Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

As a Reformed pastor, I am regularly confronted with questions about Reformed theology. Sometimes I am asked to explain a particular point of Reformed theology, and sometimes I am asked simply to explain what Reformed theology is.

Depending upon who is asking the question, and, perhaps more importantly, in what tone the question is being asked, I will often respond first by explaining precisely what Reformed theology is not. This method of identification, traditionally called the “way of negation” (via negativa), usually employed in the identification of divine attributes, is a helpful way of approaching many subjects. Though it is not necessary to approach any subject according to this method, it can be helpful in our pursuit in understanding the complexities of particular subjects, especially when those subjects have been so poorly explained and so poorly understood. Reformed theology has long been a victim of such poor explanation and poor understanding.

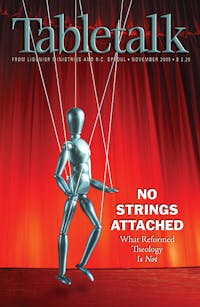

For nearly two years I fought against Reformed theology as it had been explained to me. When I was first introduced to the word “Reformed,” I was a freshman in Bible college, and, as a matter of fact, I was told that Reformed theology taught that man is basically a puppet on a string who has no freedom but is subject to a partial deity who whimsically picks those he wants to save and those he wants to toss into the eternal fires of hell. I was told about the “frozen chosen” who don’t believe it is necessary to evangelize or pray for the simple reason that it doesn’t matter what they do because God has predetermined all things.

My understanding of Reformed theology was completely skewed, and it wasn’t until I went to the Word of God and studied the sovereignty of God that I became convinced of Reformed theology. I discovered the biblical God, the biblical Christ, the biblical Gospel, and, consequently, the biblical doctrine of salvation. At a crossroads in my spiritual journey, I was humbled and amazed to find that Reformed theology is not a theology of determinism, that it is not opposed to prayer and evangelism, and that it is not the defender of a capricious deity who fools with the hearts of men as he would dance a little, faceless puppet on a string. Indeed, by God’s grace, and before His face (coram Deo), I was confronted with the beauty and simplicity of Reformed theology — a theology that is not anything other than the theology of Scripture.