Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

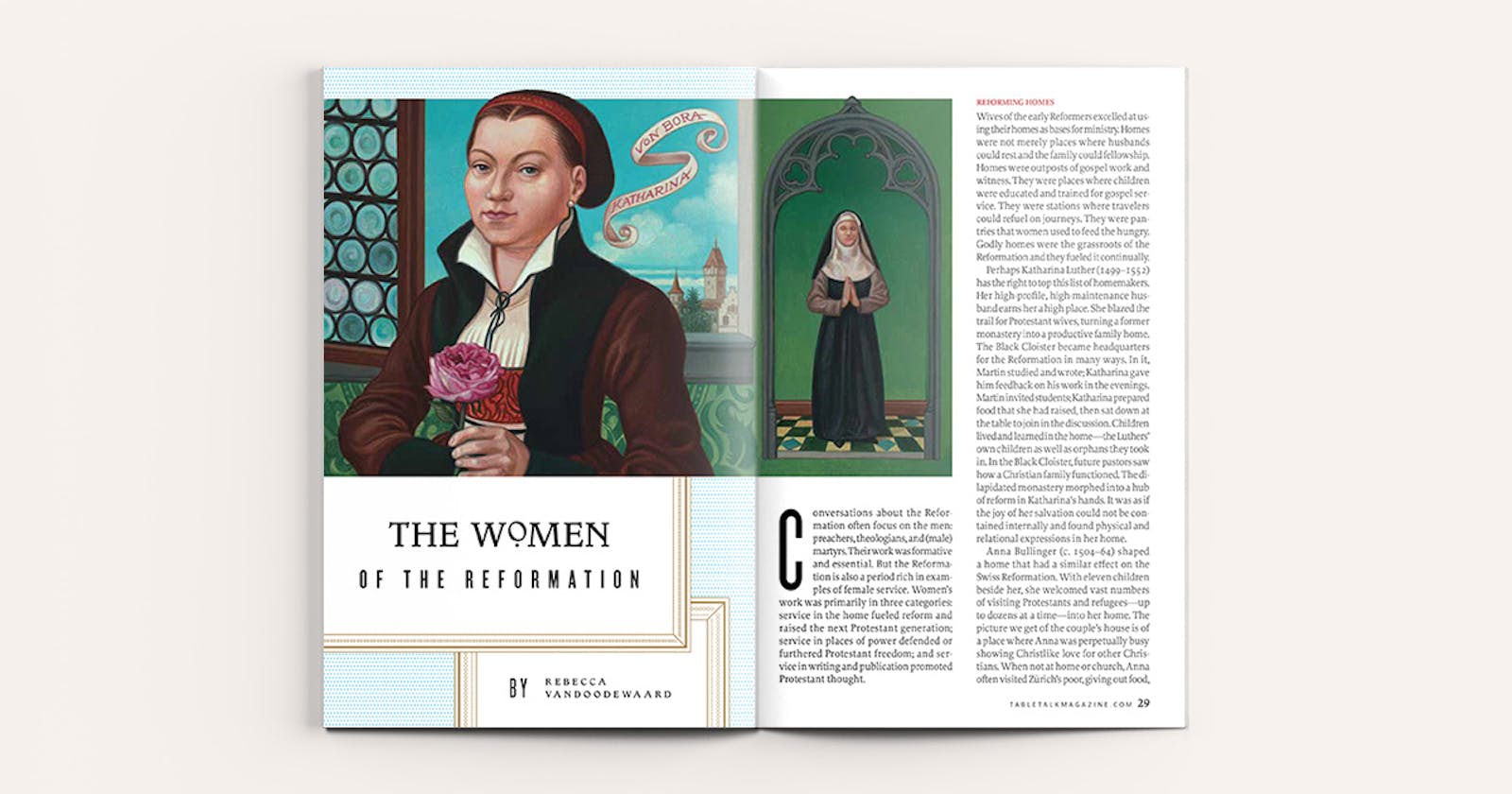

Conversations about the Reformation often focus on the men: preachers, theologians, and (male) martyrs. Their work was formative and essential. But the Reformation is also a period rich in examples of female service. Women’s work was primarily in three categories: service in the home fueled reform and raised the next Protestant generation; service in places of power defended or furthered Protestant freedom; and service in writing and publication promoted Protestant thought.

Reforming Homes

Wives of the early Reformers excelled at using their homes as bases for ministry. Homes were not merely places where husbands could rest and the family could fellowship. Homes were outposts of gospel work and witness. They were places where children were educated and trained for gospel service. They were stations where travelers could refuel on journeys. They were pantries that women used to feed the hungry. Godly homes were the grassroots of the Reformation and they fueled it continually.

Perhaps Katharina Luther (1499–1552) has the right to top this list of homemakers. Her high-profile, high-maintenance husband earns her a high place. She blazed the trail for Protestant wives, turning a former monastery into a productive family home. The Black Cloister became headquarters for the Reformation in many ways. In it, Martin studied and wrote; Katharina gave him feedback on his work in the evenings. Martin invited students; Katharina prepared food that she had raised, then sat down at the table to join in the discussion. Children lived and learned in the home—the Luthers’ own children as well as orphans they took in. In the Black Cloister, future pastors saw how a Christian family functioned. The dilapidated monastery morphed into a hub of reform in Katharina’s hands. It was as if the joy of her salvation could not be contained internally and found physical and relational expressions in her home.

Anna Bullinger (c. 1504–64) shaped a home that had a similar effect on the Swiss Reformation. With eleven children beside her, she welcomed vast numbers of visiting Protestants and refugees—up to dozens at a time—into her home. The picture we get of the couple’s house is of a place where Anna was perpetually busy showing Christlike love for other Christians. When not at home or church, Anna often visited Zürich’s poor, giving out food, clothes, and money when she could. She followed the example set by Anna Zwingli, whom she cared for after her husband, Huldrych, died in battle. Anna Bullinger herself set an example that became known through Europe, partly through her guests and partly through her husband’s writings on marriage and family life.

