Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

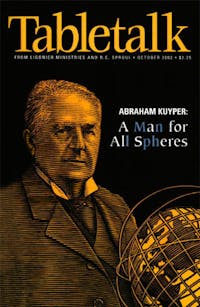

If we had monitored political discussions among American evangelicals during the past generation, the authority we would have heard quoted most often probably would have been a Dutch pastor, Abraham Kuyper (1837–1920). For whatever reasons, recent American evangelicalism has not produced a figure whose insight and influence supercedes Kuyper’s. Thus, he endures as the handiest political icon for evangelical imitation.

In truth, Kuyper has become the virtual patron saint of modern evangelicalism’s revived interest in politics. Leaders ranging from Francis Schaeffer to C. Everett Koop to John Whitehead or Jack Kemp to James Dobson or Ralph Reed occasionally acknowledge his tutelage.

Interests

Raised in a pious home as the winds of modernism blew through Holland, Kuyper pursued a career in pastoral ministry, even though unconverted. After a thoroughly modern education, he was converted while in the parish ministry. That conversion left a lasting distaste for the fleeting fads of modernity—which he styled a “fairy-like Morgana”—both in his soul and his politics.

One of the key influences in Kuyper’s conversion was Dutch historian William Groen Van Prinsterer (1801–1876). Kuyper was greatly influenced by Groen’s 1847 Lectures on “Unbelief and Revolution,” which critiqued the Enlightenment and the French Revolution with Calvinistic convictions in Burkean proportions.

For Groen, the French Revolution of 1789 was singularly symbolic, signifying far more than an isolated coup. It represented an entire vein of philosophic thought that was man-centered and opposed to God’s sovereignty. These revolutionary ideas became the philosophic program for Western humanism expressed politically.

Groen and Kuyper agreed that the Reformation’s principles stemmed the swelling tide of humanistic unbelief. This germ of unbelieving thought—or “political atheism”—had been arrested only by the steady advance of Reformation thinking. In terms reminiscent of Groen, Kuyper saw the major political options in his own day as a choice between the “Liberty Tree” or the “Cross,” protesting, “Christ, not Voltaire, is the Lord Messiah over the nations.”

Kuyper would devote the remainder of his political and ministerial life to the restoration of those sturdy Calvinistic political impulses that had once been characteristic of Dutch politics. His rationale, derived from Groen, was rather consistent: There were two major worldviews—Enlightenment revolutionism or Reformation Calvinism. The latter led to liberty, stability, commerce, and education, while the former engendered oppression, anarchy, socialism, and regression. For Kuyper, the Reformation worldview was the natural overflow of “mere Christianity.”

The principles of Kuyper’s political formulations, he thought, were both Biblically sound and logically implied. Kuyper articulated those principles in sermons, lectures, political speeches, daily editorials, and party platforms for decades before most Americans would hear about his work.

Principles

When Kuyper delivered the Stone Lectures at Princeton Seminary during a U.S. speaking tour in 1898, he argued that political authorities cannot claim absolute loyalty, the state is not omni-competent, and humans never possess power over others, except as God permits. Limited government and limited exercise of power are hallmarks of Kuyperian thought. While arguing for small-government republicanism, the future prime minister of Holland also asserted, “No political scheme has ever become dominant which was not founded in a specific religious or anti-religious conception.”

At the heart of this thought was a simple notion: Politics are not neutral but always are wedded to ultimate issues. Thus, political ideas should be judged by their religious roots as well as their practical effects. For Kuyper, two main trunks contributed to modern politics: a humanistic strain stemming from the French Revolution and a religious branch arcing back to the time of Calvin’s Reformation. One of those two ultimate roots would dominate politics, and the fruit would be discernible.

Kuyper argued that the old bugaboo, “sin,” affected both rulers and the ruled. “Hence,” he said, “resistance, insurrection, and mutinies will not end, unless a righteous constitution bridles the abuse of authority” and protects citizens against “despotism and ambitious schemes.” That greatly spurned theology of sin still rests at constitutionalism’s base.

Kuyper believed that his faith required certain political elements. He was convinced that the reality of sin necessitated government, but government of limited activity, so he advocated constitutionalism and smaller government. He also called for each non-political sphere to perform its own tasks without becoming dependent on politicians.

Accordingly, Kuyper’s concept of “Sphere Sovereignty” erected a levee against statist encroachment into spheres where the state had no proper jurisdiction. Sphere Sovereignty confesses the limitation of political power, an aspect of political formulation that is sorely needed today. Kuyper affirmed that God decreed divided power and never ceded all His power to a single institution; instead, He delegated power and authority to each sphere to execute its nature and calling. Part of the genius of Sphere Sovereignty is its preservation of the delicate balance between social institutions. As ordered by God, each social unit carries out its own charter, and other spheres are not to interfere with the duties of other units.

Kuyperian thought dignifies the family as a legitimate government sphere in microcosm. And Kuyper maintained that governing spheres should not usurp the domain of the family or that of any of the other social spheres. The state has no sovereignty to intrude into the private sector, the family, or the church. All the various social spheres are independent of the state—neither derived from it nor giving obeisance to it. Instead, they “obey a higher authority within their own bosom.” Thus, the state cannot properly impose its will over private sectors: “The State may never become an octopus, which stifles the whole of life. It must occupy its own place, on its own root, among all the other trees of the forest, and thus it has to honor and maintain every form of life which grows independently in its own sacred autonomy.”

Simply put, Kuyper’s Calvinism derived essential liberties from the sovereignty of God and erected a “dam across the absolutistic stream” of man-centered political force.

A Kuyper for Dummies volume might summarize the five points of Kuyper’s political thought as:

1. Constitutionalism (to limit subjectivity and depravity);

2. Republicanism (to balance authority and freedom);

3. Sphere Sovereignty (to support robust microcosmic levels of government and to protect from authoritarianism);

4. Integration or non-separation of faith from politics (to minimize secularism and an Enlightenment bias);

5. Realistic anthropology (to minimize utopianism and socialism).

Nevertheless, these principles, however strong, would not take root apart from consistent promulgation and a strong practice.

Practice

The heart of the Kuyperian political project is practical as well as theoretical. Kuyper devoted thousands of hours to speaking, popular writing, and party organization. His passion for the principles listed above led him to seize every workable medium to promote these organic ideas. He even tailored much of this thought to the masses, and recent studies illuminate how his poetic style and rhetoric furthered his principles’ longevity.

Others eventually recognized his genius. Lutheran theologian Helmut Thielicke summarized: “Kuyper finds the religious and Reformed character of the American Revolution confirmed in a statement of Alexander Hamilton: ‘The French Revolution is no more akin to the American Revolution than the faithless wife in a French novel is like the Puritan matron in New England.’” Kuyper himself thought that, “The fanatic for Calvinism was a fanatic for liberty.”

One of Kuyper’s most famous aphorisms exhibits his thoroughly Christ-centered ethos. Most Christians say a joyous “amen” to his claim that “there is not a square inch of the universe over which King Jesus does not claim, ‘Mine!’”

In contrast to the utopianism of state-centered schemes, Kuyperians know that if we live in a fallen universe, then politics must be pursued accordingly. We may appreciate one of Kuyper’s exhortations: “As for us and our children, we will no longer kneel before the idol of the French Revolution; for the God of our fathers will again be our God.” That’s about as revolutionary as Colonial Calvinism!