Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

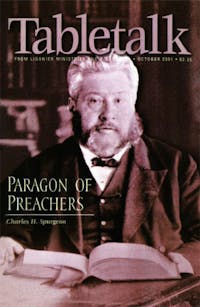

Charles Haddon Spurgeon was sui generi—one of a kind. Few others in church history combine his greatness as a preacher, a pastor, an evangelist, and a founder of a college. Not so well known, perhaps, but equally significant are his contributions to what might be called social reform—helping the poor and lifting the standard of public welfare in England.

He began preaching in London’s Metropolitan Tabernacle in 1853, when he was 19 years old. The small church soon exploded in growth and multiplied into new churches. Spurgeon’s evangelistic preaching led to conversions and discipleship, along with informal and then more formal pastoral training. A literature and book ministry grew rapidly, with the help of his wife, Susannah, and continues to provide a blessing to many people a century later. A college for training pastors was started, along with an orphanage and other programs to help the needy.

Yet the complete Spurgeon story begins at least two hundred years before his birth, when Christ began building His purposes and qualities into the ancestors who helped prepare the nineteenth-century pastor-teacher for his ministry. The principle of covenant succession—passing on the faith from generation to generation—is one of me major reasons he was able to accomplish what he did and why the ministry he founded continues to bear fruit even today. His family origins should encourage parents to not grow weary in well doing. We cannot know from which covenant family the next Spurgeon might emerge or which covenant families are preparing the kind of believers who joined with Spurgeon to make him successful in such an unusual period of reformation.

Job Spurgeon, a seventeenth-century ancestor of our subject, was sent to jail in England in 1677 for refusing, like John Bunyan, to stop preaching the Gospel. That kind of conviction for Christ appears to have been passed down through Spurgeon’s family. Charles Spurgeon’s grandfather, James Spurgeon, became a pastor of an independent church in the late 1700s. He had 10 children, the second-born of whom was John Spurgeon, the father of Charles. John Spurgeon went into business for several years, but he preached on weekends and eventually went into the pastorate full time. Serving in the independent churches of that time in England required some of the same conviction that Job Spurgeon had demonstrated in the seventeenth century. Religious freedom was more prevalent man a century before, but there were immense advantages to attachment to the Church of England.

Charles was the firstborn in the family and, apparently for financial reasons, lived the first few years of his life with his grandfather, James. “The Lord’s providential purpose can be perceived in this circumstance. Grandfather James ministered in the spirit of the great Puritan divines,” Lewis Drummond wrote in his biography, Charles Spurgeon, Prince of Preachers. “He represented the old Georgian-era Puritans in some of their best expressions. Charles had a happy childhood, and much molding of character took place in the grandparents’ home.”

He read the Bible there and undoubtedly heard his grandparents’ prayers. He also found his grandfather’s library of classic Puritan literature. He borrowed books on later visits after he resumed living with his parents. As parents or grandparents, we probably underestimate the impact of the books we put on our shelves. Children and grandchildren may seem to gravitate to VCRs or computers, but the best books, such as the Puritan classics, can have a life-changing impact on a Spurgeon, who then influences others for Christ’s kingdom.

The other important person in Spurgeon’s life was his mother, Eliza. She made the most of the time when the children were young, providing informal home-schooling in the early years. Charles, the first of 17 children, “looked back on her with deep affection and gratitude, and he tells of her reading the Scriptures to her children and pleading with them to be concerned about their souls,” Arnold Dallimore wrote in his biography of Spurgeon.

The proof of her effectiveness is seen not only in the life of Charles. His lesser-known brother, James, was his right-hand man as co-pastor of the Metropolitan Tabernacle for many years. James handled the administrative side of the huge ministry and was the key person, humanly speaking, in making his brother so successful. This loyal younger brother, by taking care of the administrative details of the exploding Metropolitan ministry, helped free Spurgeon up to exercise his best gifts in preaching and teaching.

The covenant promises in the ancestry of Charles Spurgeon did not stop at his death in 1892. Some physical and spiritual descendants picked up the baton he handed to them and passed it along successfully to more generations of believers, with a witness that continues today.

Spurgeon’s fraternal twin sons, Thomas and Charles, were pastors and preachers. Thomas, who had a successful preaching ministry in Australia, succeeded his father at the Metropolitan Tabernacle a couple of years after his father’s death and continued as pastor of the church until health forced his retirement in 1908. Even after retiring as pastor, he continued as president of the college and orphanage, eventually dying in 1917. The natural desire for him, or anyone in his place, might have been to remain in Australia, where he had an effective ministry of his own apart from his father’s shadow. But he was willing, because of the faith passed on to him, to take up the baton from his father and to pass it along to others. Craig Skinner, in Spurgeon & Son, details how Thomas Spurgeon was used by the Lord as part of the Spurgeon covenant succession, yet in ways very different from his famous father. Thomas’ own son, Harold Spurgeon, led the Irish Baptist College and was known for his skill in New Testament Greek.

The principle of covenant succession can be seen not just in Spurgeon’s family life but in his ministry, as well. The Metropolitan Tabernacle continues today as a church where the Gospel is preached. The book ministry that Spurgeon initiated also continues, and Metropolitan Tabernacle’s current pastor, Dr. Peter Masters, has been used in the rebuilding of the congregation he was first called to serve in 1970. Masters, an accomplished historian, has written two books, Men of Purpose and Men of Destiny, which trace the lives and characters of several Christians of the past two hundred years.

Spurgeon’s effective ministry of multiplication in the spirit of 2 Timothy 2:2 is one of the key reasons this church has remained so committed to the Bible and the historic Christian faith for more than a century since Spurgeon’s death, while many other churches, seminaries, and colleges have drifted toward secularism and indifference to their historic foundings. What Spurgeon had learned from Christ he taught to faithful men, who were able to teach others also, through his writings, the churches he helped start, and the college he began. When a great Christian leader goes on to be with the Lord, succession is always a challenge. Some leaders prepare for it better than others. But Spurgeon made it much easier because he worked so diligently at training others in what the Lord had taught him. No one person could replace him fully. But plenty of pastors trained indirectly through Spurgeon have carried on the spirit and heart of Spurgeon’s ministry for the past one hundred years. A History of Spurgeon’s Tabernacle, by Eric Hayden, indicates that several succeeding pastors after Thomas Spurgeon, and many of the assistants, had been trained in Spurgeon’s college.

As parents, what can we learn from this principle of covenant succession? Should we put pictures of Calvin and Spurgeon on our walls? Pictures probably have more impact on children than we realize. But the suggestion could miss the heart of the matter. Covenant succession should be a part of our prayers. Somewhere in these covenant families of Spurgeon’s line, someone must have prayed Deuteronomy 7:9 and pled for blessings on future generations. We must pray not only for our children, but for our grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and on down the line to a thousand generations.

Then look to the examples of the parents in these Spurgeon generations. They sought the Lord on their own and spent time with their children. They taught them to read, and read the Bible to them and with them. There was no magic formula, but they searched the Scriptures and came up with many ways of carrying out passages such as Deuteronomy 6:5–9, helping them memorize Scripture and learn the Shorter Catechism. Spurgeon’s own counsel to parents is still available in a book titled Spurgeon’s Sermons on Family and Home.

There are covenant promises that Christ still keeps fulfilling in families across generational lines. Yet each generation must claim and renew these covenants, and each generation shares responsibility for making a successful transition to the next generation of the truths of the Christian faith and the disciplines that keep the spiritual fires burning.