Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

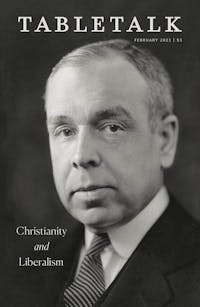

Contrary to the claim of modernists, the historic Christianity that J. Gresham Machen defended was not individualistic. Christianity “fully provides for the social needs of man,” he wrote in chapter 5 of Christianity and Liberalism, and he ended that chapter with reflections on the social consequences of salvation: the gospel transforms human institutions, including families, communities, the workplace, and even government.

But Machen was not finished. What remains is the highest and the most important institution of all—the church of Christ. Indeed, the entire thesis of Christianity and Liberalism comes to bear on the final chapter as Machen urges the recovery of a high view of the church. Judging from the current state of the church even among those who claim to love this book, however, we may wonder how many have carefully read this final chapter.

Machen begins by challenging a thin form of community that is premised on the “universal brotherhood of man.” Clear doctrinal boundaries are required to sustain a genuine fellowship of brothers and sisters in Christ, simply because, as he clearly demonstrated in the preceding pages, liberalism is a complete departure from Christianity. “The greatest menace to the Christian Church today,” he wrote, “comes not from the enemies outside, but from the enemies within; it comes from the presence within the church of a type of faith and practice that is anti-Christian to the core.” Consequently, “a separation between the two parties in the church is the crying need of the hour.” Machen’s “straightforward” and “above board” appeal earned him the respect of “friendly neutrals” (as the secular journalist H.L. Mencken described himself as he followed the debate closely).

How would this separation take place? At the time the book was published, what seemed the most likely prospect—from both sides of the divide—was that a small number of liberals would leave the church. And Machen invited them to take this step of honesty. But he also anticipated another scenario, wherein conservatives would be forced to leave the church. A decade later, this is how the struggle would play out, as he himself was defrocked for the high crime of “disloyalty” to the boards of the church that were beset with modernism. Faithfulness to their ministerial calling compelled him and his allies to bear this cross.

Countervailing appeals to preserve the unity of the church obscured the issues that Machen laid out, and such ecclesiastical pacifism provided neither lasting peace nor unity: “Nothing engenders strife so much as a forced unity, within the same organization, of those who disagree fundamentally in aim.” Tolerance of doctrinal deviation is “simple dishonesty.”

Machen anticipated another option: some ministers might gravitate toward a functional independence, finding contentment in the orthodoxy of their own congregations or the soundness of their presbyteries. But, he countered, this was simply not a Presbyterian option. Presbyterians must commit themselves to the corporate witness of the church. The voice of every pulpit in the church is the voice of the whole church. So all officers of the church are responsible for the proclamation from all its pulpits.

Machen’s ecclesiology sought to distinguish a genuine communion of saints from its counterfeits. There is no communion in life where there is no communion in thinking. Doctrinal indifference breeds the very broad churchism that allowed theological liberalism to enter the pulpits of the church. Only a “whole-hearted agreement” with the church’s doctrine, expressed in its confession of faith and catechism, can yield true Christian fellowship.

To establish and preserve this agreement, the church must diligently pursue four tasks. First, it must commit itself to the task of contending for the faith. Second, the church must take care in the ordination of its officers, holding to a high qualification for fitness to church office. Third, ruling elders must rule—that is, they must guard the preaching of the pulpit. Finally, the church must restore catechesis and other discipleship ministries to address the prevailing ignorance in the church pews. In a word, the church must steward its doctrine. It must be vigilant in propagating and defending that doctrine, even with militance and exclusivism.

Machen was not out to split the church. The liberals were in the process of doing that. He pursued its unity in the only sustainable way: by its clear separation from the world. A century later, we see Machen vindicated. Liberalism has become too much like the world, and thus mainline Protestantism is losing meaning and members in drastic numbers.

What about the evangelical church in America? Has it maintained its militance or its corporate witness to the world? The emphasis on religious experience and indifference to doctrine has had its effect in many quarters of American evangelicalism where we find relaxed confessional commitments, the demise of catechesis, and reluctance to pursue church discipline. Is it any wonder that commitment to and weekly attendance in church has diminished for many professing Christians as a priority for the Christian life? We now feel free to join and leave churches based on our taste and preferences. Or even worse, we jettison the church entirely in our individual pursuits of religious authenticity. Churches today have all too willingly accepted these terms, and rather than contend against the worldliness of their age, they have desperately sought to market themselves to satisfy the whims of religious consumers. To an age obsessed with authenticity, Machen offers the timely reminder that the test of authenticity of the church in our or any other age is its display of the marks of the true church: the preaching of the Word, pure administration of the sacraments, and exercise of church discipline.

The abiding value of Machen’s Christianity and Liberalism will be lost on those who fail to give his last chapter a careful study. A church that locates its calling in the flourishing of an individual’s personal religious experience is one that has succumbed to worldliness. Machen directs us instead to see the church’s calling as stewarding the doctrine found in the Word of God and summarized in its confessional standards. This becomes a place of belonging for pilgrims who have renounced worldliness in their march toward their heavenly home, a place that provides the hope on which Machen concludes his book.

Is there no refuge from strife? Is there no place of refreshing where a man can prepare for the battle of life? Is there no place where two or three can gather in Jesus’ name, to forget for the moment all those things that divide nation from nation and race from race, to forget human pride, to forget the passions of war, to forget the puzzling problems of industrial strife, and to unite in overflowing gratitude at the foot of the Cross? If there be such a place, then that is the house of God and that the gate of heaven. And from under the threshold of that house will go forth a river that will revive the weary world.