Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

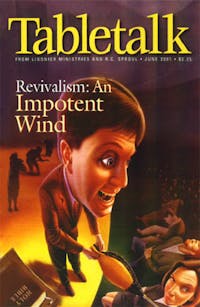

“Heal,” he commanded, putting his hands on the woman’s forehead and scrunching up his face in prayer. “HEAL!” And, glory be, she got up from her Wheelchair and walked across the stage.

One of my earliest and greatest TV experiences growing up in a small town near Tulsa, Okla., in the 1950s and 1960s was watching the Oral Roberts show. The music, which even a 10-year-old recognized as corny, and the sermon, full of sound and fury, were just build-ups to the healings. I couldn’t help but wonder each week whether the leg would get untwisted and the backache would go away this time, but sure enough they did. In flickering, grainy black and white, I was watching a man perform miracles. It made for great television.

Roberts was big in rural Oklahoma in those days and kept getting bigger and bigger. He built a college, named after himself, with a design straight out of The Jetsons. Then, following a vision of Jesus, he built a gigantic hospital. By then I was old enough to wonder why he needed to build a hospital if he really could heal the sick. Why couldn’t he just walk through the wards, lay his hands on people, say “Heal … HEAL!” and send them home?

Our pastors didn’t care much for him. They not only questioned his theology, they got irked at the way people sent him money that otherwise might have gone to hard-pressed local congregations. But they could hardly compete with a man of God who could heal the sick.

Long before television, itinerant evangelists went through the South and West, putting on “revivals.” They were not just preachers, they were showmen, mixing the Gospel with signs, wonders, and their own personalities, which they projected with the skill of actors.

The revivals back then were distinct from the churches. They were travelling attractions, like circuses and medicine shows. They were primarily evangelistic efforts, geared for attracting and converting non-believers. Though Christians could not resist going to revivals, their faith was mainly nourished in the churches, which were part of their everyday lives, places to worship and feed on God’s Word. Their pastors may not have been spectacular performers like the itinerant evangelists, but they shepherded their people through the good times and bad times—births, baptisms, weddings, and funerals—and were always there for them, ministering with counsel, admonition, and the comfort of Christ’s forgiveness.

Eventually, though, revivalism moved into the churches. Traditional worship services, with their rich hymns and reverent liturgies, were dismantled, to be replaced by hot gospel music and emotional frenzies. When this happened, the role of the pastor changed as well. It was not his office, or his ordinary ministrations with the Word and the sacraments, that constituted his leadership. Rather, it was the force of his personality. Thus, revivalism gave the church the cult of personality as it never had known it before.

The preacher was the man with the gift. Sometimes this simply meant that he was a good, entertaining preacher with an attractive personality that made people flock to his church. But sometimes his gifts were more dramatic. He heard the Lord speak to him. He claimed to have visions. He had special powers, with the Holy Ghost being strong in him, to work miracles and to fire up his congregation.

People once chose to go to a particular church because it embodied what they had come to believe. They grew up Presbyterian, Lutheran, or Baptist—came to faith in that church—and when they moved to other towns, they sought out and attended the church of their convictions. But now they started choosing a church because of the preacher. Someone might be attracted by anything from a minister’s friendliness to his spiritual magnetism, but the particular theology of the church—its teachings and its doctrinal identity—hardly entered at all into the decision of where to worship.

Certainly, having a good pastor is an important draw for any church. And certainly there is nothing wrong with looking to particular teachers or theologians for spiritual sustenance. There is a clear difference, though, between following authentic Christian leaders and joining a personality cult. True Christian leaders point not to themselves but to Christ. The source of their knowledge, authority, and ministry is not themselves but God’s Word. They say of Christ, as did John the Baptist, “ ‘He must increase, but I must decrease’ ” (John 3:30).

In personality cults, by contrast, the leader is the fount of revelation. People follow him for himself. Without the leader, the group—being based on nothing else—falls apart.

A congregation operating on the assumptions of “charismatic leadership” places a terrible burden on its pastor. The minister can be pressured into playing the role of supernatural dynamo. When he isn’t able to pull it off, he sometimes has to fake it. To put it mildly, this can exact a heavy toll on a minister’s sincerity and his faith. Inside, he is another struggling Christian, but he must put on the front of the Holy Shaman. Sometimes, he is torn by guilt at what he is doing; sometimes he just becomes cynical or falls into a twisted double life, such as we have witnessed in the moral failures that have led to the downfall of many celebrity ministries.

Worse, though, is when the leader believes in his own supernatural powers, his own inerrancy, a notion that can lead only to spiritual catastrophe, both for himself and for the followers he both tyrannizes and leads astray.

Intrinsically connected to the cult of personality is theological distortion. If the leader is a source of revelation—if God supposedly speaks directly to him, whether through a voice, visions, or direct illumination—it has to follow that what he says must command divine authority. If Jesus did indeed appear to Oral Roberts in a vision, then Christians were duty-bound to send him all the money he needed. He was a conduit for God’s Word; therefore, what he said had the same authority as the Bible.

The Reformers were wise when they put the “sola” into sola Scriptura. They not only insisted on the authority of the Bible—which Catholics and today’s personality cultists also tend to acknowledge—they insisted that the Bible alone was to be the authority. They recognized no extra-Biblical revelations, whether from the pope or from other individuals claiming to speak for God. The Reformers struggled not only against Roman Catholics but against the personality cultists of their day, the “enthusiasts,” so called because they trusted “the God within” (from the Greek en and theos), as opposed to the God who, though indwelling, is radically beyond the self.

Martin Luther said that the papacy and the enthusiasts were ultimately the same: Both taught that God reveals Himself through human beings, apart from His written Word. Actually, he went on, the enthusiasts were probably worse, since the Catholics had only one pope, while the enthusiasts, in effect, had legions of popes.

In addition to the Bible, another corrective to the cult of personality is a strong view of the pastorate. The pastor’s authority and his effectiveness do not inhere in his own personality, “leadership gifts,” or unique powers. Rather, they come from his calling. God does work through human beings—bringing new life into the world through parents, giving us our daily bread through farmers, protecting us through the civil authorities—and He proclaims the Gospel and brings people to faith through the vocations He establishes in the church. Thus, people in a pastor’s congregation need to recognize him as a fellow redeemed sinner, but also as the holder of an office in which God promises to work.

For his part, the person called to the pastorate needs to recognize that he has been placed there to serve and not to be served (Luke 22:25–27), that his message is not his own but is in the Bible he carries in his hands. It is, in fact, a liberating feeling when a pastor realizes that his ministry resides not in his own sweet self but in faithfully administering the Word and the sacraments.

When I was 10, I liked to watch Oral Roberts doing miracles. This childish love of the spectacular, the desire to see something supernatural actually happening and to get caught up in the emotions of it all, was to walk by sight and not by faith. The desire for the extraordinary can blind a person to the richness of the ordinary.

Luther spoke of how God “hides Himself” in places we do not expect. We human beings prefer religions of “glory,” featuring spectacular special effects, victory upon victory, and emotional, mystical self-fulfillment. But Christ did not come in that fashion. He did not glorify Himself but came as an outcast child and saved us by dying on a Cross. And just as God in His glory hid Himself in the Cross, He hides Himself in a leather-bound book, in ordinary human vocations, in the day-to-day, frequently unspectacular life of the church, and in the sometimes fumbling words of a sometimes insecure man in a pulpit. To expect something else, to look for God in unusual experiences or in a cult of personality, is to miss where God promises to be.