Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

After church one Sunday morning, one of my parishioners, who comes from my hometown of Pittsburgh, asked me whether I thought our favorite sports team would win its upcoming game. I replied, “I sure hope so.”

My answer was not a prediction of the outcome; it was simply an expression of my desire as to the outcome. It described my wish for the future, not my foreknowledge of the event. Indeed, it revealed both my lack of foreknowledge and my lack of assurance.

The combination of a wish (or desire) and the absence of assurance that it will come about is the equation for the common meaning of the word hope in our vocabulary. Because of this customary usage of the term, we often stumble when we meet the word hope in Scripture. In New Testament terms, hope transcends the flimsy element of wish projection. It is something far greater and far stronger than mere desire. In fact, the Bible elevates it to a place among the great triad of virtues that defines the Christian life—faith, hope, and love. These are the three that abide after all the clutter is cleared away.

In short, the New Testament concept of hope is bathed with assurance and cloaked with certainty. This hope is faith looking into the future.

Though hope and faith are distinguished, they are not disconnected or divorced from each other. There is a certain symbiotic relationship between them. We see this in the way the author of Hebrews defines faith as “the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen” (Heb. 11:1).

Here the word faith is defined in a manner that collides with the frivolous way it is used in our day. Notice that Hebrews speaks of faith in terms of substance and evidence. Faith without substance is superstition. Faith without evidence is credulity. Scriptural faith is not some blind, irrational leap into the dark. Rather, it both has substance and gives substance. This is solid faith, faith based upon the surety of the reliability of God. In faith we trust God not only for what He already has done for us, but for what He promises to do in the future.

I frequently say that it is one thing to believe in God, but it is quite another to believe God. When our faith moves beyond a mere intellectual assent to the existence of God to actually trusting His Word, then we experience faith.

Faith in things past carries over to trust in things future. Because God has proven Himself in the past, His promise for the future gives substance to our hope. The Las Vegas oddsmakers are wrong every week in their predictions about the outcomes of sports contests. Howie, Terry, et al. never have a perfect record for the season with their “expert picks.” But God doesn’t guess about future events. Neither does He offer expert prognostications. His promises carry the substance of who He is. In this sense, we experience hope as faith looking forward.

When Hebrews speaks of faith as the evidence of things unseen, it is making a similar point. The disciples’ faith in the resurrection of Christ was not a blind faith resting on the unseen. Christ appeared to them in visible form so they could declare to us what they saw with their eyes and heard with their ears. Faith is the evidence of things unseen in this way: New Testament faith is based on what is seen. The seen then bears witness to and gives credibility to what is unseen. The best evidence for trusting God in the future is His track record in the past. In this sense, faith gives evidence to hope so that the hope we have is not feeble but one that rests powerfully on the assurance of God Himself. It is described as the “anchor of the soul.”

Thus God, determining to show more abundantly to the heirs of promise the immutability of His counsel, confirmed it by an oath, that by two immutable things, in which it is impossible for God to lie, we might have strong consolation, who have fled for refuge to lay hold of the hope set before us. This hope we have as an anchor of the soul, both sure and steadfast, and which enters the Presence behind the veil, where the forerunner has entered for us, even Jesus. Hebrews 6:17–20a.

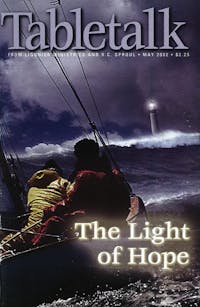

With such hope, our ship is not left anchorless to be tossed to and fro by fickle winds that buffet it. This hope is sure and steadfast. Furthermore, it gets us “behind the veil” and into the “Presence.”

In Paul’s letter to Titus, he speaks of the “blessed hope” of the church, the glorious appearing of our God and Savior Jesus Christ (Titus 2:13). The ultimate dimension of this blessed hope is the promised future experience of what is called the beatific vision, or the vision of God (visio Dei). We find this in 1 John:

Beloved, now we are children of God; and it has not yet been revealed what we shall be, but we know that when He is revealed, we shall be like Him, for we shall see Him as He is. And everyone who has this hope in Him purifies himself, just as He is pure. 1 John 3:2–3.

The vision of God is called the beatific vision because what is seen carries with it the greatest blessedness a human being can experience. We shall see Him as He is. At present, we have the secondary portrait of the Creator provided by His handiwork in creation. We “see” Him through His works. The people of God in the Old Testament had theophanies, visible manifestations of the invisible God, such as the pillar of cloud, the burning bush, etc. But even then, the face of God remained hidden from view; no one was permitted to see God. That we cannot see Him is not because of a deficiency in our optic powers. The deficiency is in our hearts. Sin is the shield that conceals His face from our eyes.

In the Beatitudes, Jesus promised that the pure in heart are the ones who will see God. Not until our hearts are purified from all sin will we gaze into the unveiled face of God. Then we will see Him as He is.

One glance at the unveiled glory of God will be enough to move the redeemed soul to spiritual ecstasy that will last forever. But the blessed hope promises more than a momentary glance. It promises an eternity of dwelling in the immediate presence of the unveiled glory of God. This is our hope, and it is a hope that cannot possibly leave us disappointed.