Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

Augustine was born at the climax of the Christian era of the Roman Empire, lived during the decades of Rome’s decline, and died as the Vandals were at the gates of Hippo. He lived squarely in between two major ecumenical councils of the early church, Nicaea in 325 and Chalcedon in 451. He is arguably the most important figure, beyond Jesus and the disciples, in the first millennium of the church, and perhaps of all time. His shadow is cast over the development of every major doctrine, including the Trinity, the doctrines of grace, the doctrine of Scripture, and eschatology (the doctrine of last things). While he was not always right, at times his Platonism wielding undue influence, he is clearly a major constellation. It took many decades for Augustine to confess to God that “You use all, whether we know it or not, for a purpose which is known only to You.” In context, the “all” refers to every event of his life, every twist and turn, every one-step-forward and two-steps-back, every defeat, every victory, every disappointment, and every celebration.

wanderer

On November 13, 354, Augustine was born on the north coast of Africa in the town of Thagaste in the region of Numidia, part of the vast Roman Empire. Numidia is related to the word nomad, and the settlers of that region were Berber nomads brought into the fold of Rome during the Punic Wars of the 200s and 100s BC. Augustine’s father, Patricius, was a pagan and his mother, Monica, was a devout, and at times mystical, Christian. She would come to take her own place in church history as one of its most famous mothers. Augustine had at least one brother that we know little of, Navigius, and at least one sister, whose name we do not know.

Thagaste was situated on a fertile plain, one of the most fertile areas in all Africa. Lions and tigers roamed the surrounding mountains. The town was full of retired Roman soldiers. Farming and soldiering had no appeal to Augustine, however. His sights were on the academy. As a ten-year-old he was off to Madaura, a university town about fifteen miles away. Augustine went, saw, and conquered. He tells us that he studied “literature and the art of public speaking.”

Augustine returned to Thagaste in 370, and next followed the incident that occupies book 2 of The Confessions. That chapter x-rays sin and finds that sin is “chasing shadows.” The sins of the flesh and the body’s appetites “plunge us into a whirlpool of sin.” To make this tangible, Augustine confesses his great sin of taking some pears. He was with his friends, and they were wandering through a neighbor’s property and stole pears. Augustine confesses that he had no wish to enjoy what he stole but desired only to enjoy the theft itself. He sinned because he wanted to. But, he confesses, the sinful act left him empty and unhappy.

Having learned all he could at Madaura, Augustine went to Carthage, the second- largest city in the Roman Empire at that time. Again, Augustine excelled at learning. But all his success left hvim unsatiated. Carthage is cartago in Latin. The Latin word sartago means “frying pan.” And that is what Carthage was. With a massive port, lots of money circulating, and very powerful people coming and going, Carthage was a “frying pan” of sin. Augustine liked the wordplay Cartago-Sartago, “the city that is a cauldron of sin.” Augustine felt acutely tempted by greed and fame and lust.

More study and more teaching led to more fame, and further into the whirlpool he went. He took a mistress, to whom he was faithful for the next fifteen years. Together they had a son, Adeodatus. As with Thagaste and Madaura before, now Carthage seemed too small for Augustine, so he and his mistress and son sailed to the largest city of the empire, Rome. No sooner did he arrive than another wave of disillusionment and disappointment whelmed him. This is like the classic case of the standout college athlete’s not having a stellar debut game in the pros. So Augustine, ever the wanderer, retreated to Milan to get his footing.

As he wandered literally across the cities of the Roman Empire, he also wandered over the worldviews and philosophies of his day. He was running from God. He was soon caught in the grip of Manichaeism, a distant form of Platonism that added some elements of Christianity (deeply distorted) and of the mystery religions from the various lands that Rome conquered. Augustine was particularly occupied with the question of the nature and origin of good and evil. His mind was restless.

light

In a garden by a fountain in Milan, something very unexpected happened in the life of Augustine. Four things led up to the moment. First, one of Augustine’s friends died. Augustine tells us of many of his friends throughout The Confessions, but this one remains nameless, as if naming him were too sorrowful for Augustine. The second thing concerned his mother. As Augustine wandered, Monica followed close behind. She, too, had come to Milan. Throughout Augustine’s life, she never stopped praying for her son’s salvation, and she never wavered in her belief that God could save him. Third, Augustine heard the preaching of Ambrose. Augustine had “tried” Christianity but found it rhetorically unsatisfying. But then he heard the persuasive and compelling preaching of Ambrose. This led Augustine to read the New Testament. The fourth thing that happened concerned his quest for happiness and the fulfillment of his deepest longings and desires. The more he pursued happiness, the more unhappy he felt. The more he pursued fulfillment, the more empty he felt. He was a ship pulling into all the wrong ports. In the first paragraph of The Confessions, he pens the classic line “Our hearts are restless, until they find their rest in You.”

