Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

We live in a time when preachers are told they must not really be preachers, but rather entertainers, facilitators, masters of ceremonies, or whatever the next hot-selling guru book for preachers will say they must be instead of preachers. This is all done in the name of making the Gospel relevant and palatable to the modern ear. And so long as this assumption continues unchallenged in the modern church, we will continue to have more of the same, which is to say, dated, temporal, irrelevant relevance.

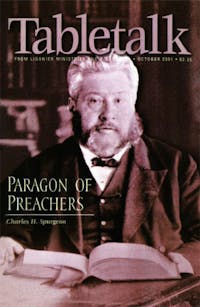

But Charles Spurgeon was a true preacher of eternal things. He understood his calling, as is seen clearly in his book Lectures to My Students. What he knew could be communicated to others.

One of the most striking things about his approach is his practical earthiness. Victorian preachers tended to be flowery, and Spurgeon himself was not entirely free of this tendency. But at the same time, what comes through in his book is a kind of practical shrewdness that rejoices the heart.

One illustration can be taken from one of his exhortations to ministerial cheerfulness. As he put it: “The Christian minister should also be very cheerful. I don’t believe in going about like certain monks whom I saw in Rome, who salute each other in sepulchral tones, and convey the pleasant information, ‘Brother, we must die,’ to which lively salutation each lively brother of the order replies, ‘Yes, brother, we must die.’ I was glad to be assured upon such good authority that all these lazy fellows are about to die; upon the whole, it is about the best thing they can do; but till that event occurs, they might use some more comfortable form of salutation.”

As Spurgeon taught preaching, he exhorted his students to reject the “perfumed prettinesses of effeminate gentility.” He had no use for foppery in the pulpit, and his rejection of it would seem insensitive to many. “Moreover, brethren, avoid the use of the nose as an organ of speech, for the best authorities are agreed that it is intended to smell with.”

His trust in God’s sovereignty did not distract him from a proper understanding of appointed means to ends. “The next best thing to the grace of God for a preacher is oxygen. Pray that the windows of heaven may be opened, but begin by opening the windows of your meeting-house.”

Spurgeon was also a master of the striking image. Not only did he urge his students to fall in love with words, to enjoy the rumble-bumble of them, he also set them a fine example in his lectures. “Don’t go about the world with your fist doubled up for fighting, carrying a theological revolver in the leg of your trousers. There is no sense in being a sort of doctrinal game-cock, to be carried about to show your spirit, or a terrier of orthodoxy, ready to tackle heterodox rats by the score.”

The striking images come from everyday life and by imaginative application from Scripture. “Molasses and other sugary matters are sickening to me. Jack-a-dandy in the pulpit makes me feel as Jehu did when he saw Jezebel’s decorated head and painted face, and cried in indignation, ‘Fling her down.’ ” In speaking of how little things can wreck a discourse as readily as a great problem, he noted that “pots of the most precious ointment are more often spoilt by dead flies than by dead camels.”

His was a sturdy Calvinism. It was not the truncated version of some doctrinaire brethren, but neither was it the broad and spacious moderate version. “Live on the substantial doctrines of grace, and you will outlive and outwork those who delight in the pastry and syllabubs of ‘modern thought.’ ” In short, he was a sunny Calvinist, with a direct and basic trust in a sovereign God.

This winsomeness was not at all inconsistent with his potent use of godly ridicule. “At another time, I may laugh the laugh of sarcasm against sin, and so evince a holy earnestness in the defense of the truth. I do not know why ridicule is to be given up to Satan as a weapon to be used against us, and not to be employed by us as a weapon against him.” When some objected that this was a dangerous thing to do, that men might cut their own fingers on the sharp edge of sharp language, he replied, “Well, that is their own look-out.” But even here, although his jabs were often laugh-out-loud funny, they were never vindictive or mean-spirited. This is difficult for us, because in the modern church we have come to the point where any disagreement at all can be considered a hate crime, and then, if the disagreement is coupled with any lively expressions of wit, we start considering the possibility of arranging compulsory counseling for the insensitive lout guilty of it.

This earthiness of Spurgeon’s (which abounds in his Lectures) was not a regrettable lapse in the life of an otherwise godly man. It was something we desperately need to regain.