Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

The founders of the first Presbyterian seminary in America wanted it to be synonymous with Reformed theology. They intended Princeton Seminary to produce pastors and scholars sound in doctrine, fervent in piety, and committed to defending traditional Calvinism.

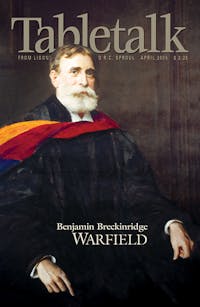

Benjamin B. Warfield, like his predecessors at old Princeton, reveled in the delights of Reformed theology. Eschewing theological innovation, Warfield continued the heritage bequeathed to him by Archibald Alexander, Charles Hodge, and A. A. Hodge of making a plethora of contributions across the theological disciplines. But his most enduring legacy lay in apologetics and specifically in defense of the authority, inspiration, and inerrancy of the Bible.

That Warfield should propel orthodoxy into the twentieth century was no accident. He merely continued the traditions established in the “Plan of a Theological Seminary” (1810), which spelled out the organization, curriculum, and piety that defined Presbyterians’ educational mission. All elements of the curriculum would contribute to its distinctive biblical perspective. Students were to master the Bible in the original languages so that they could critically analyze and illustrate the biblical text. In addition they would graduate as competent defenders of the faith fully conversant with the Westminster Confession and Catechisms. And, of course, they would demonstrate a firm acquaintance with the history of the Christian church.

Christianity offered a faith worth defending not only among scholars but wherever thoughtful questions arise. At its founding, the Princetonians focused their apologetic against the remnants of eighteenth-century deism. But when Warfield assumed the chair in systematic theology in 1887, liberalism had superseded deism. Radical biblical critics took aim at the conservative view of the Bible. Warfield’s prolific pen produced no less than forty-one articles, reviews, pamphlets, and essays espousing an evangelical view of Scripture. An entire volume in the Oxford collection of his writings is entitled Revelation and Inspiration. The sheer volume of his literary output testifies to the enormous pressure conservatives felt from liberals to water down orthodoxy among mainstream denominations between the Civil War and the 1920s.

Warfield’s apologetic for the Bible assumed two forms. First, he demonstrated that liberalism rested on a hypothetical construct, a series of assumptions devoid of argumentative value because it lacked any genuine connection with Christianity’s origin in the Bible. Without clear affirmation of the faith’s founding documents as divine, liberalism lost credibility in its claim to be Christian. He painstakingly reviewed world-renowned liberal scholars demonstrating that their recasting of Christian doctrines rested not on biblical evidence but upon an alien, naturalistic worldview foisted upon those very documents that radically altered their contents.

Liberals compounded their error by redefining revelation and questioning the Bible’s authority and reliability. Therefore, Warfield mounted his second argument — a full-throttled defense of the Scriptures. He did so on two intellectual planes: at the highest academic level in scholarly journals and in periodicals serving Presbyterian laypersons in the pew.

Warfield set his sights on achieving three goals. First, he identified exactly what Scripture claimed for itself. While citing the Bible’s self-referential claims did not prove them correct, it established exactly what was at stake in liberals’ assault of the Bible and of the utmost necessity of defending traditional views of Scripture. Warfield’s easiest task was to show that the biblical writers claimed inspiration from God — that the words of Scripture were literally “God-breathed.” Citing a host of Old and New Testament texts, he analyzed the use of “inspire” to demonstrate that God’s “breathing out” results in a divine, authoritative product (for example, Psa. 33:6; 2 Tim. 3:16–17; 2 Peter 1:19–21). Equally important, Warfield claimed that the church’s acceptance of the Bible as inspired and trustworthy in all that it claimed merely imitated our Lord’s use of the Old Testament in His earthly ministry. Jesus repeatedly cited Jewish scripture to settle a debate or make an authoritative point by asserting “it is written” followed by an Old Testament citation. Warfield also showed the equivalence of “Scripture says” with “God says” in numerous texts, and he stated that Jesus uttered His highest estimation of the Old Testament when He affirmed of a controversial text (Psa. 82:6): “the Scripture cannot be broken” (John 10:34, 35).