And so he was in a garden with his friend Alypius. He had a copy of Paul’s epistle to the Romans with him, and he heard what he could swear sounded like children singing in a game, “Tolle, lege. Tolle, lege.” “Take up, read. Take up, read.” And so he read Romans, and suddenly, light flooded his soul and drove the darkness and doubt away. Augustine found what he had been looking for: truth, joy, life, happiness, and peace. His restless heart found rest.

As Augustine himself would come to teach, however, he did not find God; God found him. Consequently, there is a fifth and ultimate element to the story of Augustine’s conversion in Milan in 386. As Augustine thought he was wandering from God, “the Hound of Heaven,” as Augustine calls God in his Psalms commentary, was all the while bringing Augustine to Himself. The story of Augustine’s life is the triumph of the grace of the sovereign God. As human actors play out their lives, God sovereignly governs all human affairs, bringing all things to the fulfillment of His eternal decrees and purpose, as an accomplished archer sends the arrow to the very middle of the bull’s-eye.

Right after Augustine’s conversion, he and some friends went to Cassiacum, a resort town nestled near the foot of the Italian Alps. There Augustine, a new Christian, wrote his first Christian books (Augustine had written many books before his conversion on a range of subjects, but they are all lost to history). The second of these books is a short dialogue titled On the Happy Life. Like Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave” or Voltaire’s “The Story of a Good Brahmin,” this text explores the basic question of happiness and how to attain it. Augustine says that few ever do. But those who do attain happiness, like him, know this: “Whoever is happy has God.” He adds that having God is thoroughly enjoying God.

Augustine returned to Milan and was baptized by Ambrose in the spring of 387, along with Adeodatus and Alypius, and immediately planned to return home. Augustine dismissed his mistress rather than marrying her, an act that he later regretted. He kept his son with him. They, along with Monica, arrived in Ostia, the port city that served the city of Rome, rented rooms overlooking a courtyard, and awaited passage back to Carthage. There in Ostia, Monica died, and “a great wave of sorrow surged” into Augustine’s heart. The episode, found in book 9 of The Confessions, is one of the most touching moments that Augustine records.

bishop

While Augustine was in Thagaste in 389, Adeodatus, who had gone to Carthage to study, died. Augustine devoted his energies to writing and was ordained in 392 in Hippo Regius in modern-day Algeria. In Augustine’s day, it was the capital of the region. It had a theater that could seat six thousand people and all the trappings that one found in ancient Roman cities. This city also had a large basilica. Four years after becoming a priest, Augustine was appointed bishop of Hippo Regius.

As bishop, Augustine oversaw church councils; spoke into all the controversies of his day; offered spiritual counsel to many people, including generals and Roman officials; visited churches across his diocese; settled disputes; and even had a hand in fundraising, raising money for church construction projects. He also, as mentioned, preached often. Hippo’s basilica measured nearly half a football field long. The roof consisted of wood beams covered in terra-cotta tiles. Mosaics covered the floor, and the apse was made of marble native to the region. Standing between the altar and the nave was a large masonry structure from which Augustine preached.

Augustine settled all manner of disputes. In one case, at a library, the priests charged with copying manuscripts were distracted all day long by others who wanted to “check out” the other manuscripts in the collection. They were too busy being librarians to focus on their work as scribes. Augustine applied common sense. Let there be one fixed hour of the day to check out books; otherwise, leave the scribes alone.

Such matters were the “little foxes” that took up Augustine’s time. The big matters were the two major controversies of Donatism and Pelagianism. The Donatist controversy stretches back to the first decade of the fourth century and the time of intense persecution leading up to Constantine’s becoming the Roman emperor. After Constantine’s legalization of Christianity alleviated the persecution, those who compromised their faith during times of persecution were side by side in the pews with those who remained faithful and consequently suffered during the persecution. The conflict was keenly felt, especially so at Carthage and across northern Africa. Over the decades, issues of tradition, church membership, the nature of apostasy, and the nature of salvation itself all became bound up in Donatism.

