Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

They were heralded as the architects of a “new orthodoxy.” Their distinguished group included such scholars as Karl Barth, Emil Bruner, Paul Althaus, and, in the early years, Rudolf Bultmann. Barth was the acclaimed leader of this movement, called variously “dialectical theology” or “neo-orthodoxy.”

Like Barth, most of them were educated in the canons of nineteenth-century liberalism, being molded by the thinking of G.W.F. Hegel, Albrecht Ritschl, Friedrich Schleiermacher, and others. They also were influenced by the existential philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard.

And yet, in many ways, the rise of neo-orthodoxy was a sharp reaction against liberalism. Barth once spent a semester lecturing on the theology of Schleiermacher. During his lectures, he had on his desk a bust of Schleiermacher, to which he would address questions and criticisms. On the last day of the class, he finished his lecture, then walked over to the bust and knocked it to the floor, where it shattered into pieces. Barth wiped his hands, grinned, and said, “So much for Schleiermacher.”

Barth and his allies were concerned about the strong tendency toward pantheism found in Hegelian and idealistic philosophy. They saw that the emphasis on the immanence of God so identified Him with the universe that His transcendence was obscured. If history is seen as the unfolding of the Absolute Spirit, then God Himself is trapped within and shaped by the world.

Barth believed this thinking was a result of the invasion of speculative philosophy into the realm of Biblical revelation, an intrusion of an alien rationalism that turned God into Reason with a capital R. He wanted a return to a Biblical theology that was not controlled by logic or other Aristotelian concepts.

However, Barth’s rejection of liberalism did not mean that he simply reaffirmed classic Christian orthodoxy. Indeed, he was sharply critical of orthodoxy, denying the inerrancy of Scripture and with it both general revelation and natural theology. The thought of Thomas Aquinas came in for special criticism. For instance, Barth attacked the Thomist notion of the analogy of being (analogia entis), seeing in it the illegitimate use of an abstract concept of being that could apply both to God and to man.

To overcome the emphasis on the immanence of God in liberalism and to reassert the transcendence of God, the neo-orthodox theologians employed a phrase that has since crept into the vocabulary even of otherwise orthodox scholars. It is the term wholly other. They said God is not analogous to us but is quite different from us. He is other—not in part but in whole. He is totally different from us.

Thus, in their zeal to rescue God from immanentism, the neo-orthodox theologians fell into the error of the opposite extreme. The term wholly other is not only erroneous, it is exceedingly dangerous. Indeed, it doeserase the analogy of being, but it also wipes out any possibility of the knowledge of God.

Why is that? To answer this question, I will illustrate by recalling a dialogue I had with a group of theological scholars who were critical of my approach to apologetics because it relied on logic, reason, and natural theology. They argued that God cannot be known from nature because God is wholly other from nature.

I replied by asking them how God can be known. Without hesitation they answered, “By revelation.” I pushed the issue by asking, “But how can God reveal Himself?” They responded, “Through His Word [the Bible], through Christ, and through redemptive history.”

By now it was clear to me that they were missing the force of my questions. So I put it plainly and directly. I said: “If God is ‘wholly other’ in the sense in which you are using the concept, if He is utterly and totally dissimilar to us, how could He possibly communicate anything meaningful about Himself to us? There would be no possible point of contact with our understanding between Him and us.”

Suddenly the lights went on as they realized that if God were really wholly other, the only way we could speak of Him would be via the way of negation, by saying what He is not. This leaves us with Greek thought (Neoplatonism) with a vengeance. They responded in a manner like to that of a man who smacks himself in the forehead. “Perhaps we shouldn’t say God is wholly other,” they said.

Precisely. This concept should never be used by orthodox Christianity. It leaves us groping in darkness with only flimsy and unsound appeals to revelation, which revelation is not even possible.

It is because there is some analogy or similarity between us and God that revelation takes place. We really are created in God’s image. That fact makes communication between God and us possible.

As a young college student, I attended a series of lectures at Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia. It was in the halcyon days of that institution, when its faculty boasted such luminaries as Ned Stonehouse, E.J. Young, John Murray, and especially Cornelius Van Til. Van Til was a sharp critic of Barth, so sharp that Barth referred to him as a “man-eater.”

During the conference, I was seated at the lunch table across from the professor of philosophy. I had just tasted some soup when the professor looked at me and said, “Young man, is God transcendent or immanent?” With an involuntary spasm, I spat the soup out of my mouth and nearly choked to death. I had no idea what the terms transcendent and immanent meant.

Seeing my embarrassment, the professor rushed to my aid. He explained that God is both transcendent and immanent. He is higher than the cosmos. He rises above and beyond it. His greatness surpasses anything that is creaturely. Yet at the same time, He is “connected to” His creation. He is immanent in His infinite being; He is immanent in history with His redemptive works, especially in the person of the incarnate Christ; He is immanent in His providential government; and He is immanent in our lives in the presence and power of the Holy Spirit. God is both above us and with us. To make Him totally identified with creation is to obscure His transcendence and slip into pantheism. But if we make Him totally transcendent, we slip into deism or sheer skepticism.

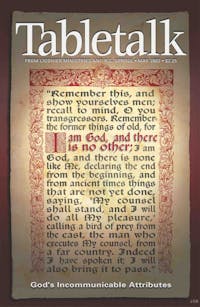

God reveals Himself in creation, but He is not the creation. The heavens declare His glory, but He is not the heavens. We are created in His image, but we are not gods. He is not to be identified with anything creaturely, but neither is He so remote as to be “wholly other.” Rather, He is holy other. He is transcendent in His majesty, power, and being.