For a pastor’s wife in the Reformation era, opening one’s home and family to people who needed them was a public denunciation of monasticism. This biblical lifestyle directly challenged the tenets of the Roman Catholic Church’s teaching on clergy, marriage, and more, as well as proving that convents and monasteries were not needed: Protestant pastors’ wives could pray, read, garden, care for the sick, host travelers, and foster an intellectual climate just as well as monks and nuns had for centuries. Protestant housewives made monasticism obsolete. Though their work was not always visible, Protestant wives attacked Catholic presuppositions by their very domestic work, putting Rome on the defense. And their nurture of children raised a new generation of Protestants who were ready to stand on Scripture alone in the face of Roman Catholic persecution.

Reforming Authority

Queens and princesses had very public roles during the Reformation. A disproportionate number of royal women converted to Protestantism; they believed much more readily than their male relatives. And they were not following political trends, either. High-profile Protestants were often easily targeted. The same is true for high-ranking nuns: abbesses were often aristocratic, too, and created scandal by converting to Protestantism. While Reformers’ wives faced a staggering amount of work behind the scenes, Reforming queens and abbesses faced isolation, intimidation, and violence in the most public ways.

When her alcoholic and adulterous husband died in 1555, Jeanne d’Albret (1528–72) became queen of Navarre. Sandwiched between the two powerful nations of France and Spain, Jeanne was in a vulnerable position. This did nothing to slow or discourage her. Having made public profession of the Reformed faith years before, Jeanne, on her accession, labored successfully to bring reform to Navarre, making the country a safe haven in a sea of Roman Catholicism. Her children were kidnapped, her life was threatened, rebellions erupted, war broke out with France—her love for the church was greater than all of these. She called herself “a little princess” and believed that, like Esther, God had put her in her position to defend His people. Her work provided shelter for Huguenots during the French Wars of Religion. But she was also an example of faith under fire: her courage and doctrinal resolve were discussed internationally and brought comfort to other suffering believers.

Katharina von Zimmern (1478–1547) had a difficult childhood and was eventually placed in a convent. She and her sister were molested by priests and returned home. After a time, Katharina was returned to the convent for good, eventually becoming the imperial abbess of Zürich. In this position, she controlled huge amounts of land, cash, and people—Rome was fat and generous in its appointments. But like Zürich itself, Katharina was exposed to the Reformed faith and at some point converted. She invited Protestant ministers to teach the nuns Latin and provide spiritual care. Zwingli knew how powerful the abbess was; she could have exposed Protestant activity and asked Rome for backup. Instead, at the end of 1524, Katharina signed over the abbey and all of its assets to the city of Zürich. This was personal conviction—peaceful but strong—that Rome was wrong and must be resisted. The transfer of property gave the city an advantage that was more than economic: it made Zürich an openly free and safe place for Protestants without the civil war that so many other places endured. Yet, it placed Katharina in a very vulnerable position as Rome’s open enemy. God protected her, also providing a husband and daughter. And Katharina’s public leadership did not end there. Later, she served on the city council.

Katharina and Jeanne were not the only female political and religious leaders to convert. God used Roman Catholic royal families and corrupt systems of church government to exhibit the futility of fighting truth. The gates of Rome were not prevailing against the church militant.

Reforming Pens

The third major way that women contributed to the Reformation was by writing. It may seem like a modern thing to do, but even in the medieval era, a few women wrote and published. With its emphasis on education and literacy, the Reformation fostered many Protestant female authors.

Religious poetry was the dominant genre for women in the pre-Reformation era. Protestant women did not discard this tradition; they redeemed it. Marguerite de Navarre (1492–1549) was Protestantism’s first published female poet. From her initial Roman Catholicism to recognizable Calvinism, Marguerite’s poetry reflects her spiritual journey. But beyond being personal records of devotion, these poems were publicity for Reformed doctrine. Marguerite’s last major work emphasizes and wonders at Christ’s all-sufficient, complete work for His people. In publishing it, she challenged Rome’s teaching on saints, indulgences, penance, and the Mass. It was a public proclamation of salvation by grace alone through faith alone.

Women also wrote overtly theological Protestant works. The first known one was a defense of clerical marriage against the Roman Catholic teaching on celibate clergy. It was Katharina Zell’s (1497–1562) very personal defense of her priest-husband. The couple was under attack for being married against canon law, but Katharina pointed out that if the pope didn’t have a problem taxing prostitution among the clergy, then he really had no argument against a faithful marriage. Drawing on Scripture to back her argument, Katharina made a taboo issue part of constructive public conversation, removing much of the stigma that remained for married priests.

Memoirs later became popular as well. Charlotte de Mornay’s (1550–1606) account of her husband’s life made him better known throughout Europe. His example of hard work, faithfulness, and lack of bitterness through suffering was strong encouragement to other oppressed believers.

There were many more women in this era, some writing for personal growth and recreation but many publishing for the sake of the emerging Reformed church. Their obvious intellectual ability matched Protestantism’s belief that brains should be used, whether they be male or female. It also gave confirmation to the Protestant mothers who were working to educate the next generation of Reformed women that their work was not a waste. They were providing necessary training for women who would raise the next generation of mothers, authors, preachers, and queens.

It is easy to skim through these stories, classing different lives into places we can see them best. Reality was more complex. Some women served in all three areas; others excelled in one. Their impact was tremendous because the Savior they served is omnipotent. These women loved Jesus and served Him because He loved them. And because Jesus still loves women today, we can expect them to continue serving the church in formative ways.