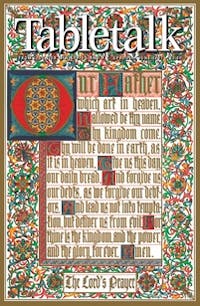

Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

The next time you attend a prayer meeting, pay close attention to the manner in which individuals address God. Invariably, the form of address will be something like this, “Our dear heavenly Father,” “Father,” “Father God,” or some other form of reference to God as Father. Not everyone customarily addresses God in the first instance in prayer by using the title “Father.” However, the use of the term Father in addressing God in prayer is overwhelmingly found as the preference among people who pray. What is the significance of this? It would seem that the instructions of our Lord in giving the model prayer, “The Lord’s Prayer,” is emulated by our propensity for addressing God as Father. Since Jesus said, “When you pray, say, ‘Our Father,’” that form of address has become the virtual standard form of Christian prayer. Because this form of prayer is used so frequently, we often take for granted its astonishing significance.

The German scholar Joachim Jeremias has argued that in almost every prayer that Jesus utters in the New Testament, He addresses God as Father. Jeremias notes that this represents a radical departure from Jewish custom and tradition. Though Jewish people were given a lengthy number of appropriate titles for God in personal prayer, significantly absent from the approved list was the title “Father.” To be sure, the Jews would use the term “Father” indirectly by addressing God as the Father of people, but never by way of a direct address, in which the person praying addressed God in personal terms as “Father.” Jeremias also notes that the serious reaction against Jesus by His contemporaries indicated that they heard in His addressing God as Father a blasphemous utterance by which Jesus was presuming, by this term of address, a certain equality that He enjoyed with the Father. Jeremias goes on to argue that there is no record of any Jew addressing God directly as Father until the tenth century a.d. in Italy, with the notable exception of Jesus. Though Jeremias’ findings have been challenged in some quarters, it remains a matter of record that Jesus’ use of the term “Father” in personal prayer is an extraordinary use.

Since the science of comparative religion reached its zenith in the nineteenth century and liberal theologians sought to reduce the core essence of all religion to the universal fatherhood of God and the universal brotherhood of man, it has followed from such liberal assumptions that to consider God as Father would be a most basic assumption in any religion. However, when we look again at the way in which the term functions in the New Testament and in the teaching of the apostles, we see that there is no doctrine of universal fatherhood of God in the Bible, except for His role as the creator of all men. Rather, the fatherhood of God has as its primary reference a filial (father/son) relationship that is restricted.

In the first and most important case, God has only one child, His only-begotten Son, the monogenēs, which restricts this filial relationship to Christ. We do not have the natural right to call God “Father.” That right is bestowed upon us only through God’s gracious work of adoption. This is an extraordinary privilege, that those who are in Christ now have the right to address God in such a personal, intimate, filial term as “Father.” Therefore, we ought never to take for granted this unspeakable privilege bestowed upon us by God’s grace. We note in the Lord’s Prayer that Jesus instructs us that now when we pray, we are to refer to God as “Our Father.” Again the “ourness” of this relationship is grounded in the unique ministry of Jesus by which, through adoption, He is our elder brother and He gives to us those privileges that by nature belong only to Him. Now, by adopting us, He says that we may regard God, not only as His Father, but as our Father.

The first petition of the Lord’s Prayer is found in the words, “Hallowed be Thy Name.” The opening address, “Our Father, who art in Heaven,” is simply that, an address. From that address, Jesus instructs His disciples to offer certain petitions in prayer. The first and chief of those petitions is that we pray that the name of God will be hallowed. This is also extraordinary in that as the prayer continues, we ask that the will of God be done on earth as it is in heaven and that His kingdom would come on earth as it is in heaven. Both of these desires can only be met when and if the God of the kingdom of heaven and of earth is treated with supreme reverence, honor, and adoration. When we fail to observe the third commandment, when we fail to honor God as God, and use His name as a curse word, or in a flippant, careless manner, we fail to fulfill this first petition. Perhaps nothing is more commonplace in our culture than the expression that comes from people’s lips on many occasions, when they say simply, “Oh, my God.” This careless reference to God indicates how far removed our culture is from fulfilling the petition of the Lord’s Prayer. It should be a priority for the church and for every individual Christian to make sure that the way in which we speak of God is a way that communicates respect, awe, adoration, and reverence. How we use the name of God reveals more clearly than any creed we ever confess our deepest attitudes towards the God of the sacred name.