, and so again he partook in joy. He knew it was the sovereign Spirit who had brooded over the unformed earth and birthed there all manner of gifts for men, and so in joy he took his cigars (in moderation—never more than one at a time). Spurgeon was a man who worked hard in building the kingdom of his Lord. And he was a man who played hard, understanding that he was at play in the fields of the Lord. He not only labored and rested coram Deo, he did so with great knowledge of that truth, and with great joy.

May we all learn to be true Calvinists, those whose hearts weep for the lost and hurting, and leap for the very glory of God that surrounds us. Let our image problem not be that we are too cold, but that we are too hot, not that we are too narrow, but that we are too expansive, as it was with Spurgeon, the prince of preachers and a hero of the faith.