Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

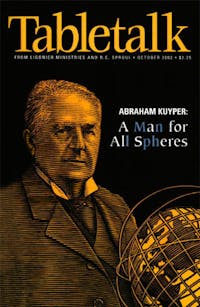

In the early 1970s, I was browsing through dusty volumes in a used-book store in downtown (pronounced dahn-tahn) Pittsburgh. To my astonishment and delight, I found a copy of a book of sermons written by Abraham Kuyper. Because the volume was in Dutch, few customers had showed any interest in it. Therefore, by the immutable law of supply and demand, the asking price was 25 cents. For one quarter I was able to secure a book that in other parts of the world would be regarded as a treasure. One man’s garbage. . .

I first heard of Kuyper while I was a philosophy student in college. My main professor had been deeply influenced by Kuyper and by Kuyper’s students. At that time, I had no idea how great an influence this man would have on my own life.

In 1964, I graduated from seminary. I had been married for four years, and we had a 3-year-old daughter. I was tired of going to school and more than ready to get a full-time job. But my theology professor had other plans. Only a few weeks before graduation, my mentor sat me down and insisted that I go on to graduate school. I said, “If I go, where should I go?” Without hesitation he replied, “To the Free University of Amsterdam.” He wanted me to study under G.C. Berkouwer, and since Berkouwer held the chair of theology at the Free University, that’s where I had to go.

At the time, I was not aware that “The Fu” (the students’ affectionate term for the school) had been founded by Kuyper. Kuyper, a theologian, philosopher, and politician in the Dutch Calvinist tradition, founded the university in 1880. He served there as a professor and administrator. He also served his country as a member of Parliament for more than 30 years and was the prime minister of the Netherlands from 1901 to 1905. At his 70th birthday party in 1907, it was said of him that “The history of the Netherlands in church, in state, in society, in press, in school, and in the sciences of the last forty years, cannot be written without the mention of his name on almost every page.”

At first glance, it may seem that Kuyper the educator structured the Free University according to the classical pattern of the medieval university, where theology was regarded as the queen of the sciences and philosophy as her handmaiden. At the Fu, theology and philosophy held center stage. The second glance, however, reveals that Kuyper did not seek to replicate the medieval model because he saw it as too dependent on the role of human reason and natural theology.

The Free University was so called not because there were no tuition costs. The “free” had to do with its status with respect to both church and state. The university was free in the sense that it was independent, bound only by the Word of God. Kuyper had a profound influence on the thought of Herman Dooyeweerd, who was both a student and later a professor of philosophy at the Free University. Dooyeweerd, like his mentor, was deeply concerned about “worldview” thinking and with the “cultural mandate,” the task given to Adam and Eve to subdue the earth. For Kuyper and his students, all thought must be brought into subjection to the sovereignty of God. All culture, all science, and all knowledge must be understood in light of God. Fields of inquiry may be distinguished from theology, but never separated from it. Kuyper had no place for a truncated worldview in which theology was relegated to a tiny compartment of spirituality. All of culture was to be under God’s sovereignty.

Dooyeweerd, in his massive (and somewhat arcane) four-volume work, A New Critique of Theoretical Thought, and in other works, leveled a sharp criticism against the secular foundations of Western thought. He argued that secular worldviews are blind to their own “religious” commitments. Secular thinkers are caught in a pretense of their own sense of autonomy. Every thinker has his own “cosmonomic” idea. This idea of cosmic law describes the general structure, grid, or framework into which the scholar or scientist fits and interprets the particular “facts” of his knowledge.

There is a line that runs from Kuyper to Dooyeweerd to Cornelius Van Til and to Francis Schaeffer. Though each of these thinkers had his own unique contributions, there is a common connection among them in the call to bring all knowledge into subjection to God.

For Kuyper and his followers, there was no such thing as “neutral” knowledge or education. One’s knowledge is related to God or it ignores Him. For Dooyeweerd, the “heart” refers to the functional center or core of a person’s being. Reflecting the Biblical axiom that “As a man thinks in his heart, so is he,” Dooyeweerd said the heart of man is either inclined toward God and submissive to Him or is set against Him.

The Free University was Kuyper’s legacy to worldview thinking. When I enrolled in the Theological School in 1964, it was located in the inner city of Amsterdam, just around the corner from the Anne Frank house. Today the university has expanded and moved to the suburbs, not far from the international airport of Schiphol. It now comprises 15 faculties; two thousand lecturers and researchers, including three hundred professors; sixteen hundred non-academic staff members; and facilities for fourteen thousand students. It includes a major teaching hospital as part of its program. This great university lives on as one of Kuyper’s many legacies.