Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

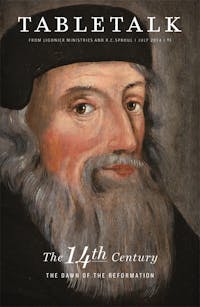

On February 28, 2013, Pope Benedict XVI abdicated the papacy. Six days later, Jorge Mario Bergoglio, a Jesuit priest and archbishop of Buenos Aires, was elected by the College of Cardinals and installed as Pope Francis I, bringing to a conclusion a remarkable series of events. The papal resignation and Francis’ accession takes us back to the last pope to abdicate, Gregory XII (1415), and the marvelously messy history of the Avignon Papacy.

OF POPES AND ANTIPOPES

If we believe the popular myth, we might think that there has been an unbroken succession of popes in Rome since Peter. But according to Roman Catholic scholars, there have been no fewer than forty-six “antipopes” in the history of the papacy, and in the early fifteenth century there were no fewer than three popes ruling simultaneously. How we number the antipopes depends, of course, on when we consider the papacy actually to have begun. Even if we begin with Gregory I (reigned 590-604), the number of antipopes is smaller but still impressive. One Roman Catholic writer defines antipope as “any person who took the name of pope and exercised or claimed to exercise his functions without canonical foundation.” That means that an antipope is anyone who ever claimed to be a pope but whom Rome does not now recognize as a pope.

One reason traditionalist Roman Catholic scholars resort to this approach is the Avignon Papacy. From 1305 to 1378, the papacy relocated to Avignon, France (about 425 miles southeast of Paris), and from 1378 to 1415, there were two and sometimes three popes, one of whom was in Avignon. In 1370, Pope Gregory XI attempted to return the papacy to Rome, if only to reassert papal and Roman control of the Italian peninsula. Upon his death in 1378, the problem of antipopes intensified with the election of Urban VI (reigned 1378-89) in Rome. He was so unpopular with the people that the cardinals lied about whom they had elected. He was also unpopular with some of the cardinals because he was said to have a temper and, most outrageously, because he accused the cardinals of living ostentatiously—which was a true charge. In retaliation, some electors accused him of insanity.

In reaction to Urban’s election, some of the papal electors relocated to Avignon, where the papacy had been since 1305 (except between 1328 and 1330, when there was a competing pope in Rome). There they elected Cardinal Robert of Geneva as Clement VII (reigned 1378-94). There followed a succession of popes and antipopes in Rome and Avignon between 1378 and 1409, when things took an even stranger twist.

THE CRISIS DEEPENS

In 1409, the Council of Pisa, with cardinal bishops in attendance, deposed the Avignon pope, Benedict XIII (reigned 1394-1415), and the Roman pope, Gregory XIII (reigned 1410-15), and elected Alexander V (reigned 1409-10). This move failed, with the result that there were now three competing popes. To further complicate matters, Alexander V’s tenure in office was very brief. He was succeeded by John XXIII (reigned 1410-15). Each of the “popes” had excommunicated the others and their followers so that all of Western Christendom at that point was excommunicated.

At the Council of Constance (1414-18), Pisan Pope John XXIII was arrested, brought to Constance, and imprisoned. The Roman Pope Benedict XIII was deposed, and Avignon Pope Gregory XII abdicated. The council elected Odo Colonna as Pope Martin V on November 11, 1417, ending the schism. Rome has never pronounced on the canonicity of Urban VI’s election or the legitimacy of the Council of Pisa.

Needless to say, these events produced uncertainty that provoked grave doubts among honest, fair-minded Christians in the late medieval period. Concerns regarding the visible head of Christ’s church and the conduct of post-Avignon popes combined to undermine the credibility of the papacy through the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

TENUOUS CLAIMS

Like Christians during the Avignon crisis, we live in an age when authority and order seem to be dissolving before our eyes. Some Christians, who are sensitive to these cultural shifts and to their effect upon evangelical churches, see the problems reflected in liturgical changes and general spiritual and ethical chaos. They are thus attracted to Rome on the basis of her claim to continuity with the past, ostensible unity, and stability.

The Avignon crisis is just one of many examples from the history of the medieval church that illustrate the futility of seeking continuity, unity, and stability where they have never existed. The historical truth is that the Roman communion is not an ancient church. She is a medieval church who consolidated her theology, piety, and practice during a twenty-year-long council in the sixteenth century (Trent). Her rituals, sacraments, canon law, and papacy are medieval. The unity and stability offered by Roman apologists are illusions—unless mutual and universal excommunication and attempted murder count as unity and stability. Crushing opponents and rewriting history to suit present needs is not unity. It is mythology.

Roman apologists sometimes seek to vindicate the Roman popes, as distinct from the Avignon popes and the Pisan popes, by describing the Avignon popes as if they were less fit for office than the former. That is, to put it mildly, a strange argument. If popes are as popes do, then we may shorten the list of popes quite radically. On that principle, Rome had no pope from 1471 to 1503, and arguably beyond. In that period, Sixtus IV (reigned 1471-84), in an attempt to raise funds, extended plenary indulgences to the dead. Innocent VIII (reigned 1484-92) fathered sixteen illegitimate sons, of whom he acknowledged eight. Alexander VI (reigned 1492-1503) fathered twelve children, openly kept mistresses in the Vatican, made his son Cesare a cardinal, and tried to ensure Cesare’s ascension to the papacy. Alexander’s daughter Lucretia has been alleged to be a notorious poisoner. We have not even considered Julius II (reigned 1503-13), who took up the sword and was so busy conducting military campaigns to improve papal control over the peninsula that he conducted Mass while wearing armor.

The existence of simultaneous popes in Rome, Avignon, and Pisa, each elected by papal electors and some later arbitrarily designated as antipopes, illustrates the problem of the notion of an unbroken Petrine succession. The post-Avignon papacy is an orphan who has no idea who his father was in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

UNBIBLICAL INNOVATIONS

As happened upon the elections of Benedict XVI and John Paul II to the papacy, reporters stood in Vatican Square after Francis’ election and announced in sonorous tones that the new pope was the successor of Peter and marked another link in an unbroken chain of succession dating back to the first century. With each papal inauguration, reporters stand before sixteenth-century buildings to create the impression that the Apostle Peter held court in them two thousand years ago, that white smoke has always risen over the Sistine Chapel to signal a papal election, and that cardinal bishops have always emerged from the conclave after electing a pope.

In fact, none of these features is Apostolic or even patristic. As one Roman Catholic scholar concedes, “In fact, wherever we turn, the solid outlines of the Petrine succession at Rome seem to blur and dissolve.” It was Damasus I (reigned 366-84), who first asserted the title pope (from the Latin papa, “father”) for the bishop of Rome, and there was nothing remotely like the papacy as we know it until Gregory I (reigned 590-604). The papacy as we know it is a medieval creature. The Vatican did not begin to come into existence until 1506. To be sure, there has been a church on Vatican Hill since the fourth century, but there has not even been a continuous history of papal attendance in Saint Peter’s. The papal headquarters did not move to Vatican Hill until after the Avignon Papacy, and the conclave of cardinals that we witnessed in March 2013 did not exist until the eleventh century.

Our Protestant forebears were deeply skeptical of the papacy as an institution—for good reason. The resignation of Pope Benedict XVI reminds us that the papacy is a purely human institution without divine warrant, and that it has a complicated history. Claims to an unbroken succession crash on the rocks of history, especially those great rocks cropping up at Avignon, Pisa, and Rome for a century in the late medieval period.