Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

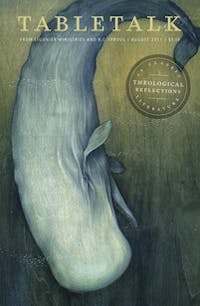

It seems that every time a writer picks up a pen or turns on his word processor to compose a literary work of fiction, deep in his bosom resides the hope that somehow he will create the Great American Novel. Too late. That feat has already been accomplished and is as far out of reach for new novelists as is Joe DiMaggio’s fifty-six-game hitting streak or Pete Rose’s record of cumulative career hits for a rookie baseball player. The Great American Novel was written more than a hundred and fifty years ago by Herman Melville. This novel, the one that has been unsurpassed by any other, is Moby Dick.

My personal copy of Moby Dick is a leather-bound collector’s edition produced by Easton Press under the rubric “The Hundred Greatest Books Ever Written.”

Note that the claim here is not that Moby Dick is one of the hundred greatest books written in English, but rather that it is one of the hundred greatest books written in any language.

Its greatness may be seen not in its sometimes cumbersome literary structure or its excursions into technicalia about the nature and function of whales (cetology). No, its greatness is found in its unparalleled theological symbolism. This symbolism is sprinkled abundantly throughout the novel, particularly in the identities of certain individuals who are assigned biblical names. Among the characters are Ahab, Ishmael, and Elijah, and the names Jeroboam and Rachel (“who was seeking her lost children”) are given to two of the ships in the story.

In a personal letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne upon completing this novel, Melville said, “I have written an evil book.” What is it about the book that Melville considered evil? I think the answer to that question lies in the meaning of the central symbolic character of the novel, Moby Dick, the great white whale.

Melville experts and scholars come to different conclusions about the meaning of the great white whale. Many see this brutish animal as evil because it had inflicted great personal damage on Ahab in an earlier encounter. Ahab lost his leg, which was replaced by the bone of a lesser whale. Some argue that Moby Dick is Melville’s symbol of the incarnation of evil itself. Certainly this is the view of the whale held by Captain Ahab himself. Ahab is driven by a monomaniacal hatred for this creature, this brute that left him permanently damaged both in body and soul. He cries out, “He heaps me,” indicating the depth of the hatred and fury he feels toward this beast. Some have accepted Ahab’s view that the whale is a monstrous evil as that of Melville himself.

Other scholars have been convinced that the whale is not a symbol of evil but the symbol of God Himself. In this interpretation, Ahab’s pursuit of the whale is not a righteous pursuit of God but natural man’s futile attempt in his hatred of God to destroy the omnipotent deity. I favor this second view. It was the view held by one of my college professors—one of the five leading Melville scholars in the world at the time I studied under him. My senior philosophy research paper in college was titled “The Existential Implications of Melville’s Moby Dick.” In that paper, which I cannot reproduce in this brief article, I tried to set forth the theological structure of the narrative.

I believe that the greatest chapter ever written in the English language is the chapter of Moby Dick titled “The Whiteness of the Whale.” Here we gain an insight into the profound symbolism that Melville employs in his novel. He explores how whiteness is used in history, in religion, and in nature. The terms he uses to describe the appearance of whiteness in these areas include elusive, ghastly, and transcendent horror, as well as sweet, honorable, and pure. All of these are descriptive terms that are symbolized in one way or another by the presence of whiteness. In this chapter Melville writes,

But not yet have we solved the incantation of this whiteness, and learned why it appeals with such power to the soul; and more strange and far more portentous—why, as we have seen, it is at once the most meaning symbol of spiritual things, nay, the very veil of the Christian’s Deity; and yet should be as it is, the intensifying agent in things the most appalling to mankind. Is it that by its indefiniteness it shadows forth the heartless voids and immensities of the universe, and thus stabs us from behind with the thought of annihilation, when beholding the white depths of the milky way? Or is it, that as in essence whiteness is not so much a colour as the visible absence of colour; and at the same time the concrete of all colours; is it for these reasons that there is such a dumb blankness, full of meaning, in a wide landscape of snows—a colourless, all-colour of atheism from which we shrink?

He then concludes the chapter with these words: “And of all these things, the albino whale was the symbol. Wonder ye then at the fiery hunt?”

If the whale embodies everything that is symbolized by whiteness—that which is terrifying; that which is pure; that which is excellent; that which is horrible and ghastly; that which is mysterious and incomprehensible—does he not embody those traits that are found in the fullness of the perfections in the being of God Himself?

Who can survive the pursuit of such a being if the pursuit is driven by hostility? Only those who have experienced the sweetness of reconciling grace can look at the overwhelming power, sovereignty, and immutability of a transcendent God and find there peace rather than a drive for vengeance. Read Moby Dick, and then read it again.