Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

It is one of the cruelest ironies of American history that Cotton Mather (1663–1728) is generally pictured unsympathetically as the archetype of a narrow, intolerant, severe Puritanism, who proved his mettle by prosecuting the Salem witch-trial debacle of 1692. In fact, he never even attended the trials—he lived in distant Boston—and actually denounced them. And as for his Puritanism, it was of the most enlightened sort.

Indeed, Mather was a man of vast learning. He owned the largest personal library in the New World—four thousand volumes ranging across the spectrum of classical learning. He was also the most prolific writer of his day, producing some 450 books on religion, science, history, philosophy, and poetry. He was the pastor of the most prominent church in New England—Boston’s North Church. He was active in civic affairs, serving as an advisor to governors, princes, and kings. He taught at Harvard and was instrumental in the establishment of Yale. He was the first native-born American to become a member of the scientific elite in the Royal Society. And he was a pioneer in the universal distribution of the smallpox vaccine.

His father, Increase Mather, was the president of Harvard, a gifted writer, a noted pastor, and an influential force in the establishment and maintenance of the second Massachusetts Charter. In his day, he was thought to be the most powerful man in New England—in fact, he was chosen to represent the Colonies before the throne of Charles II in London. But his obvious talents and influence actually pale in comparison to those of his son.

Likewise, both of Cotton Mather’s grandfathers were powerful and respected men. His paternal grandfather, Richard Mather, helped draw up the Cambridge Platform, which provided a constitutional base for die Congregational churches of New England. His maternal grandfather, John Cotton, wrote the important Puritan catechism for children, Milk for Babes, and drew up the Charter Template with John Winthrop as a practical guide for the governance of the new Massachusetts Colony.

According to historian George Harper, together these men laid the foundations for a lasting “spiritual dynasty” in America. Even so, according to his lifelong admirer, Benjamin Franklin: “Cotton Mather clearly out-shone them all. Though he was spun from a bright constellation, his light was brighter still.” And according to George Washington, “He was undoubtedly the Spiritual Father of America’s Founding Fathers.”

Mather was assuredly a man of splendid talents and varied interests whose impact covered the whole field of human endeavor, but his greatest contribution may well have been pioneering a theology of Biblical piety and practice. According to Harper: “His supreme achievement lay in drawing on the perspectives of English Puritans like Richard Baxter and German Pietists like August Hermann Francke to forge a distinctive American theology. This new piety would finally come into its own with the flowering of evangelicalism in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Mather’s ministry bridged the gap between what was and what was to be.”

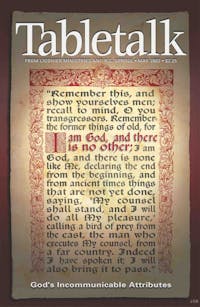

Mather was able to combine deep devotion and strident action into a single and cohesive vision for life and ministry that gave a unique tenor to the nascent American mind-set. For Mather, this peculiar combination of virtues was supremely Scriptural—drawn from the very character of God. “Cognizant of His sovereignty, alert to His providence, and respectful of His majesty,” Mather believed there was no alternative but to “yield to every dimension of true discipleship,” regardless of the “adjustments of life and comfort” such yielding “might effectuate.” It was simply a matter “demanded by the very attributes of the Lord.” His life and faith were vitally invigorated by an apprehension of that which cannot be fully apprehended, by an estimation of that which cannot be fully estimated, and by a comprehension of that which cannot be fully comprehended: God’s own incommunicable nature.

Mather’s sober expression of God’s attributes anticipated that of the Westminster divines by a generation—that the “immutable, immense, eternal, incomprehensible, almighty” God has “all life, glory, goodness, blessedness, in and of Himself; and is alone in and unto Himself all-sufficient, not standing in need of any creatures which He hath made, nor deriving any glory from them, but only manifesting His glory in, by, unto, and upon them,” and is therefore due “from angels and men, and every other creature, whatsoever worship, service, or obedience He is pleased to require of them.”

Cotton Mather was a man who knew God, disciplined the protocol of his life accordingly, and thereby was used in the good providence of God to alter the destiny of this nation forever.