Secondly, Warfield delineated the issues separating liberal and conservative views of the Bible. Whereas liberals redefined the inspiration and authority of the Bible by focusing almost exclusively on the human factor in its writing, Warfield tenaciously defended Scripture’s divine origin along with its human authorship. He admitted that some scholastics so emphasized the divine element that they were not content to identify the writers as amanuenses (“penmen”), but surpassed sound judgment by representing the authors as “pens,” mere passive implements of the Holy Spirit. Their theories of inspiration tended toward a mechanical view in which God dictated the contents, virtually bypassing any human input.

Theological liberals, however, veered to the opposite extreme of scholastics by excluding divine authorship altogether. Radical critics flooded the marketplace of ideas with treatise after treatise affirming the Bible as merely a human book in origin and character. In this view, the Bible emerges as merely the record of human religious experience. Warfield cited scholars who parroted Enlightenment ideas, one-sided views that if the Bible is a human product, it cannot at the same time be divine in origin.

In contrast, Warfield insisted that the Bible affirmed both divine and human authorship. On the human side, various books displayed the character or personality of their authors. Biblical texts bore traits of human authorship by differing substantially in vocabulary and style. He went so far as to say that no responsible conservative scholar denied the humanity of the Bible by affirming a dictation theory of inspiration.

Warfield’s solution to this supposed impasse affirmed what he called a concursus based on the Bible’s consistently representing a coherence of God’s providence and human acts. God transcends His creation yet works immanently at every point in time and space in such a way that both His divine activity and human activity are fully supported. Our salvation, for example, is wholly the work of God yet we also “work out our salvation with fear and trembling.”

Analogously, the Bible unambiguously attributes authorship to God and the human writers. Thus the entire Bible, not just parts, was the product of God’s divine activity yet in such a way as to diminish neither the mind-set, vocabulary, and individual gifts of the human writers nor the characteristics associated with divinity. Each works together harmoniously with the other without diminishing the role of the other. Warfield summarizes: “The whole Bible is recognized as human, the free product of human effort in every part and word. And at the same time, the whole Bible is recognized as divine, the Word of God, his utterances, of which he is in the truest sense the Author.”

Although Warfield utilized the technical term concursus, he defended the Bible using language that inspired confidence that its content being divine carried the highest authority. Without explicitly mentioning propositional revelation, he provided a rationale for accepting the veracity of the Bible’s teaching a

s the revelation of God through the vehicle of human language.

Finally, Warfield gave precision to the church’s view of the full trustworthiness of the Bible by affirming its inerrancy. His opponents frequently misrepresented this teaching in the late nineteenth century and again in the 1970s when the struggle to define the evangelical view of the Bible resurfaced. In both instances, critics declared inerrancy a contemporary innovation in church history, a last-ditch tightening of terms to meet the onslaught of biblical criticism. They particularly charged the term a “diversion” from the Westminster Confession mentioned in the Plan of the Seminary.

Warfield responded in two ways. He argued that although Westminster did not use the word inerrancy, it is implicit in Westminster’s affirmation of the Bible’s divine inspiration and its infallibility. If Scripture originated from God, it must inherently bear such qualities as perfection, perspicuity, and trustworthiness consistent with God as its author. While Warfield granted that discrepancies crept into translations, we must affirm inerrancy of the autographs (the original documents).

He admitted that “inerrant in the original autographs” is an awkward construction. But he deemed that a small price to pay for opposing those who claim faith in the Bible yet contend it errs when it speaks historically. The liberal position does nothing less than undermine the Bible’s authority as the revelation of God’s redemptive activity.

Moreover, Warfield substantiated beyond doubt that the term inerrancy was no latecomer to church history as critics alleged. He cited examples from early church fathers such as Augustine to Reformers Martin Luther and John Calvin to Puritans like Richard Baxter. They either used the term inerrant as characterizing the Bible or stated that while corruptions existed in extant manuscripts, the autographs contained no such problems. Far from this distinction being unknown among the Westminster divines, Warfield characterized it in “The Inerrancy of the Original Autographs” as “the burning question” of the day among Puritan divines.

Warfield’s defense of the Bible’s inspiration, authority, and inerrancy remain among the most lucid and persuasive in the modern era. They testify to the wisdom of the founders of Princeton Seminary and continue to influence those who defend the Bible from a Reformed perspective.