Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

There’s no accounting for taste. Or to put it another way, the taste has reasons that reason knows not of. We like what we like, and we don’t like having to explain it. Which is why postmodernism fits us so well. Here it’s not just flavors of ice cream, but all of goodness, truth, and beauty that gets reduced to a matter of taste. And no one has to defend their tastes, for we can all be right. What makes less sense, however, is why, if there are indeed no standards, our tastes tend to follow patterns. If taste is simply random, then it seems there ought to be as many folks who prefer the sound of fingernails on chalkboards (sorry for those of you who get the sensation at the mere mention of the act) as there are folks who prefer Pachelbel’s “Canon in D.” Ask any record store manager — it just isn’t so. One would think that the Uniform Commercial Code would sell as many copies as Tolkien. But it doesn’t happen.

We aren’t the products of chance, else our choice in products would come out like chance. Instead we are what we are, and what we are is rebels. That we prefer Pachelbel to fingernails is a reflection of our Maker, evidence that we are, even in our rebellion, made in His image. That we don’t much care for the Pentateuch shows that though we bear His image, we are in rebellion against Him.

In recent years all the world has gone gaga over The Lord of the Rings, especially the movie adaptation. Though as I write it is still September, my eight-year-old son already has visions of extended versions dancing in his head. He has read and loved The Hobbit for much the same reason. Tolkien has given us another land, a land filled both with bucolic villages and epic battles, with fidelity and treachery, maidens and a mysterious hero who is heir to the throne. It stirs the hearts not only of children, but of men.

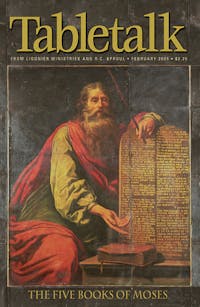

Which is why it is so puzzling that we, both within and without the church, are more enamored with the four books of Tolkien than the five books of Moses. What does Tolkien have that Moses has not? Here we find not a bucolic village, but better still, an edenic garden. Here we find betrayal on an immeasurable scale, and fidelity to the infinite degree. Here we have wicked tyrants who are brought down low, slavery and freedom, miracles and talking beasts and bushes, dragons and damsels, and in the shadows, the promise of an heir.

The difference in our taste then isn’t in what Moses left out and Tolkien put in. Instead it is found in what Moses put in, and Tolkien left out. We turn up our noses at the Pentateuch not because of the adventure therein, but the Law. It isn’t the parts that read like titanic battles, but the parts that read like the Uniform Commercial Code. The problem with the Pentateuch to our postmodern ears isn’t the story, but the Law. Tolkien, to be sure, gave us characters who were driven by law, enemies that acted lawlessly. But for all his attention to detail in creating his “alternate universe,” for all the language, music and arcana, there is no law.

Moses, on the other hand, not only gives us the great commandment, but he opens it up for us, twice, giving us the Ten Commandments both in Exodus and Deuteronomy. But just as the ten stones fill out the meaning of the great commandment, so does the rest of the Law fill out the ten. We are told by Moses exactly how many sheep must be returned for one stolen sheep, for proper restitution, and how many goats must be returned in like manner when a goat is stolen. We are told what to do with a bull that gores a man, and what to do with a bull that has simply wandered off the farm. We are given instructions on how to sacrifice a bull, and how to build the grate on which he will burn. And no one could be interested in that.

Except David, a man after God’s own heart. “Oh how I love your law” David cries, “It is my meditation all the day” (Psalm 119:97.) Psalm 119 in fact is the longest chapter in all the Bible, and is nothing more than an extended poem praising the law of God.

There is not only a connection between this psalm and the Pentateuch, but a connection between our love of story, and David’s love of Law. The glory of the story isn’t found in the high drama, but in the high Dramatist. The glory of the story is the glory of the Father. The great purpose of the Pentateuch is that we would more clearly behold the glory of God. What we have missed is that the same is true of His law. Yes the Law shows us our need for Christ. Yes it restrains the heathen. And yes it shows us how to please our Father. But we long to please our Father because of His glory, and the Law shows us that glory. It is lovely for precisely the same reason that Pachelbel’s “Canon” is lovely, because it shows forth the glory of God.

Such is the purpose of all that is true, all that is good, and all that is beautiful. It all exists to show us God. May we by His grace, and for His glory, learn to see His grace in revealing His glory, in giving us His law.