Pelagianism gets to the heart of the gospel. Pelagius left Britain for Rome around 380. Around 400, he entered the discussion of morality and the transmission of sin. Pelagius wanted to hold people morally accountable and could see doing so only by teaching that Adam’s sin is not imputed to his progeny. For Pelagius, Adam is an example. The upshot is that people are not born sinful but are born neutral. We are free to choose good and God or to choose the opposite direction. Augustine countered the heresy of Pelagius by championing the grace of God. We are born sinful, not neutral. Augustine introduced the expression non posse non peccare, meaning that we are not able not to sin. To put it another way, we are bound to sin. Then Augustine declared, “Nothing sets free save the grace of God through Jesus Christ.” We do not cooperate with God’s grace in our unregenerate state. We do not make the first steps toward God. We are bound to sin and dead in sin. But God in grace sent His Son and regenerates us and gives us the gift of faith.

In a letter from 426, Augustine notes that if the grace of God is bestowed according to our merits, we get at least some of the glory in salvation. In Pelagianism, the glory is not for God alone, but there is glory for man also. Augustine simply declares that Scripture forbids any such notion. We have received everything from God, especially our salvation, and to Him alone belongs the glory. Despite Augustine’s clear refutation, Pelagianism persisted into the fifth century and beyond.

Augustine led the charge in these battles, but he was not alone. Augustine remained friends with Alypius this entire time. They were converted together, were baptized together, were ordained together, and served in neighboring dioceses. Augustine often quoted Cicero’s definition of friendship: “Friendship is agreement with kindliness and affection, on things human and divine.” Augustine and Alypius had been friends in things human, and then, in Christ, they were friends in things divine. Augustine believed that the kind of friendship he had with Alypius and with several others was a further gift that stemmed from God’s gift of salvation. Augustine clearly towered over his peers, and many of his friends and brothers in arms during times of controversy and crisis are names lost to us. Nevertheless, Augustine knew that he was not alone and that he was buoyed by others.

crisis

Augustine wrote around four hundred books of varying length. Many are classics. Two are monumental: The Confessions and The City of God. Augustine wrote The Confessions in 400. He started The City of God in 412 and finished thirteen years later. The City of God came out of a crisis that would dominate the last two decades of Augustine’s life—namely, the sack of Rome and the subsequent fall of the western Roman Empire. Alaric, the Visigoth king, sacked Rome in 410. This caused widespread panic. Few in the West could imagine life without the Roman Empire, and many could not imagine the church without the structure and support of the Roman Empire. Others blamed Christianity for Rome’s defeat and the fall of the empire. Everywhere Augustine looked, he saw faulty thinking. He was above all a teacher, and so he wrote The City of God to teach the church a better way to think about the apparent crisis.

Augustine begins with the glorious city of God, the city or kingdom of which there is no end. It alone is eternal, abiding, and true. Then there is the city of man, which prefers its own gods. There has always been a contest between these two cities. Nations and empires come and go, but the conflict remains, and victory and supremacy belong to the city of God alone. With the Roman Empire in mind, Augustine writes on the very first page of “all earthly dignities that totter on this shifting scene.” Nations and worldviews and ideologies all totter and shift and, eventually, collapse.

Augustine wrote the final pages in 425. He was feeling his age, and his thoughts turned to heaven. He wrote of the great felicity that will be there, how we will be untainted by sin and pure, and how God will be fully all in all. There we will enjoy true beauty, and all our longings and desires will be fully satiated. Augustine called heaven a place of holy eternal rest (sanctum aeternum otium), where we will be still and know that God is and we will be with Him in His city.

By 430, the Vandals were laying siege to the city of Hippo. Augustine orchestrated the city’s final defenses from his deathbed. As he weakened, his faithful scribes wrote out the Psalms in large letters for him to read. When he could no longer hold the pages, they pasted them to the walls. No longer on the run, Augustine had far more than he ever needed or desired, for he had God, who is all in all.

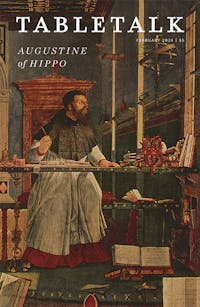

Detail from Vices and Virtues on Earth, from ‘De Civitate Dei’ by St. Augustine of Hippo (354-430), Bridgeman Images