Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

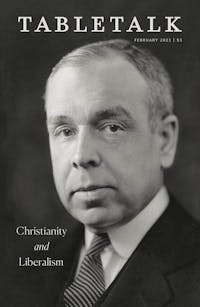

One of J. Gresham Machen’s emphases in Christianity and Liberalism is the need to understand Jesus rightly. As a devoted churchman and astute scholar, Machen was well informed about unorthodox views of Jesus both in the church and in the academy, and the same errors often arise in our own day. Today, Jesus is often spoken of in scholarly literature as a Jewish prophet from Nazareth who was also, in some respect, the Son of God—but this is not always understood as the divine Son of God. It is often assumed that Jesus of Nazareth was a human person about whom we can say much, whereas to speak of Him as the divine Son of God would be too speculative. But here we must be careful, for orthodox Christology warns that it would be quite mistaken to think of Jesus simply as a person from Nazareth. At the same time, it would also be wrong to deny the true humanity of Jesus, which is also a nonnegotiable for orthodox Christology. To navigate these tricky waters requires us to articulate the doctrine of Christ appropriately.

Thankfully, we have many hundreds of years of faithful, biblical reflection in the church’s great creeds to draw upon to help us think rightly about Christ. To begin, we must understand that to speak of Christ is to speak of the second person of the Trinity: the eternal Son of God. It is this divine Son of God, this divine person, who is the person we encounter in the incarnation. It would therefore be incorrect to speak of Jesus Christ as if we were encountering a human person from Nazareth. It would also be incorrect to think of two persons in the incarnation—as though in the incarnation we met both a divine person and a human person. Instead, Jesus Christ is one person—a divine person who has taken on a human nature. Though He was born in Bethlehem and raised in Nazareth according to His human nature (Matt. 1:18–23; Luke 2:1–14), His true origins are eternal (see Mic. 5:2), for He is the eternal Son of God.

This requires us to understand rightly what is often known as the hypostatic union (see Westminster Confession of Faith 8.2). The hypostatic union teaches that in the incarnation, two natures (divine and human) are united in the one person of Christ. The term hypostasis (from which the term hypostatic comes) refers to a divine person, and union refers to the union of the divine and human natures in the one person. This means that in the incarnation, Christ retains His divine nature while also taking on (or assuming) a human nature. Yet these natures are not in any way confused, changed, divided, or separated, but they are united in the one person of Christ. Neither do the natures act on their own, but it is always the person of the Son of God who acts. This reflects an important Christological principle: persons act; natures do not.

Further, the one person of Christ acts according to what is proper to each nature. Thus, in the incarnation the Son of God continues to be what He has always been (divine) but takes on a true human nature for us and for our salvation. In the hypostatic union, we speak of the Christ who is both truly God and truly man, though He remains one person.

Perhaps it is not surprising that the hypostatic union has not always been rightly affirmed. Several heresies illustrate the wrong way to think of Christ. Arianism taught that the Son of God was not fully divine in the same way as the Father is divine. But this misses the clear biblical teaching of the full divinity of Jesus (e.g., John 1:1; 20:28; Heb. 1:8; 1 John 5:20). Further, there is no in-between when it comes to divinity: either Jesus is divine or He is not. Other heresies taught that Jesus was not fully human. For example, Apollinarianism taught that Jesus did not have a human mind. But this would make Jesus less than human, and He would thus not be qualified to be the Savior of humanity, for we all have sinful minds that need redemption. Eutychianism argued that in Christ the divine and the human natures are somehow mixed together into a third thing—some sort of combination of the divine and human. But this would also mean that Jesus would not have a human nature like ours, and this view is therefore to be rejected (see Heb. 2:14–18). Another heresy that continues to rear its head is Nestorianism. This erroneous view, which was countered by Cyril of Alexandria and the Council of Ephesus in AD 431, teaches two persons in Christ. But orthodox Christology teaches that Christ is one person.

Machen understood why this is so important. In the Gospels, Jesus is concerned that His disciples know who He truly is, in contrast to the speculations of the crowds (Matt. 16:13–17). Jesus is the Christ, the Son of the living God. The disciples clearly knew that Jesus was a man, but they also had to recognize that He was both Messiah and the divine Son of God. Elsewhere, Paul is concerned that we confess Jesus rightly (e.g., Phil. 2:6–11; 1 Tim. 3:16). Thinking and speaking rightly about Christ is a biblical concern for all Christians; it should not be abstract speculation only for theologians. As Machen wrote, “If Jesus was what the New Testament represents Him as being, then we can safely commit to Him the eternal destiny of our souls.”

Here’s why it matters: our Savior must be both truly God and truly man to save us from sin. Only one who is God can withstand the wrath of God against sin and grant us everlasting life (see Westminster Larger Catechism 38; Heidelberg Catechism 17). Yet only one who is man, who has the same nature as us, could bear the curse for our sins in the same nature that sinned in the beginning (see WLC 39; HC 16). Only Jesus is the perfectly obedient second Adam who overcomes the disobedience of the first Adam while never ceasing to be the eternal Son of God. There is no other name under heaven by which we must be saved, for only Jesus is the resurrected and glorified Lord of all, who is truly God and truly man.

The great creeds of the church speak of Christ as the second person of the Trinity who has come down to save us. He is not a man who became God but God who became man. This is a crucial difference with massive implications. To speak of Jesus primarily as a man or as if He were a human person in a way that the creeds do not denies something central to the gospel. Machen himself observed that the substitutionary atonement assumes the uniqueness of Christ’s person. Our estate of sin is so great that no mere man could ever pull us out of the depths of its quagmire. We do not need only a model or a teacher; we need a Savior. As Machen asserted, “Jesus is no mere example for faith, but the object of faith.” We do not need a mere man to save us, but we do need a true man to save us. We need one who is truly God and truly man. We need Jesus Christ. That was true in Machen’s day, and it remains true in our day.