Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

Looking across the landscape of evangelicalism, the most common misperception and criticism of Reformed theology is that it is incompatible with a high commitment to evangelism and missions. Even the slightest theological understanding and historical perspective should prevent such confusion, but the revivalistic bent of twentieth-century evangelicalism created a disastrous impression that retains cultural potency even today.

None of this would surprise Charles Haddon Spurgeon. Throughout his illustrious and culture-shaping ministry as pastor of London’s Metropolitan Tabernacle, Spurgeon faced the need to defend evangelical truth and to define evangelical Calvinism over against both misperceptions and misconstruals.

Spurgeon was always most powerful in his pulpit. On February 7, 1864, Spurgeon delivered a message on Exodus 33:19 entitled, “Election No Discouragement to Seeking Souls.” This message became something of a touchstone for Spurgeon’s ministry — representing a classic statement of his evangelical commitment to Reformed theology and of his passion for conversions.

In this sermon, Spurgeon responded to those who claimed that the doctrine of election betrayed a vision of a harsh and unloving God. “God is good, infinitely good in His nature,” Spurgeon insisted. “God is love; He willeth not the death of any, but had rather that all should come to repentance. …Our friends very properly insist upon it that God is good to all, and His tender mercies are over all His work; that God is merciful and gracious, slow to anger, and plenteous in mercy; let me assure them that we shall never quarrel on these points, for we also rejoice in the same facts.”

Spurgeon refused to see or to acknowledge a conflict between God’s omnipotent will and His love. “There is not the slightest shadow of a conflict between God’s sovereignty and God’s goodness. He may be sovereign, and yet it may be absolutely certain that He will always act in the way of goodness and love. … If the sons of sorrow fetch any comfort from the goodness of God, the doctrine of election will never stand in their way.”

The doctrine of election should not cause troubled souls to doubt the goodness of God, Spurgeon insisted, but to doubt their own confidence apart from the work of Christ.

“Let such remember that God is just as well as good, and that He will by no means spare the guilty, except through the great atonement of His Son, Jesus Christ. The doctrine of election … does come in, and breaks the neck, once for all, of all this false and groundless confidence in the unconvenanted mercy of God.”

The doctrine of election simultaneously affirms the glory of God and the helplessness of sinners, Spurgeon explained. Human pride falls dead at the foot of the cross, he believed, and nothing made this so clear as the Reformed doctrine of election.

Spurgeon’s ministry was intensely evangelistic, with the proclamation of the Gospel at the very center of his preaching and with thousands of faithful church members distributed throughout the world as evangelists, missionaries, and witnesses. As Iain H. Murray argues, “It was Spurgeon’s own persuasion of the love of Christ for the souls of men that lies at the heart of his weekly evangelistic preaching in London for thirty-seven years.”

Spurgeon was a deeply honest man, and he also confronted those who considered themselves to be committed to Reformed theology, but were opposed to evangelism. He preached faith as a duty, and called for persons to believe in Christ. Without apology, he stared down those, who by their denial of God’s saving purpose, brought Reformed theology into disrepute.

The charge of diminished evangelistic passion and missionary commitment emerged over the last two hundred years as evangelical theology was itself in foment. Spurgeon simply pointed to the legacy of the modern missionary movement, driven by men such as Andrew Fuller and William Carey, whose missionary vision was deeply grounded in Reformed theology.

In our day, John Piper has helped a new generation to understand how Reformed convictions produce a profoundly compelling missionary vision. The doctrine of election points to the glory of God, and the glory of God is demonstrated in the gladness of peoples who have come to know Christ as savior.

As Piper explains, “A heart for the glory of God and a heart of mercy for the nations make a Christ-like missionary. These must be kept together. If we have no zeal for the glory of God, our mercy becomes superficial, man-centered human improvement with no eternal significance. And if our zeal for the glory of God is not a reveling in His mercy, then our so-called zeal, in spite of all its protests, is out of touch with God and hypocritical.”

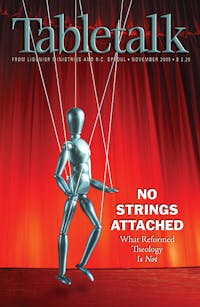

Remember these witnesses the next time you hear that Reformed theology leads to a lessening of evangelistic commitment. Those who know that God saves and the purpose for which He saves, should be the most eager and faithful witnesses to see others come to faith in the Lord Jesus Christ. Uncommitted to evangelism? That is what Reformed theology is not.