Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

Hebrews 12 approaches the vast changes to come in church and culture as orchestrated by God for the advancement of His kingdom of grace: “‘Yet once more I will shake not only the earth but also the heavens.’ This phrase, ‘Yet once more,’ indicates the removal of things that are shaken — that is, things that have been made — in order that the things that cannot be shaken may remain” (vv. 26–27).

Periods of change, at times dizzying and violent, are providentially ordained by God for the advancement of His unchangeable, unshakeable kingdom. Changes in world culture, often accompanied by a literal “shaking down” of established institutions make way for something better, something that can never be shaken — the glorious reign of the crucified, risen Christ, of whom Isaiah says, “Of the increase of his government and of peace there will be no end” (Isa. 9:7).

As we attempt to keep our balance in the midst of the billowing surf of rapid change that is breaking upon us constantly, our attitude must be informed by the perspective of Hebrews 12 and Isaiah 9. With the serene plan of God in mind, we never have an excuse for panic or despair, even in the face of frightening shifts and disruptions in the economic and political systems where we have to live. This twenty-first century is, for instance, not an occasion for Christians to despair over the certainty of the Islamization of Europe. Philip Jenkins in God’s Continent argues that this grim scenario is very far from certain. Nor is it a time to wring our hands at the long-predicted, “inevitable” secularization of America. One could easily argue that current statistics actually point in another direction. A leading sociologist of southern American religion, Professor Samuel Hill, had predicted in the early 1960s (when he was my much-respected teacher) that evangelicalism in the south would be largely washed out by American secularism within the next thirty or forty years. But recently, in the 2000s, he has concluded that the precise opposite has happened: evangelical Christianity is even stronger in the southern states than it was forty years ago.

It is probable, though not yet certain, that the last 150 or so years have placed us among the four or five great “shakings down” of Western history since the incarnation of Christ some two thousand years ago. In AD 70, Jerusalem was shaken down by the Roman army, the old Jewish church-state system, which had in many ways hindered the expansion of the gospel, lost its major power. Its people were scattered, and many parts of the world were opened in a new way to the victorious mission of the Christian church.

Within four or five hundred years of Christian expansion, the powerful Roman Empire itself, which had once persecuted the church, and then nominally established Christianity, was also shaken down by its own corruption that made it impotent to stand against barbarian invasions. The downfall of a mighty centralized empire made way for the eventual rise of decentralized Christian kingdoms throughout much of eastern and especially western Europe. The central Roman state was no longer the key institution of Europe; it was for over a thousand years replaced by the Christian church. After the shaking down of Jerusalem, millions were brought to faith in Christ. After the shaking down of Rome, far more millions were won to Christ throughout Europe.

Alasdair MacIntyre, in his book After Virtue, identifies what happened: a world empire was functionally replaced by more local moral and civic communities: “A crucial turning point . . . occurred when men and women of good will turned aside from the task of shoring up the Roman imperium and ceased to identify the continuation of civility and moral community with the maintenance of that imperium. What they set themselves to achieve instead — often not recognizing fully what they were doing — was the construction of new forms of community within which the moral life could be sustained so that both morality and civility might survive the coming ages of barbarism and darkness” (p. 244).

Another massive shaking down of established institutions severely limited the control of western Europe by the Roman Catholic system after a thousand years of apparent hegemony. The Protestant Reformation burst forth like a tidal wave in Germany around 1520 and spread in nearly every direction. This shaking down came on the wings of religious revival, frequently accompanied by a resurgence of nationalism and hastened by the recent invention of printing. The gospel of salvation by the grace of God through faith in Jesus Christ came into ascendancy, causing the collapse in many lands of the medieval synthesis between sacramentalism and works-righteousness. The breaking of Roman Catholic unity wrought by earthly political structures within European Christendom made room for something truer to the gospel of Christ: a reformational return to the truths of Holy Scripture and the joyful deliverance of millions of souls from lack of assurance of salvation, which was part and parcel of the medieval penitential system.

I suspect that our Western culture is now once again in a time of massive shaking down “of things that can be shaken” in order that that which cannot be shaken may remain. The aftermaths of the earlier Industrial Revolution, followed by the more recent Information Revolution, and the radical unbelief of the various phases of the European Enlightenment have all come together and constituted the most severe challenge to Christianity in all its two-thousand-year pilgrimage. In addition to these emitters of deep shock waves, the early twenty-first century is in the beginnings of the breakdown of the once mighty nation state.

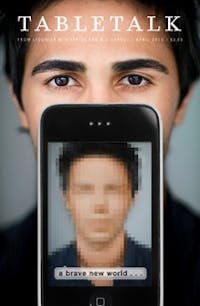

Ironically, it was rapid changes in technology that made possible the nation state, and it is also technology that is eroding its viability and relevance today. In Imagined Communities, Benedict Anderson maintains that the invention of printing and accurate timekeeping are what allowed the development of the modern nation state in the sixteenth century. But new technologies are leading to the irrelevance of the nation state. Dr. Jonathan Sacks, Chief Rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of Britain and the Commonwealth, shows us what is currently happening: “New forms of technology, especially information technology, fragment culture . . . [and] threaten the very existence of the nation state. . . . The new instantaneous global communication technologies are not marginal to how we live our lives. They affect the most fundamental ways in which we think, act and associate. . . . Information technology changes life systematically. It restructures consciousness; it transforms society. . . . The growth of computing, the modem, the mobile phone, the internet, email and satellite television will change life . . . . Ours is a transitional age” (The Home We Build Together [London: Continuum, 2007] 67–68).

What is perhaps most characteristic of what Alvin Tofler several years ago named as “future shock” is the sheer rapidity of the changes that make our heads swim. Tom Hayes and Michael S. Malone described this in a recent Wall Street Journal article as “The Ten-Year Century”: “Changes that used to take generations — economic cycles, cultural cycles, mass migrations, changes in the structures of families and institutions — now unfurl in a span of years.” They note that “when your computer hard drive becomes overwhelmed with too much information it is said to be fragmented — or “fragged.” Today, the rapid and unsettling pace of change has left us all more than a little, well, “fragged” (August 11, 2009, A17).

Yet the grand overarching viewpoint of Hebrews 12 on all change gives us hope. In all of history, instead of re

maining “fragged” and bewildered, we may face the unknown future with glad confidence and strong hands to take advantage of new opportunities for the spread of the gospel and the renewal of the culture on a more biblical basis. In all of the shakedowns we have surveyed — from Jerusalem to Rome to the end of medieval Catholic dominance — after every collapse of authority structures, there has been the advancement of something generally more Christ-honoring and humanly edifying. Old structures were shaken down to make room for the growth of the kingdom of God in Christ. Why should it be any different with the shaking down of our secularized nation states today? Their dominance will be replaced by something more amenable to the spread of the good news of Jesus Christ and the liberation of millions of men and women by the power of the Holy Spirit. What it will look like, we do not yet know, but we do know who is in charge!

The otherwise exhausting changes comprised in “the ten-year century” present the church with remarkable opportunities to offer something better to a “fragged” society. Let us speak of only one. The church should employ a classical response to the technologically based shift from “word to picture,” which has shortened people’s attention spans to as little as three minutes. Why not once again require our children to memorize parts of Holy Scripture and the catechisms of the church? That will do wonders to increase their ability to comprehend and concentrate in every area of truth. By returning to that and to the other biblical elements of worship and service, the church will always be ahead of the curve — a refuge for the fragmented and a mighty instrument of redemption and renewal as she moves in to inhabit the ground being vacated by the shaking down of things that can be changed by He who cannot be shaken nor changed.