Request your free, three-month trial to Tabletalk magazine. You’ll receive the print issue monthly and gain immediate digital access to decades of archives. This trial is risk-free. No credit card required.

Try Tabletalk NowAlready receive Tabletalk magazine every month?

Verify your email address to gain unlimited access.

Most all of us, at one time or another, have found ourselves embarrassed by God. He who has all perfections perfectly doesn’t always fit into our scheme of things. He doesn’t always do things the way we who are altogether imperfect think they should be done. We weep with Aaron as God destroys two of his sons for merely toying with strange fire. We sympathize with Job’s wife, cheering her on as she nags her husband into blasphemy, even though we have been permitted to eavesdrop on the heavenly conversation between the devil and God. Many of us shed a tear for the soldiers of Pharaoh as we watch the Red Sea crash down upon them. We nurse a secret grudge as we watch God strike Uzzah for touching the ark of the covenant.

Nothing, however, assaults our sensibilities more than the execution of God’s holy war against the people of Canaan. We tell our children about Joshua’s march around Jericho. We don’t tell them that every person in the city—men, women, and children, with the exception of Rahab’s family—was put to death. Joshua at Jericho made Gen. William T. Sherman’s march to the sea look like a picnic.

In Judges, the sword of the Lord turns on the children of Israel. As the Benjamites shelter and defend the men of Gibeah (Ch. 20), they become as the Canaanites, and their city and all within it is burned to heaven. God judges swiftly and severely in this time of conquest.

Our temptation is to focus our attention on the New Testament, particularly the gospels. There we see no mass executions by God. Rather, we see He who would not harm a bruised reed. We find a kinder, gentler vision of the Almighty in the tender grace of Jesus. We find not a mile-long list of rules covering how we are to wash, what we may and may not eat, and just how the stoning of the unfaithful is supposed to look. Instead, we find Jesus preaching to the multitudes, casting aside the “You have heard that it was saids” and giving in their place an ethic of love. There we seem to hear a message that we be not mighty warriors like Joshua or Samson but instead be poor in spirit. We are to be merciful peacemakers. We are to be pure in heart. We summarize the message of Joshua as this: We are to be warmongers, mean-spirited, and bloodthirsty. Jesus seems to tell us we not only may, but must, be nice.

If we succeed, He tells us, we shall have the kingdom of heaven. If we will stop beating our chests like crazed warriors and instead mourn, we will be comforted. If we will hunger and thirst after righteousness, we will have our desires met. If we will stop destroying the wicked and instead show them mercy, we will receive mercy. If we will keep a pure heart, we will see God. If we will promise to learn war no more and become peacemakers instead, we will be called the sons of God. And if our unconditional love is rejected by men and we are persecuted, again, we will inherit the kingdom of heaven.

I skipped one. Jesus also calls us to be meek, hardly the picture of Joshua as he leads his troops into battle. But if we are meek, what do we receive? The meek shall inherit the earth. Here is perhaps the biggest change and the greatest similarity. The similarity is that, like the children of Israel, we have a promise of a promised land. The difference is that our promise is not limited to a small strip of land in the Middle East. We’re going to inherit the entire world. All of it has been promised to us.

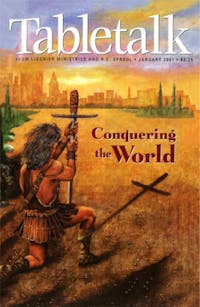

Of course, this, too, has changed: The weapons of our warfare are not carnal. The only sword we carry into battle is the sword of the Word, the Gospel of the kingdom. But this sword analogy is slightly limiting. We are not merely cutting down the bodies of pagans; we are, in the Holy Spirit, ripping their hearts of stone out of their chests and replacing them with hearts of flesh. We are not merely removing the pagans—we are remaking them, just as we have been remade.

What hasn’t changed is that we are at war. It is a constant. The war did not begin with the conquest of Canaan. And it did not end in 1967. It began in Genesis 3, when God promised that He would put enmity between the seed of the woman and the seed of the serpent. That was the declaration of war and the institution of God’s regenerative draft—He put the enmity there, moving the woman and her seed from the forces of darkness to the forces of light, enlisting them with His effectual call. And the war will continue until our Captain, the true Joshua, has put all things under His feet (1 Cor. 15:24).

That is the greatest change. We are no longer fighting in ourselves. If we were, there would be nothing but defeat. But in Christ, we are poor in spirit but rich in the Spirit, who indwells us. In Christ we mourn. And in Christ we rejoice, for He has overcome the world. In Christ we are meek, and in His meekness we inherit His reward, the entire world. In Christ we are bold and strong, for He is with us wherever we go. And when that great and final day comes, in Christ we will be pure in heart, and so we shall see God.

Today He sees us. We live our lives in this context of warfare, coram Deo, before the face of God. He is watching us, guiding us, directing us. And so we are called to be more than conquerors, greater than Joshua. We are not looking for a place at the world’s table. We are not looking for recognition of our value in the grand scheme of things. We are not looking to merely keep the world from crashing down around us. We are fighting for our God-given right to the world. We are called to total world conquest beneath His gaze, under His authority, and unto His glory. And we, in Him, shall have it, for the King has come, and He will come again.